Watershed: An Excursion in Four Parts

by Emily Hiestand

First published by The Georgia Review and Beacon Press in 1998. Updated slightly in 2021 for publication in This Impermanent Earth, and in 2024 for History Cambridge.

Part One | Street

Like travelers who want to keep some favorite place from being overly discovered, the residents of our neighborhood sometimes confide to one another in a near-whisper, “There’s no other place like this in the city.”

It’s not a grand neighborhood, only a modest enclave on the fringe of the Boston metropolis, but visitors who chance upon our streets are routinely surprised. They remark on the quiet of the area, on the colonnade of maples whose canopies have grown together into a leafy arch over the street, on the many front porches (which older residents call their piazzas), and on the overall sense of being in a little village.

This small urban village is situated in the territory long represented by the late Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, who served in the U.S. Congress for thirty-four years, nine of them as Speaker of the House. Our streets are part of his “lunch-bucket liberal” district, a working-class neighborhood located on land that formerly held such things as the city’s poorhouse, blacksmith shops, and tanneries. The earliest inhabitants of our streets were predominantly French-Canadian, families and young men fleeing British persecution, streaming south from Nova Scotia, Quebec, and the Iles de la Madeleine. That early history explains why our inland houses and streets feel curiously like a small fishing village; the architecture of the small cottages, the exterior stairs and porches, even the way the houses are sited — close to the sidewalks with miniature front yards — are all transplants from the maritime villages of Acadia.

Immigrants from several other countries were also lightly represented in the early history of this neighborhood. The streets immediately surrounding the French-Canadian enclave were home to Irish, Italian, and West Indian immigrants, and to African-Americans migrated from the American South. From the beginning, our neighborhood has had a diverse population, and universally, the older residents who grew up here recall that these streets were not contested territory, which is something of a rarity, then and now.

Together, the varied people of this end of town created a way of life based on dogged work and devotion, donuts from Verna’s coffee shop, tolerance, fraternal clubs, church, and church bingo. The early neighborhood tone can be gleaned from one widely observed tradition, which was a principal entertainment on summer evenings. The activity consisted of residents sitting on their front porches after supper and talking to one another and to passersby. “Sitting out,” they called it. The close-set houses with facing porches, rows of shade trees, and the intimate scale of the streets all contributed to making this neighborly activity possible.

At the end of a road, on the edge of town, our neighborhood was long a modest backwater, sociologically and geographically remote from other parts of Cambridge. As our neighbor Alice, who has been living here for seventy-eight years, puts it: “No one came down this way unless they lived here.” But Speaker O’Neill, a pure product of these streets, took the local, big-hearted ethos national, where it made a difference across the length and breadth of the land.

“The early neighborhood tone can be gleaned from one widely observed tradition that was a principal entertainment on summer evenings: residents sitting on their front porches after supper and talking to one another and to passersby. ‘Sitting out,’ they called it.”

Photo credit: iStock

The bones of the early demographics of this street are still visible where the names on scattered mailboxes read Beauchemin, Arsenault, and Ouellette. In keeping with its original character as a portal into the city, our neighborhood has more recently become home to new citizens from India, Haiti, China, and Cape Verde, as well as to local writers and artists seeking affordable housing. It is also a peaceful place to work, the quiet engineered by a rabbit warren of one-way streets that deters incidental traffic from attempting the neighborhood, creating a precinct that is, by city standards, serene.

By day you can hear the tinkle of a small brass bell tied to the door of the mom & pop store across the street; by night, the lightly syncopated jazz of crickets and katydids rises from our small yards. Not too quiet, though. The bells of St. John the Evangelist peel on the quarter hour, and Notre Dame de Pitié rings its three great Belgian-made cloches — bells named Marie, Joseph and Jesus. At Christmastime Notre Dame plays the carols “Venez Divin Messie” and “Dans Cette Étable.” Several times a day, a train hurtles through a nearby crossing, blowing a classic lonesome whistle; in the late afternoons clusters of children come by our house after school, the girls singing, the boys bouncing basketballs en route to the corner park; and at night festive teenagers sometimes roil along our sidewalks, releasing what Walt Whitman proudly called barbaric yawps.1

Not far from our street is a lumberyard, a Big & Tall men’s shop, two grand churches, the best Greek restaurant in town, and two fortune-telling parlors. There is a genetics lab in our neighborhood, close to a Tex-Mex bar and grill where any escaping DNA on the lam could probably hide for days. There are fishmongers, lobster tanks, and think tanks here, and a storefront dental office with a neon molar in the window. There is a candy jobber and the Free Romania Foundation. There used to be a fast-food shack, named Babo’s, that had a sweeping modernist roof, designed by a local disciple of the architect Eero Saarinen. There are sushi bars with sandalwood counters, pizza parlors, and, recently, several nail salons. It is a dense, urban neighborhood, baroque with energies, more than anyone could ever say. Just last year we were all stunned to hear that a cigar-smuggling ring was operating in a house not too far from ours. According to the surprised neighbors, the people who ran it were “very polite.” Even more surprising, to me, was the discovery that most of our neighborhood exists on land that was — not so very long ago — a vast and ancient swamp.

Part Two | Swamp

The vast wetland began just north of the clam-flats along the Charles River and lay about nine miles inland from the coast. “The Great Swamp” it was called by the earliest English settlers who inked its features on their maps. Not an especially imaginative name, but a tremendously accurate one for the acres of glacially sculpted swampland, a place laced with meandering slow streams and ponds, humpbacked islands that rose from shallow pools fringed by reeds, and brackish marshes home to heron rookeries, wild rice, fish, and pied-billed grebes. For some ten thousand years, the great swamp had been evolving, preening, and humming.

The conditions for a swamp of such magnitude emerged as the last North American glacier melted and retreated, and the bowl-like shape of our region (the Boston Basin) became a shallow inland lake, an embayment contained by surrounding drumlin hills. Most locally, the waters were corralled by a recessional moraine — whose gentle bulk still slants across our city — and by beds of impervious blue clays under layers of gravel and a watery surface. The first human beings to arrive in this watershed would have found the vegetated marshes and swampland sprawling around two largish bodies of water, one of which is the amoebal-shaped pond known today as Fresh Pond.

