Changing Tides in Cambridge Industry

By Beth Folsom, 2022

In an article written in January of 1912, a reporter for the Cambridge Chronicle extolled the city’s place as a leading center of industry in Massachusetts, not just in the overall amount of manufacturing that took place in the city, but also the diversification of industrial production. Cambridge’s factories, he argued, were varied enough that a disaster – either natural or man-made – in one industry would not shut down the city’s economy. Citing the example of Lawrence, which had recently been paralyzed by a strike in the textile mills, the author emphasized the fact that Cambridge’s myriad of different industries would preclude such a shutdown, as “the employees of our great publishing houses might strike, but this would not disturb the Blake & Knowles pump works. There might be a labor disturbance in the plant of the Boston Woven Hose company, but the production of pianos and organs would go on apace.”

By the early twentieth century, Cambridge was an industrial center with a broad array of factories, many of them staffed by workers from other parts of the country and the world. What impact did both domestic and international migration have on the creation, development, and sustaining of the city’s industrial sector? What similarities existed in the ways various ethnic and racial groups were represented in Cambridge industry, and in what ways did they differ? How did newly-arrived migrants use their work in industry to climb the socioeconomic ladder, and how did factory owners and managers attempt to use workers’ ethnicities to limit their mobility and organization?

One of the industries for which Cambridge is best known is candy-making – at its peak in the mid-twentieth century, the city boasted 66 different candy companies, including Squirrel Brand, Daggetts, and NECCO. The candy industry began in the 1760s, when an Irish immigrant named John Hannon built a chocolate mill on the Neponset River in Dorchester. The introduction of the steam engine in the 1840s created a boom in the candy market, and many companies moved from Boston to Cambridge, where land was cheaper. Over the course of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, wealthy Cambridge families maintained ties to the sugar plantations of the Caribbean; many of the city’s white elites not only enslaved people of African descent on their estates in and around Cambridge, but they also owned and/or profited from the enslavement of vast numbers of people in Jamaica, Antigua, and other islands. The proceeds from this enslaved labor helped to fund both private residences and public institutions throughout the city, and continuing economic ties to the Caribbean sugar economy greatly contributed to the rise of Cambridge as a candy-making hub.

During its first eight decades, the candy industry, like so many others in the Northeast, was comprised mostly of British and German immigrants, many of whom had worked in food production in their home countries. Beginning in the mid-1800s, these workers largely transitioned to other industries, and the legions of Irish immigrants fleeing from the Potato Famine took their place. A generation later, at the end of the nineteenth century, the Irish were in turn replaced by new arrivals from Italy, Portugal, Lithuania, and other parts of Eastern and Southern Europe – as well as Barbadians and other Caribbean immigrants seeking to escape from their islands’ collapsing economies. Beginning in the early twentieth century, these immigrants from abroad were joined by Black migrants leaving the South to find better socioeconomic and political conditions in the North, including the racially-integrated schools of Cambridge.

