Self-Guided Tour: The History of Candy Making in Cambridge

By Natalie Moravek, Intern

In 1946, sixty-six candy manufacturing companies were listed in the phone book. The candy industry in the area began in 1765, on the banks of the Neponset River in Dorchester, when an Irish immigrant named John Hannon established a chocolate mill. The large and populated city made an ideal setting for a new industry to start up, and soon candy companies began springing up in Boston as roadside operations. With the introduction of the steam engine, and a lozenge-cutting machine in 1847, many of those same businesses expanded their reach into Cambridge. Land was cheaper in Cambridge, and the city became a major industrial center. At its height, Cambridge was the second largest industrial production city in Massachusetts and candy was one of its main businesses. While most of the candy factories are gone, one remains and many of the buildings are still standing.

Overview and History

The tour begins in Kendall Square, and with the high-tech firms and pharmaceutical companies that now dominate the landscape, it’s hard to image that fifty years ago in Cambridge, candy was king. Main Street was once affectionately called Confectioner’s Row, and the companies here made products that are still known and loved today: Junior Mints, Charleston Chews, Sugar Daddies, and NECCO wafers.

The area’s confectionery past begins way back in 1765 when an Irish immigrant named John Hannon established America’s first chocolate mill on the banks of the Neponset River in Dorchester. Soon after, candy companies started as roadside operations: the proximity of the chocolate mill, plus nearby sugar refineries and a large city population made the area ideal for the new industry. Soon, companies Royal, Cole, Haviland and Liberty made chocolate in Boston, and to the east in Charlestown was the boxed-chocolate giant Schrafft’s.

Then, with the introduction of the steam engine, local companies began producing the first candy-making machines. In 1847, Oliver R. Chase made a lozenge cutting machine and began to produce the wafers later known as NECCOs. Successful confectioners soon outgrew their Boston factories and decided to expand production in Cambridge, where more land could be bought for less money.

For the next 100 years, Cambridge was a major industrial center and candy making was one of its largest industries. In 1910 there were sixteen confectionery manufacturers listed in the city, by 1920 the number was thirty, and by 1930 there were more than forty. At its peak in 1946, there were sixty-six candy manufacturing companies listed in the city’s directory.

The beginning of the end for Cambridge candy came with the rise of the big national candy conglomerates, namely Hershey’s, Nestle, and Mars. These companies understood that distribution had changed. You had to get involved with the big chains, and you had to be more centrally located where you could ship everywhere. Success in the industry became less about who was producing the best candy and more about who could get to market first. Independent confectioners were hard pressed to match the conglomerates’ distribution levels, national marketing efforts, and slotting fees, which is the price companies pay to have their candies front and center of the register at the grocery store.

This tour will touch upon what’s left of Cambridge’s candy legacy, and will also mention other sweets, like cookies and ice cream, which also have histories here.

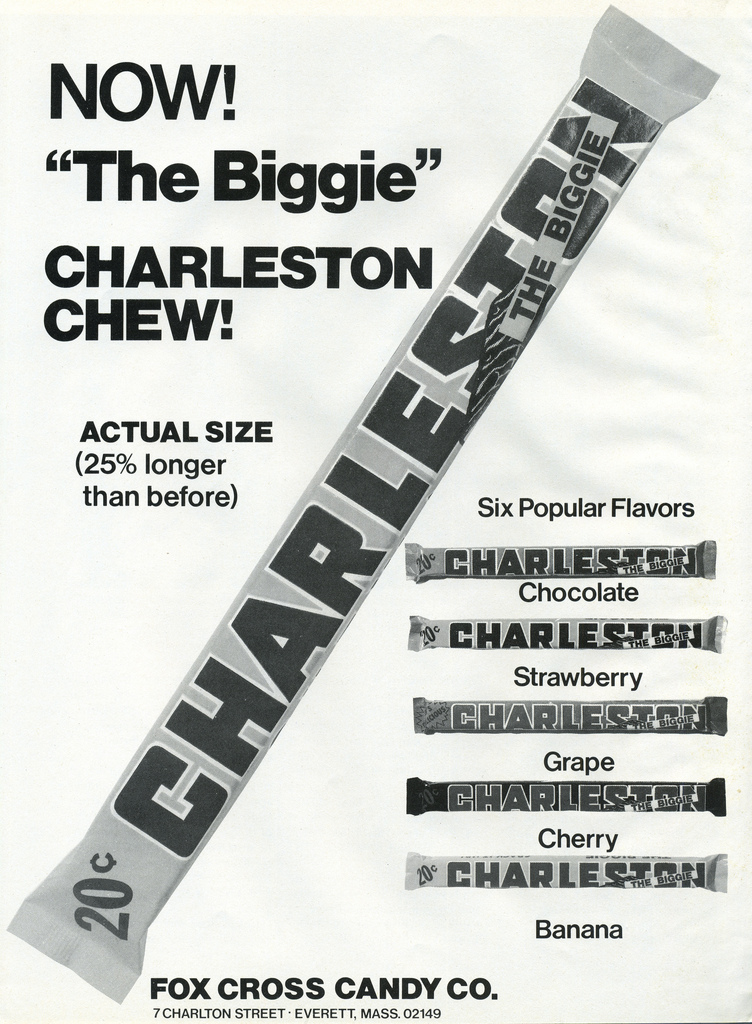

Fox Cross Company

292 Main Street (1920-1980)

The first stop is the Fox Cross company, best known for making the Charleston Chew.

The start of this company is an unusual one. Donley Cross was a Shakespearean stage actor in San Francisco in the early 1900s. During one performance, Cross fell of the stage, injuring his back. The injury ended Cross’s acting career forcing him to look for other work. He chose candy. With his friend Charlie Fox, Cross opened the Fox-Cross company in 1920 with the launch of a candy bar called the Nu Chu.

The candy bar that made them famous wasn’t launched until 1922 when they took vanilla flavored nougat, covered it with milk chocolate, and called it the Charleston Chew, trying to capitalize on the popular dance craze at the time.