I have lived close to Fresh Pond for most my adult life and had frequented its shores for years before I came to know about the former swamp. If pressed, I suppose I would have realized that something must have formerly existed in the place where there is now a megaplex cinema and an organic market where the cheese department carries small, ripe reblachons that delight my husband Peter. I don’t think that I would ever have guessed that the shopping plaza was formerly a red maple swamp, a distinctive area within the larger swamp, with smatterings of rum cherries and tupelo trees, with water lilies, pickerel weed, and high-bush blueberries “overrun,” said one habitué, in vines of flowering clematis.

I first learned about this former reality from the journals of William Brewster, a late 19th century Cambridge native and ornithologist, and curator of birds at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard. Not long after learning about the swamp, which Brewster explored throughout his life, I had occasion to drive to the Staples store in the Fresh Pond Shopping Mall. There, walking across the parking lot, I noticed my mind half trying to believe that if we could jackhammer up the acres of asphalt, underneath we would find — oh, not entire squashed red maples and blueberry bushes, but some incipient elements of a swamp, some slough or quagmire or marshy sponge — something of the liquid world lost to the single, dry word mall.

In truth, I like the mall. Its designers thought too little about the pleasures of shadow, light, and coincidence, and visually-speaking, this standard shopping center seems unworthy of replacing a notable red maple swamp. But the mall faithfully serves up shelves of many excellent goods: pens and paper, goat’s milk soap, native corn, good running shoes, French wine, and radio batteries. There are birds-of-paradise flowers at this mall, and a newspaper-vending box whose door opens on papers resting inside in a trusting stack. I also am glad for the adjacent utility station whose gray transformer towers carry the cables that step down voltage from the Northeast grid to a pulse our local wires can handle. There is a word to be said for the cement-block home of Inmetrix, and the eight gold ballroom-dancing trophies on the sill of one of the company’s windows, and another word for the restaurant that stands over a one-time rookery serving a dessert named Starstruck Sundae.

Certainly, by middle age one knows that ours is a paradoxical paradise, that all times, all lands, all selves are an alloy of scar and grace, that blight may turn to beauty and beauty to blight, like mischievous changelings teasing the stolid. Certainly, we all know that our lands, our countries, can be carnivals of misrule, as well as places of redemptive humanity. Still, this particular news, a whole gorgeous red maple swamp gone missing, hit me hard. I seem to have inherited the gene for liking to spend time in marshes and estuaries, floodplain forests, and cypress swamps. The Great Swamp of this region had the usual wetland virtues (functioning as a nursery for life, an aeration, and a sponge that prevented flooding), and it presents my mind with a nice conundrum to realize that the emergence of our dear neighborhood contributed to the demise of this wonder.

Perhaps I also brooded over the great lost swamp because I had attained an age when sympathy for vanished things comes easily, when we are aware of mortality as real and not some absurd concept that has, in any event, nothing to do with ourselves, our only parents, and our irreplaceable friend. Certainly, I was beginning to like the past more as people, places, and ambitions receded into it and became its populace. And perhaps that is why I began to go on long walks around the former contours of the swamp, seeking its traces and remnants.

“Certainly, by middle age we all know that our lands, our countries, can be carnivals of misrule, as well as places of redemptive humanity. Still, this particular news, a whole gorgeous red maple swamp gone missing, hit me hard.”

Fresh Pond; photo ©2005 Emily Hiestand

As it turns out, a glacial work is impossible to eradicate entirely. It is true that we are not going to find any quick phosphorescence of life under the asphalt that now covers so much of the former swampland. But vestiges of the swamp survive in a brook trickling through a maintenance yard, in a slippery gully of jewelweed, a patch of marsh, in the many wet basements of our neighborhood, and small stands of yellow-limbed White Willows (Salix alba). Great blue herons spend weeks on the river that runs alongside a local think tank, and there is still a lek ground where woodcocks perform their spiraling courtship flights.

Wild Saint-John’s-wort, healer of melancholy, grows here, also tansy and yarrow (Achillea millefolium), the spicy-smelling plant that sooths wounds — recently introduced species mingling with older ones. Killdeer, muskrat, and ring-necked pheasant (the last a twentieth-century arrival) have been seen in a small floodplain forest not far from the commuter trains, and against all odds, alewife fish run in the spring as they have for millennia, coming upriver from the ocean to spawn in the dwindling freshwater streams. Here and there, in a secluded patch of these old wilds, it is possible to get lost.

One afternoon as I was driving home along a road that passes a mucky pond behind the Pepperidge Farm outlet, something huge began to lumber across the road. I stopped my car and watched as a low, round, dark creature — it was a snapping turtle — walked slowly across the road, going directly toward a roadside barbershop. The turtle was so large, with a shell easily four feet around, that it seemed to belong in a more exotic habitat, in a place like the Galapagos. Concerned about what a highway and a trip to the barbershop could hold for an old turtle, I was even more astounded to discover that our present-day city contained such a being. It walked deliberately, unaware of the dangers on every side, huge and unassimilated, a tragic-comic amalgam: Mr. Magoo and Oedipus at Colonus. As one by one the cars on that road came to a halt, and all the drivers got out, we stared together as the creature crawled across the macadam, lumbering like memory out of an unseen quarter.

•

“We will never know,” says Professor Karl Teeter, a linguistic anthropologist who lives across the avenue and next door to our friend, the historian Judith Nies. It’s an early fall afternoon and I am talking with Professor Teeter about our pre-European predecessors on this watershed, the Pawtuckeog and Massachusett people. For many thousands of years, the Pawtuckeogs migrated annually between the inland forests and the coasts of an area they called Menotomet. Their sensible, appealing seasonal rhythm was to spend winters sheltered in the forest, then move to set up summer camps close to the clam-flats and the swamp that provided fish and fowl, waterways, and silt-rich land for corn and beans.

