Self-Guided Tour: Women Activists of Riverside 50 Years After Suffrage

Stop 1: Begin the tour in Central Square

With the passage of the 19th Amendment one hundred years ago this past August (2020), American women won the right to vote. Rather than a culmination, this event marked the beginning of a long fight for equal treatment and equity that is still far from over. Fifty years after suffrage, classified ads for employment were still segregated by gender; battered women’s shelters did not exist, and abortion was illegal. The second wave of feminism emerged in the 1960s and 1970s amid movements for civil rights for Black, indigenous, and gay Americans, as well as the anti-war movement. With groups like Bread and Roses and the Boston Women’s Collective, Boston and Cambridge became a center of feminist activism.

Local feminist groups led marches, held consciousness-raising groups and conferences, and published books and magazines. In Riverside, women activists took over and occupied a building at 888 Memorial Drive demanding access to childcare, equal pay, and a space for women—a women’s center. Activists at the Cambridge Women’s Center would lead a movement to end “battering” (as domestic abuse was termed) and advocate for equal pay for all women’s work. Feminism was not the only issue that animated women in the Riverside community. Spurred on by issues of race, class and institutional power, women of Riverside demanded affordable housing, fought urban renewal policies and even challenged powerful corporate interests. The power structures at the time were dominated by men but women played a major role in the fight for social and economic justice, and to save homes and livelihoods.

Stop 2: Stroll down “The Ave”: Walk down Western Avenue toward the Charles River

The Riverside neighborhood, also known as “the Coast,” is a wedge-shaped slice of the city bounded by Massachusetts Avenue and River Street. Western Avenue—”The Ave”—runs down the center of the community. In the early 1800s, horse-drawn streetcars rattled down The Ave toward bridges over the Charles River to Watertown. The waterfront bustled with industry including the Riverside Press and the Arrow Shirtcollar Company. Salt marshes dominated much of the area near the river until the Charles River Dam was built in the early 20th century, preventing the natural ebb and flow with the tides. Many of the homes along Western Avenue date from the mid-1800s, with homes closer to the river built in the early 20th century as the riverfront marshland was developed.

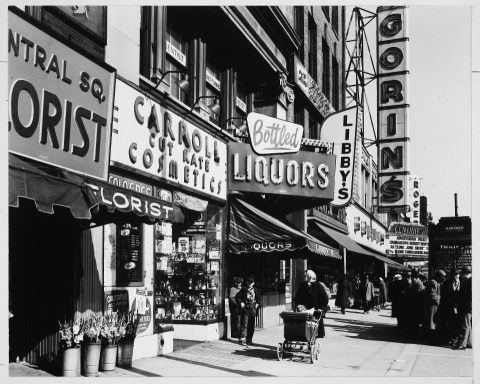

As you walk down Western Avenue, look for unusual box-shaped structures jutting out from some of the houses. These were small shops where the homeowners sold vegetables or meat. Most of them were added to houses in the early 1900s; they played the same role as corner stores do today. Stop at the intersection of Howard Street and Western Avenue where, until recently, there was a cluster of stores and businesses. Neighborhood residents did most of their shopping in Central Square where there were restaurants, two movie theaters, and many shops. Department stores like Gorin’s had furniture and housewares downstairs and clothing upstairs. At Carl’s Market, you could put fresh meat on your tab and, at Roger’s Jewelry, you could buy an engagement ring and pay over time. Residents never needed to go to downtown Boston; Central Square had everything.

Stop 3: Stop at the intersection of Howard Street, the center of the Coast’s Black community

The Riverside community was diverse but largely working class. By 1970, the population was just under 10,000 people. White residents included Irish and Greek immigrants who settled in the early twentieth century. As early as the 1890s, a sizable Black community was centered at Western Avenue and Howard Street. The community grew dramatically in the 1920s as more Black people migrated from the American South, particularly Georgia and Virginia, part of a national trend called the Great Migration. At the same time, immigration from the West Indies, specifically Barbados and Trinidad, accelerated. As mentioned at Stop 2, this part of Riverside is called The Coast by locals.

With factory jobs not available due to discrimination or lack of connections, many Black residents took jobs in skilled trades like carpentry and cabinetmaking. Though access to credit became challenging for everyone in the 1930s–and continued to be challenging for Black families–many were eventually able to purchase homes. By the mid-twentieth century, the community was thriving and had a commercial district with stores, offices, and an auto repair shop at this intersection. The Cambridge branch of the N.A.A.C.P.–a national civil rights organization–had an office at 205 Western Avenue and a mailing list of over 500 people in the late 1960s.