Ownership of the company changed hands many times and there is actually no clear history as to why production ended up here in Cambridge. The earliest they appear in the city directory is 1931 when they were listed at 26 Landsdowne street right by the old NECCO plant. The company moved to this location in 1946.

A new wave for Fox-Cross really started when Nathan Sloane bought the company in 1957. Sloane himself has a storied history in candy. He began his career in 1925 at age sixteen when he started distributing penny candy from manufacturers to family-owned shops. Sloane eventually bought Kendall Confectionery, a distributor in Kendall Square, and American Nut and Chocolate (a nut roaster in South Boston), but it was always his dream to manufacture a successful candy bar.

Although the Charleston Chew was already well known, Sloane did much to bolster the brand. He eventually moved the business to a larger factory in Everett, automated production, and built the brand name through advertising. Under Sloan, Charleston Chews were one of the first candies to suggest that customers use their home refrigerators to freeze the product. And now Chew lovers swear by the “Charleston Crack” which is freezing them and then smacking them on a hard surface to create bite-size pieces. Sloan never changed the original Charleston Chew recipe, but he did introduce new flavors like chocolate and strawberry. He doubled the size of the production line before selling the company in 1980.

By 1980, national candy conglomerates, chiefly Hershey’s and Mars/M&M had taken over the candy scene and Fox Cross suffered a fate typical in the industry. After Sloane sold the company to Nabisco in 1980, Nabisco sold the business to the drug firm Warner Lambert, who sold it in 1993 to Tootsie Roll Industries. Tootsie Roll also owns the remains of another storied local outfit, the James O. Welch Company, best known as the maker of Junior Mints, Sugar Daddies and Sugar Babies.

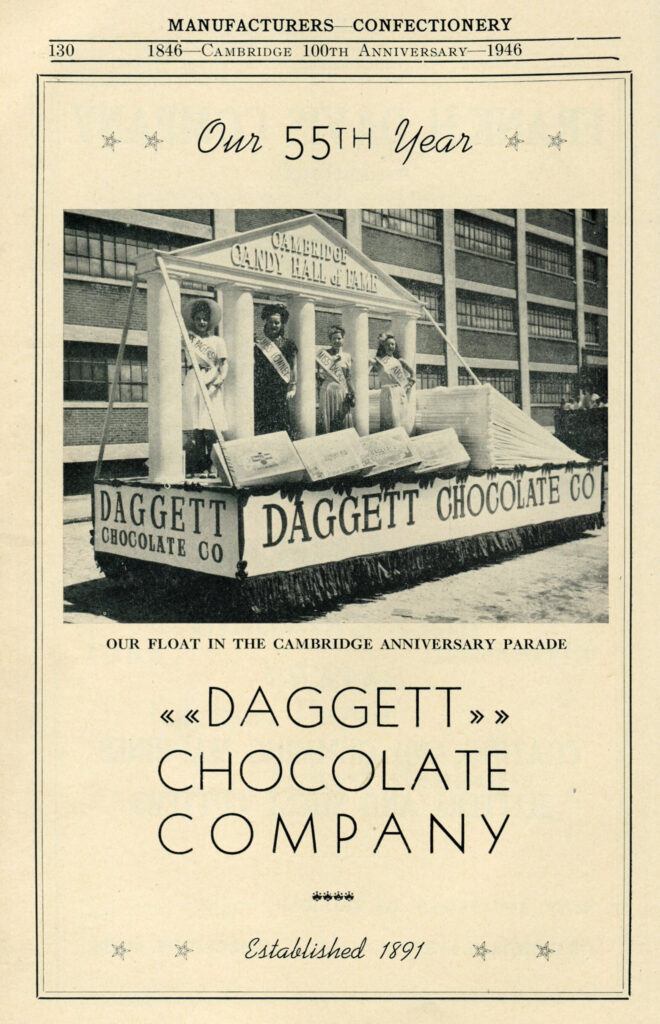

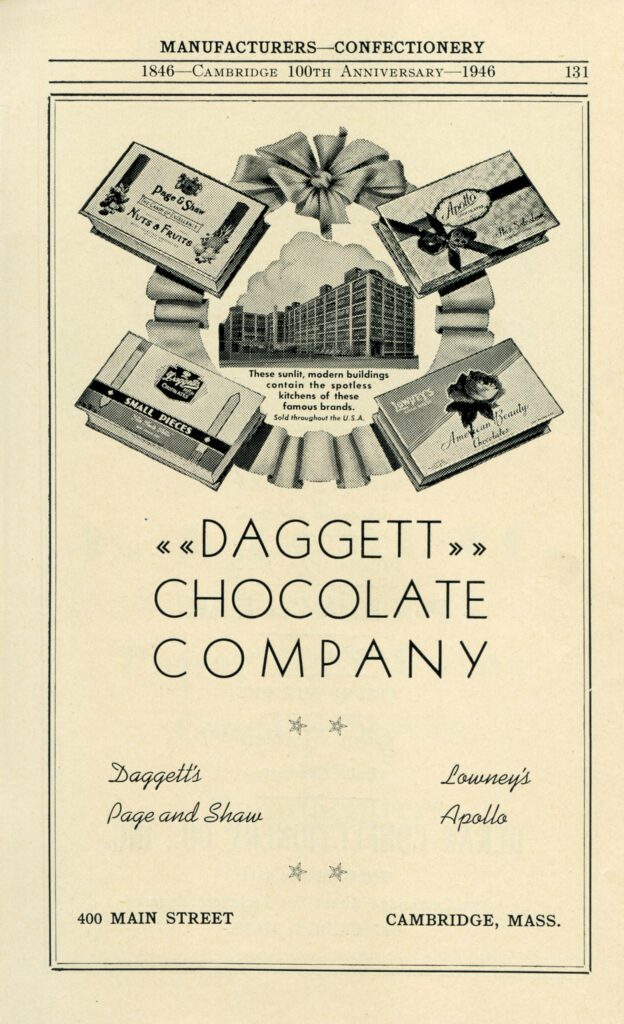

Daggett Chocolate

400 Main Street (1892-1960s)

By the 1940s, Cambridge candy companies were eventually consolidated into two: Daggett Chocolates and New England Confectionary Company, or NECCO. While NECCO has survived and continues to make a large line of products, fewer people remember Daggett’s.