Karl Teeter has spent his adult life studying the Algonquian family of languages, to which the Pawtuckeog language, Massachusett, belongs. Sadly, no living speakers of Massachusett survive, but Karl explains that the language is similar to the one spoken by the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy of Nova Scotia. He shows me how close the Massachusett word for “my friend,” neetomp, is to the Maliseet word nitap. When I ask my learned neighbor if he knows any native Massachusett names for the Great Swamp or its features, he says, “Place-names are the hardest to recover, and the swamp landscape has changed so much now that I cannot even speculate.” We sit for a while turning the pages of a large green book that holds the Pawtuckeog vocabulary. Karl says some words, and I pronounce them after him: kushka (it is wide), (nu)keteahoum (we cured him), kohchukkoonnog (great snows).2

As the Native culture reeled and collapsed in response to European diseases and violence, the swampland lay shimmery and resistant to the colonizing touch for another century. European settlers were revolted by the miasmic terrain, and their disdain made the swamp a natural ally in the cause of American independence. It was on the swampy, lowland outskirts of the Newtowne settlement, safe from the Royalists who lived on higher ground, that the patriots could meet to plan their revolution. The gift of protection was not returned however; as soon as technology permitted, the victorious Americans began to eradicate the wetlands. Handsome orchards were the first incursions, then a single road built through the marshes — the “lonely road,” one writer called it, “with a double row of pollard willows causewayed above the bog.” Shortly before it began to disappear in earnest, the swamp found its poet in William Brewster, a shy boy who grew into one of America’s finest field ornithologists, and taught himself to write a liquid prose.

“When there was a moon, we often struck directly across the open fields, skirting the marshy spots … Invisible and for the most part nameless creatures, moving among the half-submerged reeds close by the boat, or in the grass or leaves on shore, were making all manner of mysterious and often uncanny rustling, whispering, murmuring, grating, gurgling and plashing sounds.”

In that passage, Brewster was remembering his boyhood days. Later, just after the turn of the century, when the wide river that had drained the swamp was narrowed and straightened, and began to receive the discharge of a city sewer, Brewster had to write:

“Thus has [the Menotomy] become changed from the broad, fair stream … to the insignificant and hideous ditch with nameless filth which now befouls the greater part of the swampy region through which it flows.”

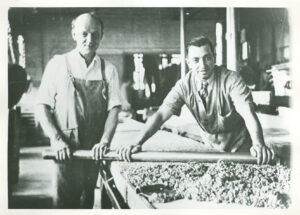

Only naturalists like Brewster and the rare person not enamored of the industrial adventure sorrowed when a stand of pines and beeches was cut to make way for an abattoir, or when Fresh Pond was surrounded by icehouses and machinery to cut ice in blocks to be sailed in sawdust to Calcutta, Martinique, and Southern plantations. Rail lines appeared just before mid-century, and the story then begins to go quickly: more swamp drained for cattle yards and carriage factories, and, after vast beds of clay were discovered, acres covered in the pugging-mills, chimneys, and kilns of a brickworks that turned out most of the bricks that built red-brick Boston.

Close by the brickyards, workers constructed modest wooden cottages on the edge of the dry, sandy plain adjacent to the swamp. The malarial epidemic of 1904, and its many small caskets, aroused the Commonwealth to civil engineering projects designed to eliminate what remained of a wetland then commonly referred to as “the menacing lowlands” and the area of “nakedness and desolation.” Streams were channeled and sunk into culverts; one large area was dredged and filled to make the site for a tuberculosis sanitarium. Over the next decades, the ever-dwindling wetlands were filled for pumping stations, suburban subdivisions and veteran’s housing, for chemical plants, office parks and playing fields, a golf course, a gas storage depot and a major subway terminal. In a nod to an earlier incarnation, the terminal is named “Alewife,” for the small, blear-eyed herring that was the fertilizer for the cornfields that sustained both Native and early European settlements.

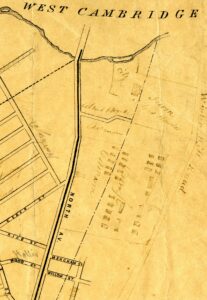

Laying a modern map of our part of the city on Brewster’s ink map, I can cobble together an overlay. The place on the old map marked as “large oaks & willows” is the site of Porter Chevrolet. The spot marked “muskrat pond” is the Fresh Pond Fish store. “Heronry of night herons” is now Bertucci’s Pizza parlor in the Alewife T-Station complex. “Pine swamp” has become a grid of two-family houses. Each change was welcomed, was cheered, by the bulk of the population in a country where land seemed unlimited, where swamps were vile and filling them an act of civic heroism.

“European settlers were revolted by the miasmic terrain, and their disdain made the swamp a natural ally in the cause of American independence. It was on the swampy, lowland outskirts of the Newtowne settlement, safe from the Royalists who lived on higher ground, that the patriots could meet to plan their revolution.”

Alewife silver maple floodplain forest, photo ©2005 Emily Hiestand

Once people hear that you are out walking around the neighborhood, nosing into the past, they send you pieces of folded, yellowed paper, copies of photographs and letters, and bits of stories. “I’m not a historian,” I had to say, “I’m not writing a proper history.” But people are generous; they want to help make your picture clearer, and they want a repository for memory. Along with paper and stories, I was also shown a horseshoe and a very old, red brick stamped with the letters NEBCO (which stands for New England Brick Company) that our neighbors Toni and John had found while digging in their garden.

As we stood in their backyard passing around the piece of rough iron, turning it over in our hands, Toni said they had learned that there was once a blacksmith shop on the site of their house. From another neighbor, I learned about a great-uncle from Barbados who had worked at the rubber factory. At the pizza parlor an elderly diner told me, “This was Lynch’s Drugstore. You could get a lime rickey.” At the electrician’s office, where a neon fist holds a bolt of blue lightning, the polite young electrician who is not one bit afraid of electricity but terrified of flying, says, “This was the Sunshine Movie Theatre.”