The Christian faith was important to the community, and churches played both a social and spiritual role. Neighborhood residents attended the two nearby churches: Western Avenue Baptist Church (1916) and Abundant Life (1917) at the corner of Howard and Callendar Streets. Other residents of different denominations attended St. Augustine’s African Orthodox (1886) on Allston Street in Cambridgeport and St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal (1908) and St. Paul’s AME, both on the other side of Central Square. You can walk this block and turn right on Dodge Street to get to the next two stops.

Stop 4: Turn right on Howard Street and walk to the Cambridge Community Center at 5 Callender Street

Segregation was not legal in Cambridge, but we know from oral histories that members of the Black community did not feel welcome at the local YMCA. In 1928, ministers from the four main black churches came together to found the Cambridge Community Center with the stated purpose of providing “…a center for the recreational, educational, and social activity of the people of the community who desire to make wholesome use of their leisure time.” Over the past 90 years, the Center has served as the heart of the Coast community, providing social, educational, and recreational programming. They offered sewing, carpentry, and ceramics classes for adults. For youth, they provided daycare, after-school care and Camp Cowemoki in the summer. Over the years, the Center’s Common Room has served as a meeting space for community organizations. In the late 1960s and early 70s, some of these were activist groups; the Center, however, remained non-political. Many of these groups were composed of and led by Black women.

The Riverside Neighborhood Association originated at the Center in 1956. At first, it was a social gathering among women of the neighborhood to discuss small problems. By the early 1960s, the association grew as discussions focused on issues of housing and fighting urban renewal plans. Another women-led group was the Committee of Concerned Black Parents that formed in 1970 in response to racial tension at the high school. Led by president Gertrude Block, the Center hosted their meetings and a series of workshops. Block and the committee demanded the immediate appointment of a Black deputy superintendent to handle Black student concerns. They also demanded Black studies curricula, a screening panel of Black community members in the hiring process of school employees, and the renaming of the Houghton School—an elementary school located on Putnam Avenue—to the Martin Luther King School, which was further transformed into the first experimental community school. The School Committee had unanimously agreed to rename the school in the wake of Dr. King’s assassination, however construction of the school had been delayed. The new King School finally opened in 1972.

Stop 5: Walk down Callender street toward Putnam Gardens and stop at Magee Street

Access to affordable housing has long been an issue in Cambridge and Riverside. During the Great Depression, the first federal housing projects such as Newtowne Court (between Maine and Washington Streets) opened in 1935 to white families and served a dual purpose: modernizing housing stock while clearing the “slums.” In front of you is Putnam Gardens which opened in 1953, as part of a second wave of state-funded public housing projects to address post-World War II housing shortages.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation deemed Riverside “hazardous” (redlined) for lending due to “infiltration of negro” and “low class occupants.” Residents had difficulty securing mortgages. At the same time, outsiders had their eyes on Riverside. In 1940, an MIT professor sent out a team of women to survey the Western Avenue “slum” area for redevelopment into low-cost private housing. In 1946, John Hancock Co. proposed a housing project called “John Harvard Town” under the state’s new urban redevelopment laws. It was never built, but in 1957, this same area (bounded by Western Avenue, Massachusetts Avenue, and Memorial Drive) was designated as the “Houghton Urban Renewal” under a new federal program.

At first, residents welcomed the Houghton Urban Renewal project, eager for federal funding to build much-needed playgrounds. By 1960, residents were concerned about the loss of housing and authorities sought to persuade them that “renewal” would not be as destructive as the “redevelopment” projects that demolished The Rogers Block (near MIT) and the West End in Boston. In 1960, all renewal plans were put on hold pending clarification of the route for the proposed inner belt highway plan. (See Stop 10.) Renewal was again greenlit in the summer 1961 and 500 people showed up at a meeting at the Community Center to voice opposition, charging that too many families would be displaced and unable to find adequate housing. The Riverside Neighborhood Association led the fight, asking: “What about the residents of color in the area, who will be hit the hardest?”

Stop 6: Walk along Magee Street to Putnam Avenue. You can see Peabody Terrace and the new King School.

In addition to the threats of demolition and displacement coming from the city, Riverside residents viewed Harvard as a looming behemoth–encroaching into the neighborhood, snatching up land, forcing evictions, and raising rent prices. Between the 1930s and the 1950s, Harvard expanded south from Harvard Yard developing housing for students along the Charles River. Built in the Georgian-revival style, the elegant brick “river houses” replaced coal and lumber yards on the riverfront without much resistance from the neighborhood. In the mid 1960s, Harvard pushed deeper into Riverside, erecting concrete towers which were in sharp architectural contrast to previous development, as well as to surrounding three-decker homes. In 1965, Peabody Terrace (22 floors) was completed on the former site of the Arrow Reverse Collar Factory. Mather House (19 floors in the Brutalist-style) replaced Kerry’s Corner, an Irish enclave, in 1970.