Fred L. Daggett opened business in 1892 in Boston and maintained multiple factories around the city. In 1925, desiring to concentrate production and distribution and to secure more manufacturing area, F.L. Daggett built his Cambridge plant, a trend popular with other confectioners seeking more centralized space.

Daggett Chocolates became a huge company producing more than 40 brands of chocolates. It took up an entire city block in Kendall Square, where it not only produced candy, but also the boxes the candy came in. The factory had three separate unions: one for the confectionery workers, one for the box makers, and one for the printers.

The company also had a special fruit department. The Daggetts owned and operated a strawberry plant in Virginia where strawberries were preserved in sugar to make fillings for their chocolates. Through this venture, the Daggetts also had an impact on ice cream and soda fountain business in the area. They supplied thousands of gallons of syrups and crushed fruits to druggists and ice cream manufacturers. In this way, candy and ice cream kind of became connected. In later years, Boston was the first place to see candy actually being mixed in to ice cream.

In the late 1950s, Fred L. Daggett, the founder, died. The company survived for a few years, but closed in the early 1960s. The equipment and the recipes were sold to NECCO and the building was sold to MIT. Daggett’s end came at the start of a tumultuous time for the chocolate industry. A good example is Schrafft’s in Charlestown (Its building, with the giant clock tower and red sign visible from I-93 is now an office complex). The name Schrafft’s had become synonymous with boxed chocolates. But by the 1950s, boxed chocolates were being squeezed off the shelves by candy bars, and in scrambling to retain market share, boxed chocolate companies were conglomerating. Schrafft’s also failed to keep up with distribution practices. The rest of the market began selling directly to chain stores, and they continued to use distributors. The company went into major debt and closed in the mid 80s after years of struggle.

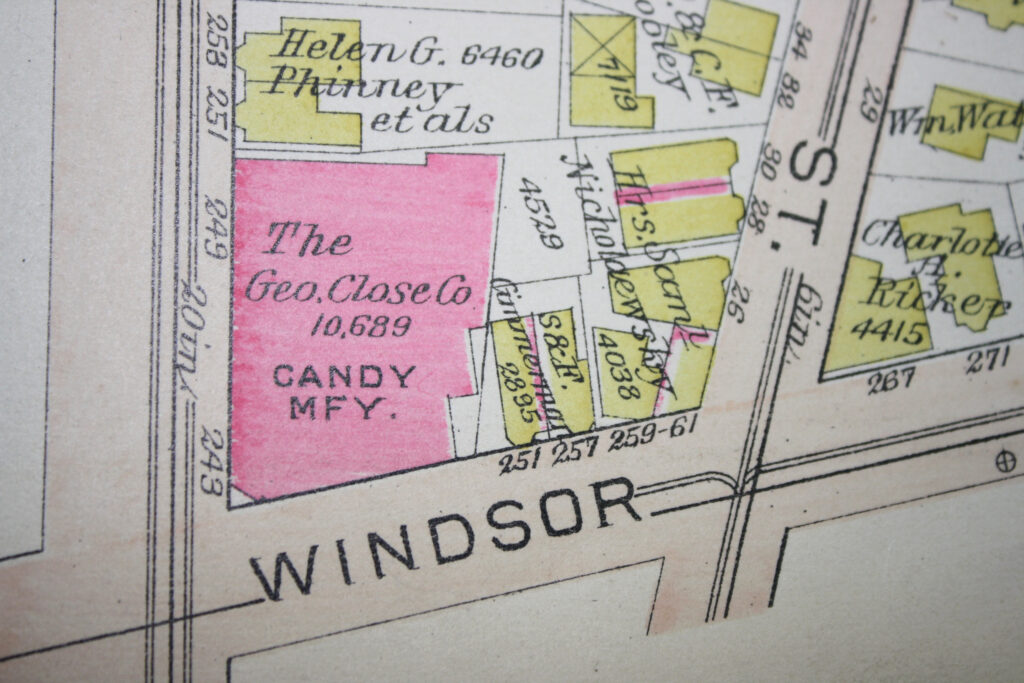

George Close Company

243 Broadway (1861-1930s)

George Close started his company in 1861, and after a fire destroyed the first factory, the company moved here in 1879.

Though known in its day for chocolates, suckers, lemon drops, sponge cakes, and butter balls, today the George Close name is most recognized by baseball card collectors. In a unique advertising ploy, in 1911 the company produced a 30-card baseball set that included players like Cy Young and Ty Cobb. The back of the cards were overprinted with ads for the George Close Company. Overprinting is a term commonly used to refer to the rare practice of a company taking cards already printed (in some cases even issued by another manufacturer) and adding advertising, in the form of printing or an ink stamp, to allow the cards to function as its own advertising vehicle at modest cost. There are ten known different back overprints by the George Close Company and they feature slogans like “Home Run! For Close’s Butter Balls” and “You’re Safe! If You Eat Close’s Chocolates”.

The company did not survive the depression, but at least the baseball cards are still of value. A mint condition Cy Young card with a George Close overprint is valued as high as $25,000.