One day the mail brought a photocopy of a newspaper clipping from 1908. The headline read: “Famous Horses Raced Here.” And that is how I came to know the names Flora Temple, Black Hawk, and Trustee — some of the great trotting racehorses of their day — and the greatest of them, Lady Suffolk, a horse descended from the legendary Messenger. Trotting horses are the kind whose jockeys ride in the small, light vehicles called sulkies. Lady Suffolk was also apparently a saddle racer because the article mentions that her time for a mile “under the saddle” was 2:26, a time then considered so fast that the reporter gushed that it made her name “imperishable.” I mention her story to do my part to make that so.

My neighbor Joan, a woman who would be a leading member of the Society (if it existed) of Those Still Living in the House in Which They Were Born, remembers other now-vanished features of our landscape, including swimming ponds. “We used to swim in one of the clay pits after it flooded,” Joan tells me. “The one along Rindge Avenue, we called Jerry’s Pit. I remember my father sitting on the beach of Jerry’s Pit, bare-chested and showing off his tattoos. He had an Indian maiden on his shoulder, a goddess jumping rope on his arm, and a navigational star just above his thumb. By the time I was girl, all of the brickyards but one had closed, and there was trash and white powdery stuff lying around the yards. One summer, in the place where the apartment towers are now, the owners put up a sign that read ‘Clean Fill Wanted.’ Later that week, at night, someone dumped a dead horse in the pit. I can remember my mother and her friends laughing at that joke until they cried. There was not much sympathy for the owners of the pits because of the trash and the chemicals they had left on the place. Then there came the year the city closed our swimming pond because chemicals had leaked into it. The last clay pit closed in 1952, after it collapsed on a man. The collapse took the whole steam shovel that the man was operating, and the man himself. They could not rescue him. And that was the end of the clay pits. Later that pit became the town dump.”

By the 1970s, when I arrived in Cambridge, the dump had been operating for several decades, and had grown rolling foothills of unwanted material, dunes of newspapers and old appliances. Many of the trash hummocks smoldered with fires and all of them were circled by scavenging gulls. There were sometimes human gleaners at the dump, a man or woman salvaging a child’s highchair or a table.

In the 1980s, after years of behind-the-scenes planning, the landscape began to change again, this time into a city park with playing fields, hills covered in wildflowers, a restored wetland swale, and paths made of a sparkling, recycled material called glassphalt. On a recent Sunday, a croquet match was underway — older couples in traditional whites, younger players in flowered shorts and retro Hush Puppy shoes. Not far under the decorous new lawn and the wickets lies the refuse of four decades, capped and monitored, and threaded with pipes that allow gases to vent.

On contemporary planning documents the former great swamp is now called the “Alewife Area.” It is a place where a modern land-use opera continues to rage, a public policy drama complete with mercantile princes, dueling experts, public officials, citizens for whom the natural world is itself a form of wealth, and at least one man who sits with binoculars, at a high window of the apartment towers, scanning the landscape for barred owls.

The other day I went to the site of the former muskrat pond to rent a video of Bertrand Tavernier’s brooding 1986 film “Round Midnight,” in which jazz great Dexter Gordon plays the role of saxophonist Dale Turner, a fictional character based on Bud Powell and Lester Young, and their years at the Blue Note jazz club. The center of gravity may be the scene in which Gordon stands by his Paris hotel window talking to a young fan and aspiring musician. In a voice gravelly with age and hard living, Gordon tells the young man about the essence of creativity: “You don’t just go out and pick a style off a tree one day,” he says, “The tree is already inside you. It is growing, naturally, inside you.”

Isn’t that always the hope: that the things we make and build will be as right as rain, as a tree, or a glacier coming, gouging, then melting into something great.

Part Three | Alluvial Fan

By far the largest remaining feature of the Great Swamp is Fresh Pond itself, a 55-acre kettle hole lake surrounded by 160 acres of land. For more than twenty years I have circumnavigated Fresh Pond in all seasons, weathers, and moods, running or walking the serpentine path that winds around the water. I have run with various companions: an energetic Dalmatian named Gus; Anne, who was shedding weight and the wrong husband; and Jim, who joined me on night runs during which we admired how Porter Chevrolet’s sign laid streamers of color over the black sheen of the pond. Recently, I walked around the pond with my husband and smiled to hear him use the word “rip-rap,” a word that public works cognoscenti use to describe the rocks placed along a shore.

Hearing Peter use that word, casually, reminds me that he is still something of a public works hound, having started his career as a reporter covering a suburban public works department. During those years he often returned home from embattled, all-volunteer board meetings exhausted but enthralled by some exotica of the municipal infrastructure. The word also transports me again to the places Peter arranged to take me during our courtship: tours of water filter systems for the whey runoff from ice cream factories; state-of-the-art silicon chip factories; the power station at Niagara Falls. At the Niagara facility, we were given hardhats to wear, and were allowed to touch one of the three-story-high steel cylinder turbines that generate the power for the northeast corridor. (Talk about romance.)

Most often my companion on walks at Fresh Pond has been the surrounding land — filled with deciduous woodlands, a stand of white pines, and a small bog with weeping willows — and, of course, the pond itself, on which ice sheets rumble against the shore in winter and canvasbacks bob for their favorite food, wild celery, in fall. From time to time I exchange rambles at Fresh Pond for lap swimming, weight training, and a sauna. The health club in which these activities are accomplished has a skylight over the pool through which a backstroker can admire moons, clouds, pigeons, and falling snow. Handsome palms surround the aqua water. A nice person at the desk gives you a piece of fresh fruit. Driving away from these rituals, I have but a single thought (if you can call it a thought), namely, “Everything is fine.” The effect is testimony to the health club’s powers, and bringing any calm into this society is good, but the influence of Fresh Pond is even more salutary.