The growing resentment of neighborhood activists reached a boiling point in 1970. Their entreaties for a meeting with the Harvard Corporation had gone unanswered. Refusing to be ignored, they devised a plan to bring attention to their cause. On the evening of June 10th, 1970, Riverside native Saundra Graham and a group of resident-activists camped out overnight in tents in Harvard Yard. They planned to disrupt Harvard’s 319th Commencement ceremony the following day.

As Law School graduate William Weld spoke, a diverse group of 30-40 protestors including children mounted the stage at Memorial Hall carrying picket signs: “Get out of Riverside” and “Power To The People.” Saundra Graham shouted into a megaphone, “We are the oppressed . . . give us land and we will build housing on it. We are going to get some kind of commitment today or we are not leaving.” The commencement came to a standstill with the protestors refusing to budge. It only took about ten minutes for Harvard President Nathan Pusey to acquiesce to talks. Saundra Graham and the Riverside activists prevailed. The commencement would continue, but the Harvard Corporation was forced to face the community. (We will return to Saundra Graham and the story of housing at a later stop.)

Stop 7: Cross Putnam Avenue. Go down the small street along the Peabody Terrace garage. Turn left on Banks Street and walk to Hingham Street. Along the river, there is a historical marker for 888 Memorial Drive.

On this site in 1971, a group of women took over a building owned by Harvard University. Formerly the site of the Hingham Knitting Company (1914-1929), in 1971 it was used as a bookbindery by the Harvard School of Design. The large building was mostly unoccupied and slated for demolition. At the time, Saundra Graham was calling on Harvard to build affordable housing here and the occupiers wanted to act in solidarity.

At noon on March 6, 1971, in honor of International Women’s Day, thousands of women marched from Boston Common carrying signs and banners demanding women’s liberation and singing anthems like “Move on over, or we’ll move on over you.” In Central Square, Bread and Roses, a feminist socialist collective led a contingent of marchers away from the main route. They turned left on Pearl Street and right on Putnam Avenue to 888 Memorial Drive. More than 100 marchers swarmed the building. They demanded the creation of a “women’s space” as well as affordable childcare and reproductive rights.

Inspired by Saundra Graham, the women proclaimed solidarity with the Riverside community in their demands for affordable housing. The women draped a giant banner proclaiming “Sisterhood is Powerful” out the second floor window and painted “The Women’s Center” in bold block letters on the side of the building.

The occupation lasted ten days, from March 6th to March 15th, 1971. The occupiers were a diverse group of feminists—socialists, housewives, lesbians, and students. The atmosphere was celebratory, with dancing, hair cuts, and self-defense classes. Women took shifts and brought sleeping bags to camp overnight. Some women came out during the occupation. For most of the first week, the temperatures hovered around freezing and dropped into the 20s at night. By Thursday, it even snowed and women engaged in joyful snowball fights. Harvard wanted the women out but was concerned about the optics of a powerful university bullying a group of women. At one point, Harvard turned off the heat and electricity. The women were able to turn the electricity back on but not the heat.

A judge issued a court-order for the women to leave. With news that a police “bust” was imminent, there was disagreement among the occupiers about how to respond to a potentially violent confrontation. Ultimately, a group of supporters offered $5,000 to support the creation of a women’s center in another location. The occupation came to a peaceful end and the Cambridge Women’s Center came into being. (We will learn more about the Women’s Center at a later stop.)

Stop 8: Walk across Hingham Street to the park bounded by Memorial Drive and Western Avenue

Saundra Graham, a lifelong Riverside resident, was a single mother of five when she became a member of the Cambridge Community Center’s Board of Directors in 1968. In 1970, she was chosen as president of the Riverside Planning Team. Her takeover of Harvard’s graduation in June of that year earned her a reputation as a “fireball” and a “fearless fighter.” The women who took over 888 Memorial Drive were inspired by Graham and picked the site to bring attention to her call for affordable housing at this location, known as Treelands. When talk turned to putting a women’s center at Treelands, Saundra Graham went in to meet with them, concerned that their demands would cloud the on-going negotiations between the community and Harvard. The women responded; not wanting to speak over or for the people of Riverside, they called for direct negotiations between Harvard and the community.