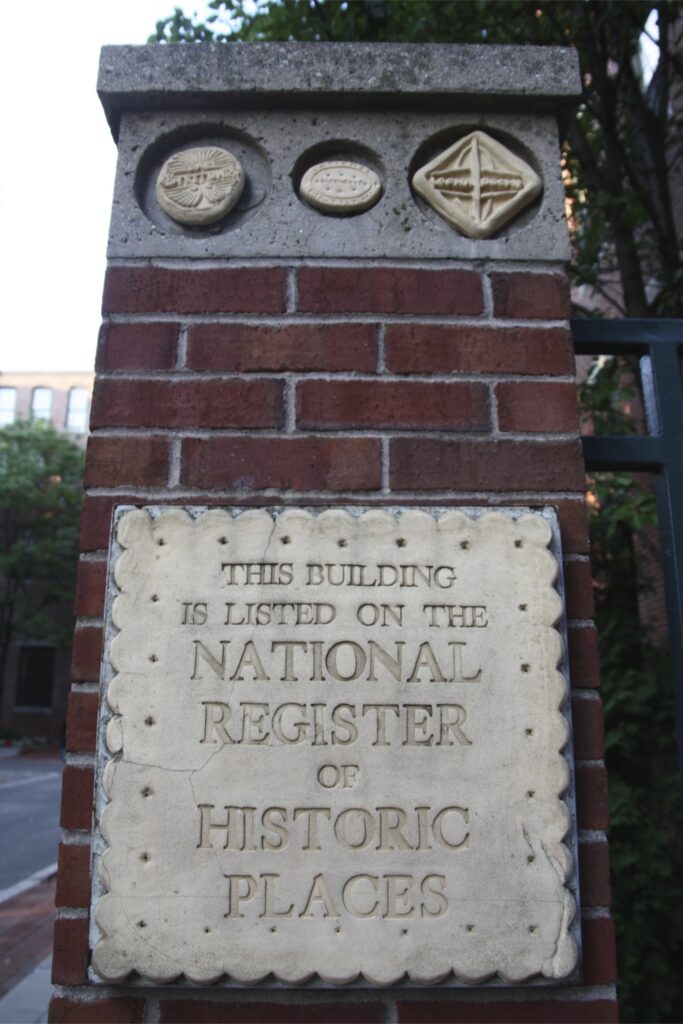

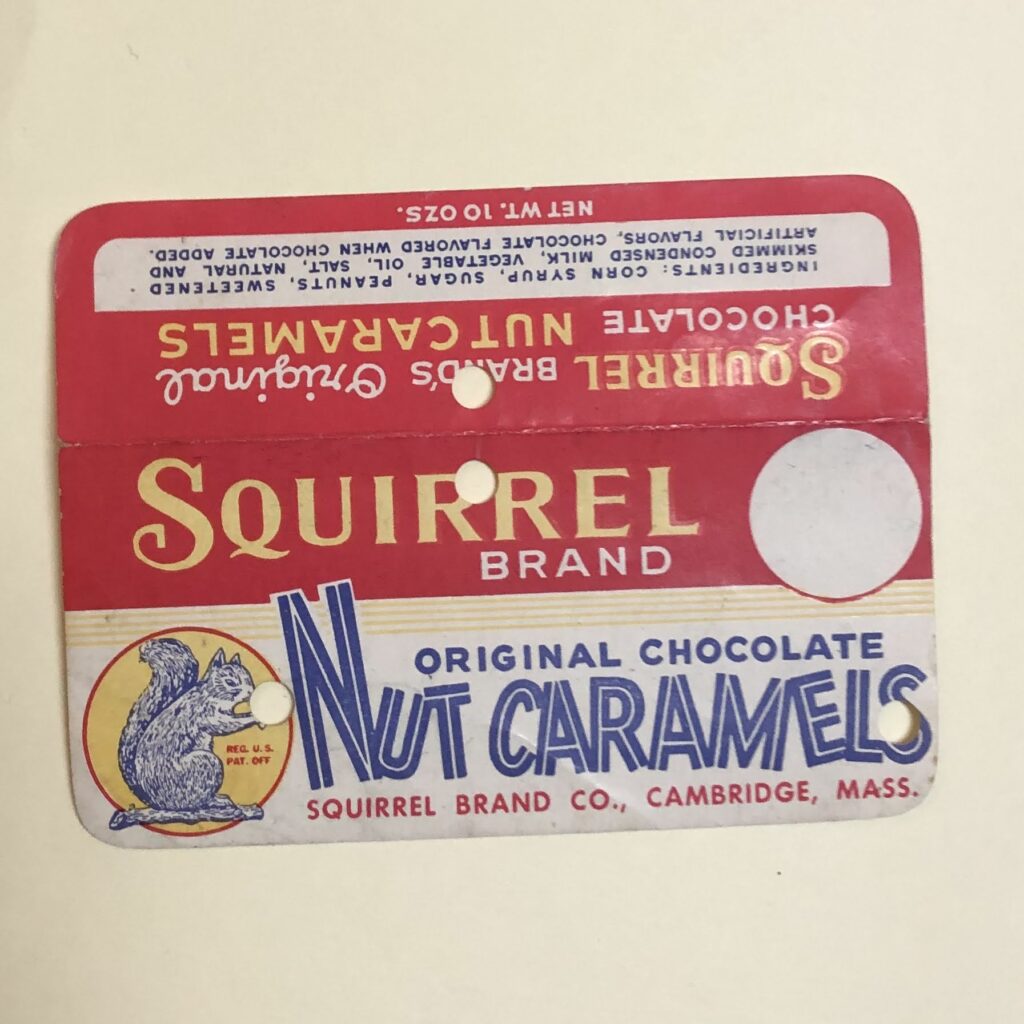

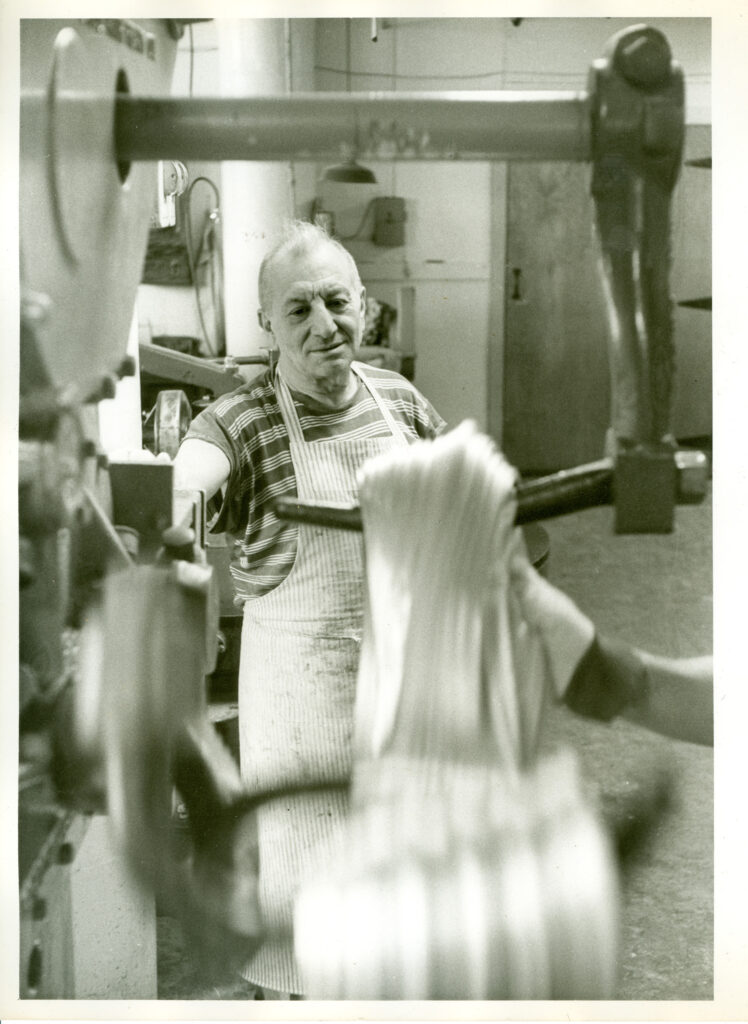

Squirrel Brand Nuts

12 Boardman Street (1890-1999)

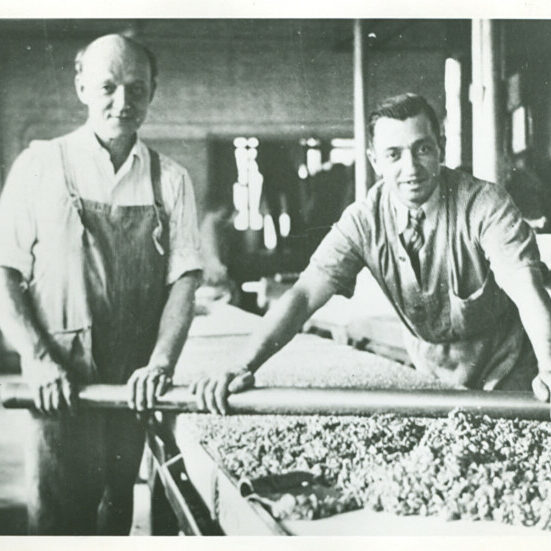

The Squirrel brand dates back to 1890 when it started as the Austin T. Merrill Company in Roxbury. Incorporated in 1899 as the newly named Squirrel Brands Salted Nut Company, the company’s ownership changed and two long-time employees, Perley G. Gerrish and Fred S. Green, began to run the business. As the company grew, it moved from its Boston location to Cambridge in 1903 and then to this building in 1915.

The company was here in Cambridge from 1915 to 1999. Originally, Perley Gerrish would sell his mixed nut varieties from store to store throughout the area by means of horse and wagon. Here, Squirrel Brand produced nuts that were carried by Admiral Richard Byrd, who lead the first expedition to reach the South Pole by air. The nuts were also shipped all over the world during WWII.

From salting to roasting peanuts to chewy taffies and nougats, Squirrel Nut Company developed a loyal customer base. Some of their brands over the years have included Butter Chews, Nut Chews, and Nut Yippees. Their popular flagship product was the “Squirrel Nut Zipper,” a vanilla, caramel, and nut taffy that supposedly was named after an illegal drink during Prohibition. The candy was always regionally popular, but it made more of a national comeback during the 1990s when a retro swing band named themselves the Squirrel Nut Zippers and gave out the candy at their performances. Watch our interview with Squirrel Nut Zippers’ frontman Jimbo Mathus here.

When Hollis Gerrish, the son of the founder, died in1997, he left instructions for the company to be sold. In 1999, Squirrel Brand Company was purchased by Southern Style Nuts and the operation was moved to Texas. Its leaving marked the departure of the city’s last major independent candy manufacturer. History Cambridge holds the Hollis G. Gerrish Papers, 1865-2002 in our collection. View photos from the collection below:

In 2004, NECCO picked up the license from Southern Nut Company to manufacture squirrel candy brands. Squirrel Nut Zippers and Caramel Chews returned home to Massachusetts, and is just one of NECCOs more recent acquisitions that has helped turned them into an anomaly of the candy industry, and a sort of retro outfitter of sweets.