Circling Fresh Pond in all seasons has immersed me in a nuanced portrait of the year, and the pond’s fable of constant change within continuity has voided several slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. You can never predict what you will find: a sprawl of tree limbs after a storm; white cattail seeds streaming on a breeze; a sodden creature darting from the pond into the woods; crows cawing over glare ice. A place like Fresh Pond schools the eye, teaches one to expect surprise, and to rely on minute things — a dark red leaf encased in ice — to unlock meaning for the metaphor-loving mind. The patterns of light and shadow, thickets and tangles into which we can see but partially, the unspoken-for patches, the water surface that skates toward the horizon — all these are forms and shapes that offer possibilities for mind, for ways of being.

Technically however, Fresh Pond is a terminal reservoir and purification plant for the city water supply, and that is why it survives. A greensward at the entrance is named Kingsley Park for a famous Victorian president of the Cambridge Water Board. The Honorable Chester Ward Kingsley tells his story of the 19th century Fresh Pond water works pensively, as a man who loves his work and found few souls able to appreciate the grandeur of infrastructure: “I have never before had a chance to inform so many on this subject,” he writes, “and never expect another such opportunity.”

Kingsley was president of the Water Board for fourteen years; during his tenure, in 1888, Fresh Pond was ceded to Cambridge by the Commonwealth, the surrounding land included in order to preserve the purity of the water. “The City,” Kingsley writes, has taken about 170 acres, and removed all buildings therefrom. The pond contains 160 acres, and a fine driveway has been constructed all around its borders, nearly three miles long. With the water area and the land taken, this makes a fine water park of 330 acres. The surroundings of the park are being graded and laid out in an artistic way, beautifying the whole region and making it one of the most attractive places in the suburbs of Boston.” He continues, “It will thus be seen that in an abundant supply of excellent water…Cambridge presents one of the strongest inducements…for any who may be looking for a home where good water and good morals prevail.”

“A fine water park.” The phrase conveys the expansive spirit of a people for whom civic works embodied the democratic ideals: proper comportments of land and water would invite city dwellers into vital and uplifting pleasures, even moral life. It is not hard to imagine Chester Kingsley, bearded, appearing at civic parades in a handsome Water Board Officer’s jacket. Kingsley’s comrades in civic proclamations sound the same pleased, confident note: of one scheme for a riverside esplanade, the Cambridge park commissioner envisions that “launches may run from city to city” that “men [may benefit from] this little breathing-space…among beautiful surroundings.” It was not only a sweet boosterism that led to these claims. The Victorian planners, guided by Frederick Law Olmsted, had noticed the link between qualities of landscape and human well-being.

“A place like Fresh Pond schools the eye, teaches one to expect surprise, and to rely on minute things — a dark red leaf encased in ice — to unlock meaning for the metaphor-loving mind. The patterns of light and shadow, thickets and tangles into which we can see but partially, the unspoken-for patches, the water surface that skates toward the horizon — all these are forms and shapes that offer possibilities for mind, for ways of being.”

Fresh Pond, photo ©2004 Emily Hiestand

Reading the Victorian’s plans, their bursting pride and energetic efforts, one cannot but feel a tender spot for these city-builders who were helping to finish off the exquisite meadows and wetlands. It is hard to fault them when even today many seem not to have understood that only an astonishing one percent of the earth’s water is fresh. As the original wetland filtering system was destroyed, modern water planners turned to extraordinary engineering to deliver safe and plentiful water to the city.

One day in the winter of 1995, I visited Mr. Chip Norton, the Watershed Manager of Cambridge, in his offices in the City’s water works building. The building is a fine old thing with Palladian windows, a 1922 pump house, and a lobby that is a near-museum. The entrance area is empty save for a large yellow map of the reservoir mounted on the wall above a fading, dusty model of same, and a very dead rainforest plant near a peeling radiator. The floor is swaddled in brown linoleum, the walls painted pale pink with aqua trim, the effect is of age, time, and complete assurance that not one dime of tax money has been wasted here. And then, from the back of the lobby comes a luxurious sound — the rush of fast water spilling from three holding basins over aerating tiles. To be greeted by the roar and rush of water is surely the most brilliant possible entrance to a water department.

In the upstairs rooms of the building, city servants’ offices are outfitted with fresh carpets, recessed lighting, and the hum of sleek computers, which is well and good, but one prays that the City will have the sense to keep the aura of faded sanitarium that it has going downstairs in the lobby. (At least if this treasure has to yield to renovation3, move it to the Smithsonian as Calvin Trillin’s entire writing office was moved when The New Yorker moved from one side of 43rd Street to the other.)

As I pore over the dizzying engineering and planning reports that Mr. Norton has placed on a table in a small reading nook in the upstairs rooms, a woman behind the partition is talking on the telephone about where to get chicken salad sandwiches for lunch. She recommends Armando’s Pizza. Long silence. Next she offers to go to Sage’s Market, where, she says, they make a delicious chicken salad. Another long silence. Armando’s comes up again; the deliberations continue. From behind the other side of the nook a youngish woman playfully sasses a man who has apparently asked her to do some extra task. She replies that she has much more work to do than he does, and besides she has housework on top of that. “Peg always does your housework, I’m sure,” she says. The man agrees, takes the comments in stride, sighs, and then says that it’s time for a cigarette.

Along with such universal activities, the municipal water system seems to work by such devices as: having bought water rights a hundred years ago to sources in outlying suburbs; an eight-mile-long underground pipe; gravity; the chemicals alum and chlorine; testing; sedimentation beds and flocculation chambers; sand and charcoal filtration; monster pumps; holding tanks in Belmont; shut-off valves; and more gravity. Mr. Norton lucidly explained all the workings in front of an enormous, wall-size, hand painted map of the twenty-three-square-mile watershed for which he is responsible. Merely to gaze on the territory gives one a feeling of expansiveness and excitement — like that associated with mounting a campaign or planning an adventure meant to prove something.

The watershed is twice the size of the city it serves, and the wall map reaches well beyond the city, north to the Middlesex Fells, where Mr. Norton used to work and upon which he looks wistfully, perhaps recalling how peaceful life was in that rural outpost. In its scale and precision, the map gives the Water Department antechamber the air of a war room, the territories of conquest displayed in crystalline detail. But what makes this map wonderful is that its mission is the peaceful delivery of water for washing babies and boiling potatoes — well, for MIT’s little nuclear reactor, too, but mainly for aiding the daily lives of citizens.