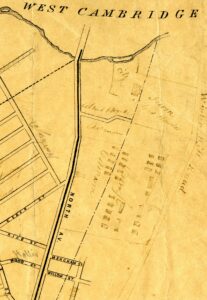

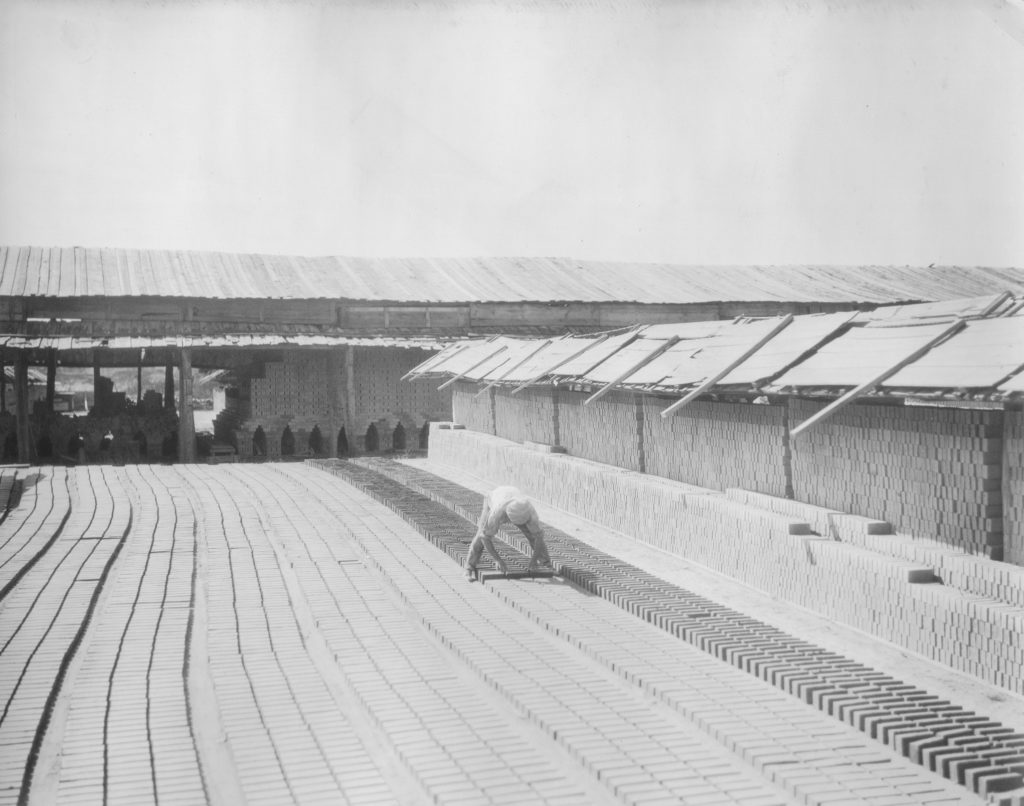

The changing demographics of the candy industry can also be seen in other sectors of the city’s economy, as well as the ways in which racial and ethnic divisions fueled antagonism between groups and kept workers from effectively organizing for improvements in working conditions. The abundant clay pits of North Cambridge had long been used for pottery and small-scale building projects by both Indigenous communities and the English colonists who lived in the area during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution had led to a demand for nonflammable building materials for factories and workers’ houses, and the brickyards springing up throughout North Cambridge prospered as they met that demand; by 1858, the neighborhood’s factories were producing approximately 187,000 bricks per day. Beginning in the 1890s and continuing through World War I, financial turmoil made it impossible for many of the smaller companies to survive and led to a consolidation of most of the area’s brick industry under the auspices of the New England Brisk Company. But brick-making continued to flourish, with its workforce following much of the same demographic shifts seen in the candy industry.

From the 1840s to the 1870s, the Irish dominated the brick industry so prominently that the neighborhood around the brickyards was known as “Dublin” or “New Ireland.” By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the descendants of these earlier Irish immigrants had largely moved into other, less strenuous and better-paying jobs, and more recent arrivals from Quebec took their place.

As is often the case when one ethnic or racial group moves up the socioeconomic ladder, the Irish immigrants and their children and grandchildren did not embrace the incoming French Canadians; despite the fact that they shared a common Roman Catholic heritage, the Irish refused to let the Canadians worship in their churches, forcing them to create their own parish at the turn of the century. This trend of yesterday’s newcomers becoming “gatekeepers” to those who come after them has been repeated in many different industries within and beyond Cambridge.

The soap industry that flourished in Cambridgeport in the mid-nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century also reflects the changing demographics of migrant groups to the city during that time. In the 1850s, Cambridge companies like Reardon’s and Alden Speare’s Sons produced primarily candles in their local factories. But by the late 1800s, as candles gave way to gaslight, these companies began to focus more on lamp oil and soap. Lever Brothers, which had long been successful in England, entered the U.S. market when its Cambridge factory opened in the 1890s and soon came to dominate the local soap industry.

The area of Cambridgeport came to be known as “Greasy Village” because, when the carts carrying supplies to the soap factories turned too quickly on the rutted streets, pieces of bones and lard would fall off, leading to a distinct smell and a greasy film that residents complained would linger long after the debris was removed.

As was the case near the brickyards of North Cambridge, the area around the soap factories in Cambridgeport was home to many of the workers who labored there, including Irish in the 1850s and 1860s, French Canadians in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and Italians, Portuguese and Poles during the first half of the twentieth century. This last wave of immigrants from abroad were joined by Black Southerners heading north as part of the Great Migration.

As one demographic group began to move into better-paying employment, the next group would take its place – often without the support of their predecessors. Across industries, owners and factory managers took advantage of the fact that their workers spoke different languages and couldn’t easily communicate with one another to coordinate strikes or other labor actions. And those workers who had been in Cambridge for a generation or more often held onto what small measure of assimilation and “respectability” they had managed to attain, refusing to act in solidarity with those who had come after them.

As waves of immigrants arrived from all corners of the globe in the twentieth century, Cambridge as a whole – and Central Square in particular – expanded its culinary horizons to include the cuisines of these new Cantabrigians who had come to work, study and live in an increasingly diverse city. As restauranteurs diversified to meet the demand for a broader array of foods, many Cambridge residents also expanded their palates, learning about both the cuisine and the culture of their immigrant neighbors.

At The Middle East, traditional Lebanese food has both helped remind immigrant diners of the cuisine they left behind and also introduced many Cantabrigians to a new kind of ethnic cuisine. Food has been a natural convener of Tibetans in exile, and the establishment of Rangzen Tibetan Place and other Tibetan restaurants in the area has allowed immigrants to maintain ties to their ethnic heritage while also building community ties between Tibetans and Cambridge residents of other backgrounds. And the combination of food and music at La Fábrica Central makes it a gathering place for Dominicans from across the region to come together, as well as for non-Dominicans to experience Latin American/Caribbean cuisine. Employment in the restaurant sector, whether as chefs, waitstaff, or owners, has allowed new immigrants an entry point into Cambridge industry and a connection to their ethnic communities, and the proliferation of restaurants from all corners of the globe highlights the increasingly diverse nature of the city’s population.

Candy, soap, bricks and food are just a few of the many industries that have called Cambridge home over the past two centuries. Here are some resources for learning more about the rich heritage of ethnicity and labor in the city:

Self-Guided Tour: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge

Self-Guided Tour: Caribbean Community in the Port

Self-Guided Tour: Clay, Bricks, Dump, Park: A Tour of North Cambridge

Global Boston: A Portal to the Region’s Immigrant Past and Present (Courtesy of Boston College)