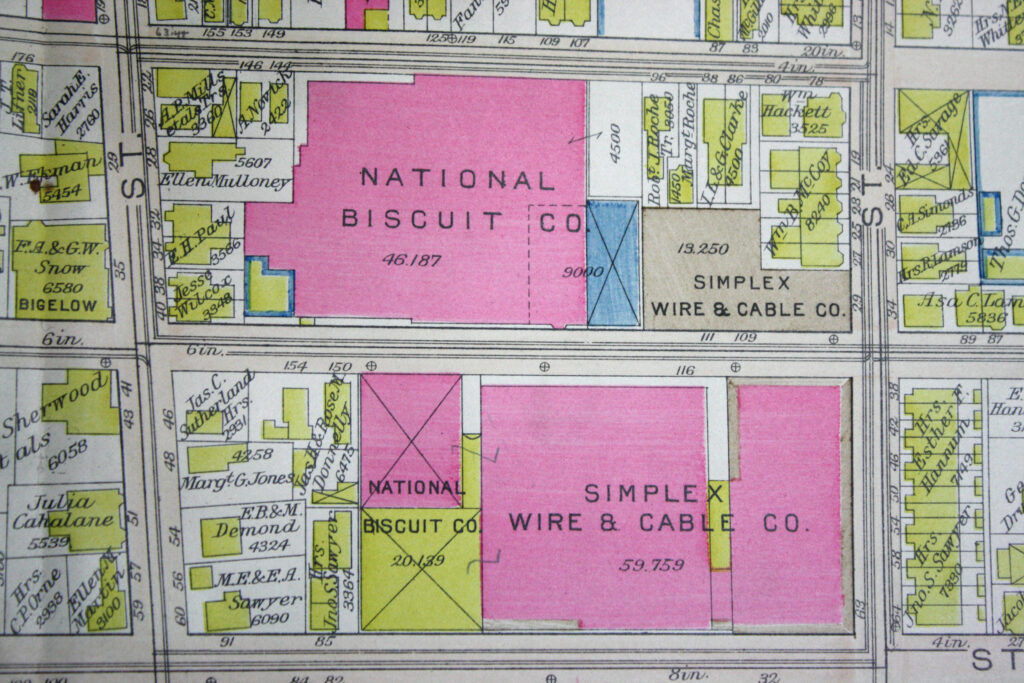

Nabisco

Kennedy Biscuit Factory, 129 Franklin Street (1869-present day as Nabisco)

The Kennedy Biscuit factory has stood here since 1869; it now stands as condominiums that bear the name Kennedy Biscuit Lofts.

Fig Newtons were first made here in 1891 and their shape, taste, and size have not changed since, even as Kennedy Biscuits merged with other bakeries in 1898 to form the National Biscuit Company, which we know as Nabisco, maker of Oreos and other cookies and crackers.

There is some speculation about the naming of the Fig Newton. One theory claims that the man who invented the machinery that makes Fig Newtons was so proud of his work that he named the cookie after Sir Isaac Newton. This is untrue, though. Fig Newtons were named after the nearby town of Newton, Massachusetts. The original Kennedy Biscuit Company named all of their products after surrounding communities, including cookies and crackers called Shrewsbusy, Harvard, and Beacon Hill. The company obviously had strong local ties: Frank A. Kennedy was the first to prepare Boston Baked Beans in hermetically sealed cans.

Though we’ve cleared up the misconception about the name Fig Newton, Nabisco has other brand names of unknown origin. For example, Lorna Doone cookies are only assumed to be named after the Scottish heroine Lorna Doone from R.D. Blackmore’s 1869 novel of the same name. No record exists as to the exact motivation behind the name, but in 1912 when the cookies were introduced, shortbread biscuits were considered a product of Scottish heritage.

Even Nabisco’s most popular cookie, the Oreo, has a little mystery. Oreos were introduced in 1912 and little was written about the naming because Nabisco did not have high hopes for the cookie. Theories for the name include 1) it was inspired by the French word for gold, or, a color used on early package designs 2) it comes from oreo, the greek word for mountain, because the first test cookies were hill shaped.