Perhaps a woman who considers her bathtub the single most important device in the home, whose favorite work is watering plants, and whose day begins with cups of Assam tea can be forgiven for looking on Mr. Norton a bit dreamily as he pours forth the story of our city’s water. Like Mr. Kingsley before him, Mr. Norton’s chief responsibility is to protect the water quality within his watershed; at Fresh Pond, every use of the land must, he emphasized, be compatible with this goal.

Once, while explaining that Fresh Pond is the only place in the state (“maybe in the world,” his look implied) where dogs are allowed to range freely near a public water supply (thus, swim in and befoul it), the watershed manager let a wry look stroll across his face as he added, “But this is Cambridge.” He said this with a complex tone that bodes well for his tenure. As we spoke about the reservoir, I was also impressed by Mr. Norton’s crisp analysis of what we can and cannot control. “We cannot,” he said, “control the past, or birds, for instance. But we can control dogs.”4

This seemed as he said it like a gnomic reduction of wisdom, and I felt immediately relieved by the idea that the past can be let go of (as far as us controlling it), and also by the clear, calm way he said it. That’s right, I thought, admiringly, the past is over. What’s done is done. Later I recalled fiction, Proust and Nabokov, and the fact that modulating our idea of the past alters the present. But I know perfectly well what Mr. Norton means. He means, rightly, that he’s got a dealt hand. And he is especially not going to be able to control what happened to his watershed and Fresh Pond during the Pleistocene.

It was while sitting quietly at the metal table in the Water Department office, studying a heap of maps and surprisingly passionate master plans, with talk of chicken salad sandwiches in the air, that I suddenly, unexpectedly found myself descending again on the plumb line of time, plummeting far past the Great Swamp and its lost heronries to arrive in an entirely other incarnation of our neighborhood.

One Newton Chute provided the geology for the 1944 surficial geologic map of our area. Glancing back and forth between Chute’s map and his report, I slowly grasp that Fresh Pond exists, and that Peter and I make our home, on what was the eastern slope of a river valley. That is to say: where now exists the ground on which have variously stood drugstores, dray horses pulling blades, and apples in blossom was once merely a volume of air above an enormous river valley that ran southward from present-day Wilmington to the Charles River (which had not yet come into being). A rock terrace at about eighty feet below present sea level was the bottom of this deep, broad valley; the valley also held an inner gorge that cut down another ninety feet. The presence of the inner gorge indicates to Chute and his colleagues that “at least one important uplift of the land or lowering of sea level occurred during the formation of the valley.”

In part, it may be a recent appointment with my dentist, Dr. Guerrara, in which he filled a cavity — first boring it out, then filling it in discrete stages with various substances — that makes me riveted by the geological process by which glaciers filled the deep valley. As you may know, the modern human tooth cavity is filled first by a layer of calcium hydroxide, a liquidy paste like Elmer’s glue that hardens quickly on the floor of the prepared cavity; then with a thin, cool varnish, painted on to seal the tuvuals; finally, with the silver amalgam (copper, silver, tin, mercury) that is tamped in, carved, and burnished. The gorge in one’s mouth, as these minute temporary spaces feel to the tongue, is topped up. This is very like what happened all over New England about twenty thousand years ago, in the Pleistocene.

“’We cannot control the past, or birds, for instance,’ Mr. Norton said. ‘But we can control dogs.’ That’s right, I thought, admiringly, the past is over. Later I recalled fiction, Proust and Nabokov, and the fact that modulating our idea of the past alters the present. But I know what Mr. Norton means. He means, rightly, that he’s got a dealt hand. And he is especially not going to be able to control what happened on his watershed during the Pleistocene.”

A glacier covered New England during the Pleistocene; image via iStock

Chute identifies ten principal events in the centuries-long process by which an old valley was filled with successive layers of till, clay, peat, and gravel — materials pushed, trailed, and extruded by a glacier advancing and retreating over the land, moving south and east, a chthonic grading of the surface. Chute accompanies his glacial geology with a map that shows which of these glacial fill events figure on the current surface, and where. With mounting excitement, I locate the area of our street on the map: our home ground is Outwash 4, the eighth event, an outwash of sand and pebble-sized gravel that occurred as

a large alluvial fan spread southward over the “rock-flour” clays deposited in the exciting seventh event, the clays that would have such consequences for our neighborhood. A small ridge two blocks away, which we now know as Massachusetts Avenue, is thought to be “too high to be part of the fan” and probably was overlayered by its powerful flowing outwash.

I sit back in the Water Department’s chair, nearly faint from the morning’s events, and my idea of home rearranges itself once more, assimilating the knowledge that we live not only atop a lost swamp but also over a buried river valley and on an alluvial fan. It changes things, everything somehow, to know that during all the years I yearned to live (for a while) in a bucolic valley, my wish has, if prehistorically, been true. And what shall we make of the news that we dwell on an alluvial fan? While the fine sandy fan was spreading out, Fresh Pond must have still been entirely occupied by a stagnant ice block, for, as Chute reasons, “if the fan had been deposited after the ice block had melted, the depression occupied by the pond would have been filled.”

Even the alluvial fan does not prepare me, though, for the fact that our neighborhood, our city, indeed the Eastern Seaboard from Virginia to Nova Scotia, takes place on a crust of earth that was once the west coast of Africa. The crust is named Avalon, and it arrived when a piece of Gondwana, ancient continent, broke away, swept across the ocean (not yet the Atlantic, but Iapetus), and collided with the old North American continent. Our most local crust came from the part of the earth that is today Morocco — and the only country that shares with the Boston Basin the lumpy-looking rock we call puddingstone. It has been quite a long while since these mighty things took place, and it is hard to say what, if anything, they have to do with the realpolitik taking place on the underlying Avalon. But, as always, the familiar when closely observed reveals itself as an exotic.

Beyond its transforming information, a U.S. Geological Survey report enthralls because of the language scientists use to convey glacial events: here there are “geophysical traverses,” “faults in overridden sand,” “uplift of the land,” and “marine embayments.” The souls who spin off these phrases in longish sentences that describe — calmly — seismic events that rumbled over millennia, sound as if they know what they are talking about, as if they know what is going on down deep, at the level of accurate subsurface information where knowledge is grounded.

Although I was born decades after early twentieth-century physicists had their near-nervous breakdowns at the implications of relativity, the fluid epistemology implied has come only slowly and imperfectly into my psyche, which seems to cling to a pre-modern, limbic hope for solidity. As my life’s education has proceeded, each new knowledge gradually reveals that it too rests on gossamer metaphor. Reading the geologists, I feel the tantalizing hope that with this vocabulary I might grasp the real nature of things. Perhaps here are the minds and ways of talking that take one through loose gravel, till and sand, through bands of clay, to bedrock. And if it all be gossamer, what better gossamer than bedrock?

Part Four | Navigable

One afternoon, circumnavigating Fresh Pond with a photocopy of an 18th century map in hand, I see that our local pond was once linked by a series of rivers to the Atlantic Ocean, that for all but the last hundred years of its existence our inland region had a direct channel to the sea. On the old map, the river Menotomy rises out of Fresh Pond, winds through the Swamp, joins the Little River and flows into the Mystic, which empties into the Atlantic. I also see that some vestige of that former water route would still be navigable by canoe. The Little River is extant, and flows into a stream called Alewife Brook, formerly the last stretch of the Menotomy. A present-day river guidebook tersely describes Alewife Brook as “not recommended,” but Peter and I cannot resist taking our canoe down the olive-green stream. As we float past lilies and half-submerged shopping carts, we will be moving along the oldest artery of our watershed.

The route will eventually take us through a lock at the Amelia Earhart Dam on the Mystic River, which prompts Peter to say, “We should get an air horn to signal the lock keeper.” I say, “Great,” because I have learned that Peter is always right about gear, and when it is needed: there was the time with a Maglite in the Everglades; the spare bike tire on a remote country road; and a sparkplug socket wrench on hand to fix a smoking car. Many times I have owed my happiness, and once my life, probably, to Peter’s skill with gear. He selected an air horn at the sporting goods store and together we read the instructions, which were very explicit, saying in essence: Do Not Use Your New Air Horn. It Will Destroy Your Ear Drums, So Just Never Use It. “Oh, they have to say that,” Peter said, hefting the little horn. “Some rude people take them to sporting events.”

The only other special thing we will need for this journey is an idea about where to land a canoe in a big-city working harbor. Our canoe is seventeen feet of a dull green material called Royalex, a stable boat with a low-slung profile, named in honor of the Victorian traveler Mary Kingsley, who liked to paddle in African swamps. We want to land the Mary Kingsley somewhere along the banks of the inner harbor, near the Tobin Bridge. On the early summer evening that Peter and I scout the harbor, we discover not a single take-out site for a canoe, but many other interesting things, including a marine shipping terminal, the titanic legs of the Tobin Bridge, a burned-out pier, the U.S. Gypsum Company, and a mountain of road salt recently offloaded from an Asian freighter. Near sundown, an oblique red light slants over pools of steamy gypsum tailings. This extravagant light and the sheer muscle of the place make for a romantic landscape. As is often the case, Mr. Emerson has been this way before, admiring the potentially fine face of industry. He writes:

It is vain that we look for genius to reiterate its miracles in the old arts; it is its instinct to find beauty and holiness in new and necessary facts, in the field and road-side, in the shop and mill. Proceeding from a religious heart it will raise to a divine use the railroad, the insurance office, the joint-stock company; our law, our primary assemblies, our commerce, the galvanic battery, the electric jar, the prism, and the chemist’s retort …. The boat at St. Petersburg, which plies along the Lena by magnetism, needs little to make it sublime.

On the other side of the river lies the city of Chelsea, nearly all galvanic battery — a welter of scrap metal yards, weigh stations, warehouses, sugar refineries, and gas yards, the last a sinuous complex of pastel pipes. As night comes, and a hazy fog begins to materialize, we happen on the Evergood Meat Packing Company, where beams of light from mercury vapor arc lamps rain down on a parking lot, carving the lot out of the night and lighting up this scene: three meat packers in long white butchers’ coats, the men running through the lot passing a soccer ball back and forth expertly. The ball bounces from a corrugated wall, skims under the axles of a fleet of trucks. The long white coats are brilliant in the vapor arc light, the fabric flowing, flapping like wings. It is the quickest glimpse, as now the road climbs a dark hill. From the summit, the city’s financial district is visible across the river, its lights flickering, cleaning crews at work. Down the hill, on the river itself, and moored to the bank, we see the object of our search: a small pavilion and public dock.

“The most succinct account of our river journey is that we launched a canoe amongst somnolent lily pads and took it out near a Brazilian cargo tanker.”

Lilies in the Alewife Reservation; photo ©2008 Emily Hiestand

•

The most succinct account of our river journey is that we launched a canoe amongst somnolent lily pads and took it out near a Brazilian cargo tanker. Our paddle begins on the Little River, where, passing the mouth of a narrow ditch full of appliances, engine parts, and a sodden teddy bear, we are passing the paltry remains of the wide Menotomy. Along one stretch, the Little River is so shallow that it is more a skim-coat of water than a channel; the dorsal spines of carp crest the waterline, giving the river the eerie appearance of being alive with silver grey eels.

As it deepens again, the Little River becomes Alewife Brook, and when we pass the gas station near Meineke Muffler, we are at the old site of a basketry weir, a spot that both Native Americans and settlers used for harvesting shad and alewives — the latter still plentiful enough in the nineteenth century to move one observer to write, “I have seen two or three hundred taken at a single cast of a small seine.” Up to the present day, new citizens come to this watershed in spring to catch alewives. On another day at the Mystic Dam, we meet three slender Cambodian men whose fishing gear consists of a box of large pink garbage bags. The men are barefoot, wearing dated bell-bottoms and white dress shirts and they fish from slippery rocks, dipping the pink plastic bags into the causeway spill. Although the numbers of the fish are greatly diminished, at this dam in spring they look abundant, flowing over the spill into the thin plastic bags like grains of rice from a bulk bin.