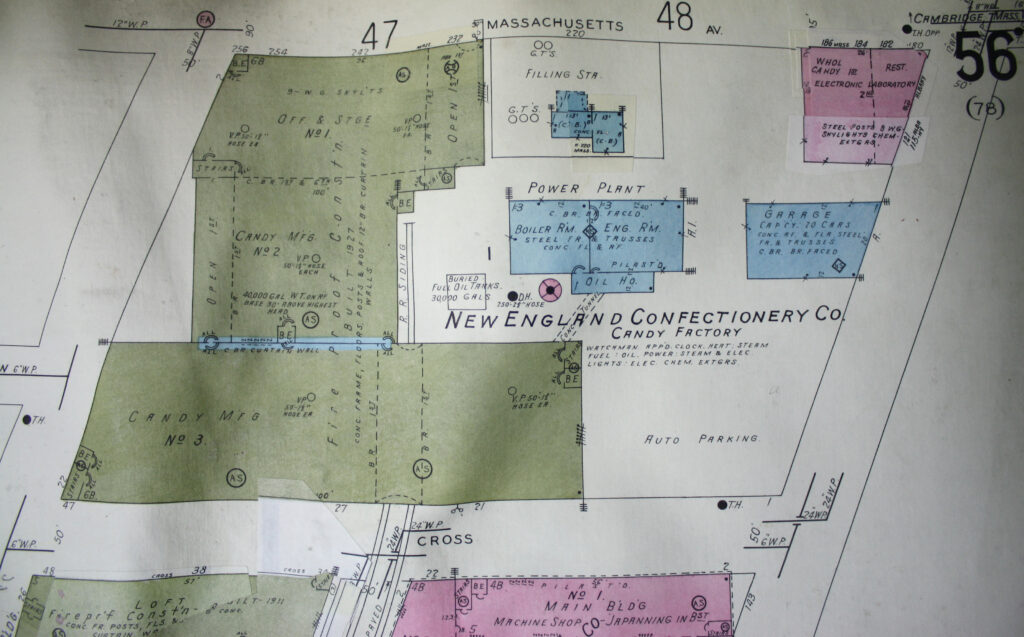

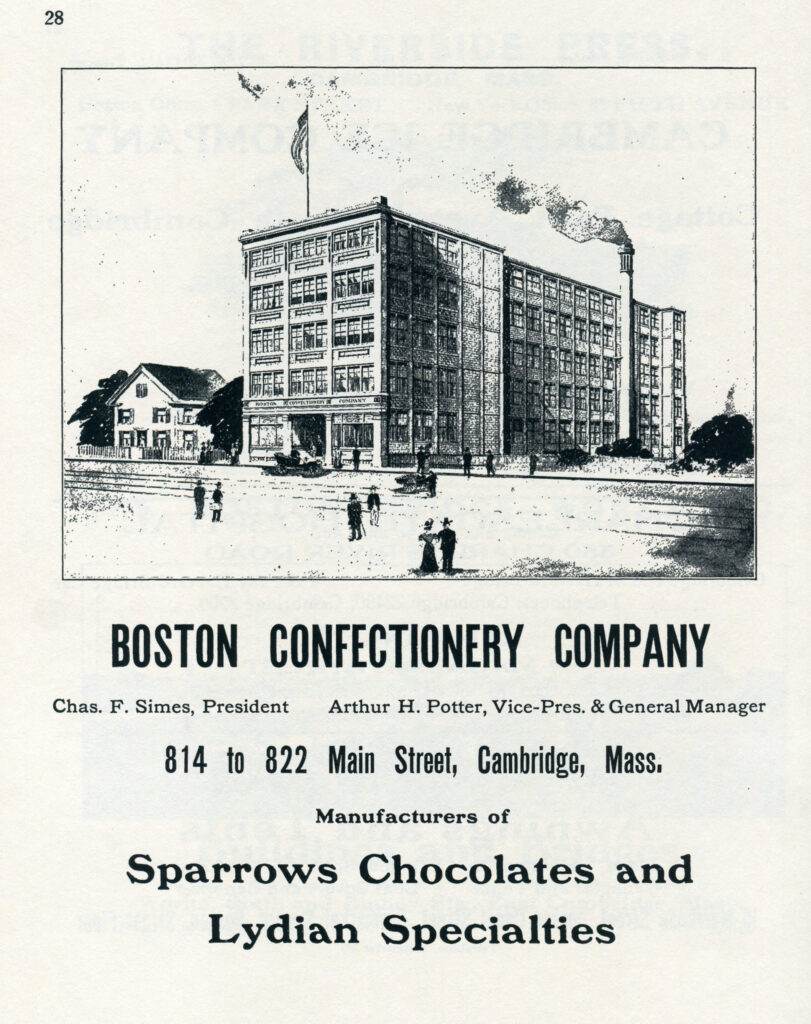

Necco (New England Confectionery Company)

254 Massachusetts Avenue (1847-present)

From 1927 until 2003, NECCO was headquartered in this building, and its water tower painted to replicate the familiar NECCO wafer roll was an iconic part of the Cambridge skyline. In 2004, NECCO moved production and headquarters to Revere and the building was occupied by Novartis Biomedical Research and the water tower was redesigned with a double helix.

When built in 1927, this factory was the largest in the world devoted to candy making. In fact, many of the features that made the NECCO building state of the art in 1927 also made it ideal for conversion to lab space. Made of concrete instead of steel frame, the building resists vibrations. Additionally, floors between 9-14 inches thick can hold as much as 250 pounds per square foot. When constructed, the floors were strong enough to support storage tanks, mixing vats, conveyer belts; now, they house robotics and screening machinery used in drug research.

The Novartis conversion of the factory was a $175 million project partly to remove sugar spores in the pores of the walls and sticky residue from the floors.

NECCO had one of the richest local histories in the industry. It dated back to 1847 when brothers Oliver and Silas Chase patented the first American candy machine and started producing sugar wafers. Early versions of the candy were distributed to Union soldiers during the Civil War.

In 1901, Chase and Company merged with Ball and Forbes and Bird, Wright and Company, two other Boston-based producers, to become the New England Confectionery Company. In the 1930s, Admiral Byrd, who brought Squirrel Nuts to the South Pole, also brought along NECCO wafers. In 1938, NECCO became the first candy manufacturer in the country to introduce a molded chocolate bar having four distinctly different centers encased in a chocolate covering. The Sky Bar was first announced to the public by means of a dramatic skywriting campaign. In the early 1940s, NECCO turned over a portion of this plant for manufacture of war materials and also used all of its candy facilities for providing rations to armed forces of WWII. NECCO wafers do not melt and are practically indestructible during transit, making them perfect to ship overseas to the troops. In 1945, the blackout and curfew in Times Square, New York was lifted on VE-Day after three years of darkness; NECCO’s Sky Bar advertisement was one of only six display signs that had their lighting equipment ready.

After the war and through the 1990s, NECCO acquired small candy companies throughout the U.S. and Europe, and the right to manufacture their trademarked candy bars. Thus, while still loved as a regional brand, NECCO transformed itself into a national conglomerate and avoided being devoured by larger companies.

By the early 60s, with candy giants gobbling up revenues, NECCO neared insolvency. The company was forced to sell out to BYS, a holding company, and in 2007 to American Capital Strategies. But NECCO managed to hang on, thanks mostly to its wafers and Valentine’s Day conversation hearts. In the 80s the company started buying out struggling competitors. There was no shortage: Some of its acquisitions include Candy House Buttons, Stark, maker of the Mary Jane, and the Clark Bar of Pittsburgh.

After leaving Cambridge in 2003, NECCO set up shop in nearby Revere, Massachusetts, where it was the city’s largest private employer. Unfortunately, NECCO’s story came to an end in 2018, when the factory was sold; it now houses an Amazon.com warehouse.

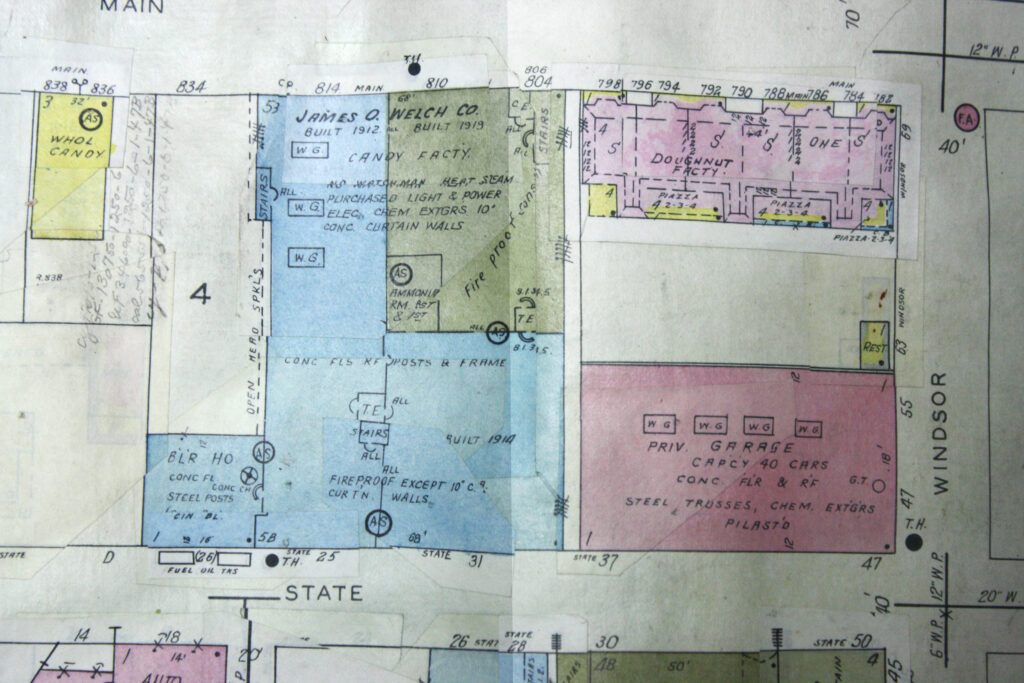

James O. Welch

810 Main Street (1927-1963)

This is the original factory of the James O. Welch Company, founded in 1927 and makers of Junior Mints, Sugar Daddies, Sugar Mamas, and Sugar Babies, among other candies. It is the last local factory still in operation, but it is no longer locally or independently owned. The company was bought by Nabisco in 1963, and James Welch acted as director for Nabisco until 1978 where later his son would act as president. The Welch brands were then sold to Warner Lambert in 1988 and finally to Tootsie Roll Industries in 1993. Tootsie Roll still produces more than 15 million Junior Mints a day, all from this location. Tootsie also bought out the Fox Cross company, the first stop on our tour, and continues to make Charleston Chews.

An interesting side note, James Welch’s brother Robert owned the Oxford Candy Company, a rival local confectionery that did not survive the depression. Robert moved to his brother’s business and stayed at the James O. Welch Company until 1956. When he left the candy business, Robert thought it natural to segue into radical politics. In 1958, he co-founded the John Birch Society, an advocacy group that supports anti-communism, limited government, a Constitutional Republic and personal freedom.

Although the public would love to glimpse inside these seemingly magical buildings, they are closed to the public. Major candy manufacturers, particularly the big three of Nestle, Hershey, and Mars, are notoriously secretive (not unlike what is depicted in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which Roald Dahl actually based on the exploits of the Cadburys and the Rowntrees, who routinely sent moles to spy on one another’s operations).

There are two reasons that espionage remains such a big anxiety in the candy industry:

- You cannot patent a chocolate bar or piece of candy. You can patent a name and a wrapper and logo, but the recipes and ingredients are fair game, making it possible for a competitor to sell a copycat of your product.

- The staple ingredients of most candies are quite similar, meaning the vital data resides in manufacturing processes.

It’s rumored that the major candy companies are so paranoid about spies that they even blindfold outside mechanics who come to work on machinery.

Toscanini’s

899 Main Street (1981-present)

In some ways, candy and ice cream are connected.

Ice cream actually has a deep local history. Boston’s Frederic Tudor, known as the Ice King, helped to make ice cream the international cultural staple that it is today. He revolutionized the way not only Americans, but people worldwide, eat and drink. From the 1830s to 1890s, the Tudor Ice Company harvested ice from Walden Pond, Fresh Pond in Cambridge, and other lakes in New England and shipped it to the American south and the Caribbean, Europe, and India. As an ice sales technique, Tudor demonstrated home-style ice cream making all over the world. Ice cream and chilled beverages became summertime staples. Additionally, a dependable ice supply made it possible to deliver fresh meat, seafood, and dairy products without them spoiling.

In Cambridge, ice cream was first served at high end restaurants and hotels. Once it became a commodity, ice cream was manufactured here by companies like White House Ice Cream and General Ice Cream Company. In Charlestown there was Hood Creamery. Cambridge even had ice cream cone manufacturers.

Once the mechanical ice cream maker and the soda fountain machine were invented, ice cream parlors like Boston’s Bailey’s which opened in 1876 became community meeting places. Ever since, the Boston area has been blessed with independent ice cream makers.

Steve Herrell in Somerville was the first person to make the wonderful pairing of ice cream and candy. In the late 1960s, Herrell was first introduced to the Heath Bar. He fell in love with the flavor and thought it would make an excellent addition to ice cream. When he opened his Steve’s Ice cream shop in 1973, instead of having premade flavors, Steve had his staff mix freshly made ice cream with candy or other confections based on customer requests. He called the toppings smoosh-ins and trademarked the name. Later chains took the smoosh-in concept and applied it to their own operations, creating a whole new industry around it. The popular Cold Stone Creamery now uses this model, as does Dairy Queen for its Blizzards and Wendy’s for its Twisted Frosty. Joe Crugnale, who bought the company in 1977 and would later found Bertucci’s, even claims that Ben and Jerry’s was a takeoff from the Steve’s model. Apparently Ben Cohen would come in all the time as a customer and take pictures of the ice cream and ask lots of questions.

Steve’s paved the way for the independent gourmet ice cream companies in Cambridge today, like JP Licks, Emack and Bolio’s and of course Toscanini’s, whose owner Gus Rancatore apprenticed with Steve Herrell years ago.

Explore Our Photo Gallery:

This tour was originally written in 2010, and updated in 2021. Know of any further updates? Email us at info@historycambridge.org