An alewife is an anadromous fish (“running upward”), and its presence in our watershed is known as ephemeral. The fishes are seasonal transients, coming from the ocean to freshwater to spawn. Continuing south now on the Mystic River, we are following the young alewives’ fall route back to sea. They would pass, as we do now, backyard barbeques and hammocks, and then the backside of a downtown, where retaining walls read “Dragons Rule,” and iron infrastructure swirls with organic patterns of rust and rain.

Here and there, trees overhang the river, dappling its surface of lily pads. As the river widens the tree break disappears. We pass by an Edison power plant, and under a bridge that bears eight lanes of interstate traffic. The Amelia Earhart Dam comes into view. Peter readies the air horn, and when the dam is close, he presses the small button. It delivers one of the loudest bursts of sound I have ever heard — next to the time a lightning bolt hit the house. The lock keeper likes the air horn, likes being hailed in the proper nautical way, and gives Peter a crisp salute. As our canoe glides into the narrow chamber, two powerboats hurry in behind us. The doors of the lock slide closed, the water rises, and when the lock opens again, the still, olive river water has vanished and we are in an ocean-blue chop with whitecaps.

The powerboats take off like rodeo cowboys on broncos, and I am wishing that we had something with a throttle too. As we move more slowly into the harbor and the wind picks up first tugboats, then small freighters appear. Conveyor belts, rigs, and tall booms are cantilevered over the water; an inverted silver dome built to cover twenty tons of unrefined sugar glints on the bank. By the time the big bridge looms into view, our canoe has shrunk to a bobbin — a bit of flotsam below the gantry cranes. We are gawking at the cranes when a rogue ocean swell rises out of nowhere, tosses the canoe several feet into the air, spins us a little, breaks across the side, slaps us full-face with salty water. The pavilion and dock are just visible now on the other side of the river, and as we struggle toward the landing in the chop, we marvel at the first people of this territory who took their thinner, lighter canoes out much farther, into open ocean, and up and down much of the Atlantic coast.

At the dock we are met by two small boys, brothers, who shyly stare and smile at the canoe, and within seconds of our invitation are in it, are touching its sides, gripping the paddles, putting on lifejackets, and not sitting too still but gently rocking the boat to get a feel for it. Their names, the boys tell us, are Ulysses and Erik.

I wouldn’t dream of making that up, and where else but a big-city waterfront would you expect, these days, to be met by the two chief heroes of epic seafaring? True to their names, the boys cannot take their eyes off our boat. They are intrigued by paddles. Fascinated by the weight and color of life jackets. Overjoyed by ropes, by tying knots. Eager to know what the canoe is made of. Running their hands over the cane seats and wooden thwarts. In love with all things nautical. Beside themselves with happiness when their father says, yes, they can take a short ride with us, just around the perimeter of the pier, not far. And when at last we must head home, the legends (as bold, as clever as ever) cajole us, insist on hauling some of the gear up the slight incline to our waiting car, where they are further enthralled by the every detail of mounting a canoe on a Subaru: how the canoe is lifted up by two people, how it is strapped onto the roof of the car, how foam clips are slipped over the gunnels, how ropes are laced and tightened.

Ulysses and Erik tell us that, yes, they were born here, in this city, but home is an island far from here, somewhere over the water. They each point out to sea, not exactly in the same direction. When the canoe has been secured in place, and all the gear stowed, the hero-boys shimmer away, and are last seen lying flat on their stomachs, their arms submerged in water up to the shoulder blades — as close to being in the ocean as boys on dry land can be.

Endnotes

- See Song of Myself, Verse 52, by Walt Whitman ↩︎

- In the years since I spoke with Professor Teeter, Jesse Little Doe Baird (SM, MIT Linguistics ‘00) launched the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, and has led a successful effort to revive the Wampanoag language, a dialect of Massachusett. The once extinct dialect is now spoken in the Wampanoag communities of southeastern Massachusetts on Cape Cod and the islands. Linguistic scholars think this is the first-ever revival of a lost language. ↩︎

- The Water Department buildings described in this essay were replaced in 2001, about four years after I first wrote this story. The new facility has state-of-the art-features and capacities, and a handsome Romanesque Revival exterior with large, arched windows that, as the Society of Architectural Historians writes, display “the awesome water process systems” inside. ↩︎

- Chip Norton served as the Watershed Manager of Cambridge for 23 years, from 1991 until his death in 2014. I am one of many people grateful for his vast knowledge and generous spirit. For his expertise, mentorship, friendship, and dedicated work, Chip earned the deep admiration, affection, and respect of his many colleagues and the Cambridge community. A Cambridge Day article about Chip Norton’s life and a posthumous stewardship award honor his enduring contributions to many “reservation projects, including Little Fresh Pond, the Northeast Sector, the Neville Community Garden, Maher Park, Butterfly Meadow, Black’s Nook, Glacken Slope, and Kingsley Park.” ↩︎

Copyright info

©1998, 2021, and 2024, Emily Hiestand. First published by The Georgia Review and Beacon Press in 1998. Updated slightly in 2021 for publication in This Impermanent Earth, and in 2024 for History Cambridge.

About the Author

Hiestand and her husband lived in the North Cambridge neighborhood described in this essay for 20 years. Her writing appears in magazines (including The Atlantic, Salon, and The New Yorker); anthologies (including Best American Poetry, The Norton Book of Nature Writing, and This Impermanent Earth); and many literary journals. She developed the communications program for MIT’s School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences and served as its director for 15 years. Earlier, Emily was the Literary Editor for Orion Magazine, working with America’s leading nature writers and introducing new themes (including environmental justice) into the magazine’s pages. She has served on the boards of PEN New England and the Associates of the Boston Public Library.