In September 1970, in anticipation of meeting with Harvard, the Riverside Planning Team proposed several potential sites for low-rent housing including the site of the former Riverside Press as well as the city-owned Corporal Burns Playground on Flagg Street. A study during the summer had shown that an average of only 15 kids used the playground per day. With plans to build a ‘tot lot’ in Putnam Gardens and a new playground at the long-anticipated King School, the Planning Team decided on affordable housing over recreation spaces. When they sat down at the negotiating table with Harvard’s representatives, Graham and the Planning Teams’s initial demand was for 150 units of “low cost, low rise” housing on this location. It had been the former “Treelands” garden center.

In early 1971, after months of negotiation, Harvard acquired 1.6 acres of land on Howard Street to build low-income housing to meet the demands of the Riverside Planning Team. The Treelands site wouldn’t be developed for another 30 years. In 2002, Harvard planned an art museum for this location but struck another compromise with Riverside and the city. In exchange for building 328 units of student and faculty housing on Cowperthwaite (near Mather and Louis’ Superette), this land was given to Cambridge to build a park. An industrial space (visible from this park, across River Street on Blackstone Street) near the former Cambridge Electric Light Company was converted to 30 units of affordable housing in 2004.

Stop 9: Continue along Memorial Drive (or walk along Blackstone St and through Riverside Press Park) to the former Polaroid Headquarters at 784 Memorial Drive.

In October of 1970, two employees of the Polaroid Corporation, Caroline Hunter and Ken Williams discovered an identification badge with the words “Department of the Mines, Union of South Africa.” It was an advertising mock-up using another Black colleague’s photo. According to Hunter, all they knew about South Africa was it was “a bad place for black people.” They soon discovered that the apartheid regime was using Polaroid’s machinery to produce the photos for passbooks that Black South Africans were forced to carry at all times as a means of enforcing segregation and controlling of the movement of the Black majority.

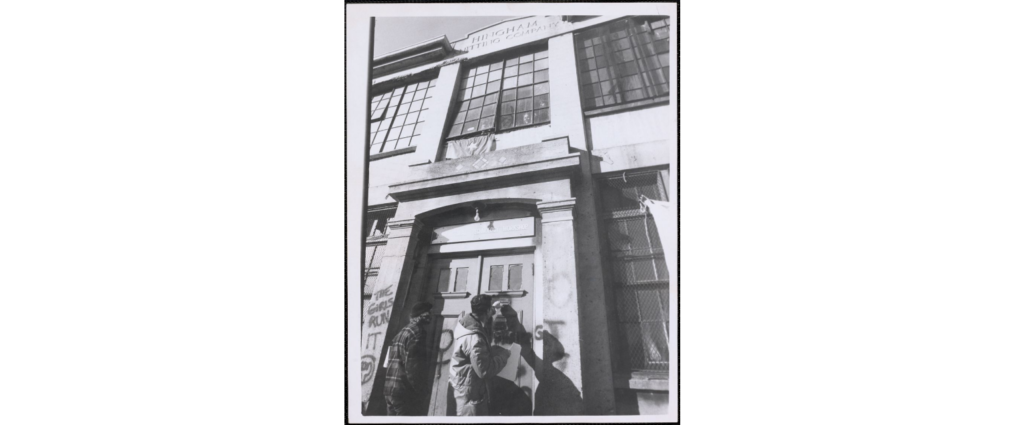

(Courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society)

Within days, Hunter and Williams mimeographed provocative fliers (see image) that said “Polaroid imprisons black people in sixty seconds” and “Did Polaroid shoot every South African black?” They plastered company bulletin boards in Technology Square with leaflets and formed the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (P.R.W.M.). Their demands were that Polaroid: 1) “disengage” from South Africa, 2) denounce apartheid (in both the US and South Africa), and 3) invest any profits in liberation movements.

Initially, Polaroid denied any involvement, claiming Frank & Hersch, their distributor, was solely responsible for sales of Polaroid products in South Africa. Declaring that they were a company with a conscience, they increased wages and provided scholarships for the Black workers at their South African distributorship. Williams and Hunter argued higher wages and scholarships were not radical enough to address issues of racism, genocide, and land and resource redistribution. They created P.A.N.I.C.–“Polaroid workers Against National Identity Cards”–and agitated for a boycott of Polaroid and a wider boycott of South Africa as the way to bring down the apartheid regime. When Hunter testified before the US Congress and the United Nations, she was suspended without pay (and subsequently fired) for “actions detrimental to the company.”

Seven years later, in 1977, Polaroid finally severed business ties in South Africa, paving the way for other corporations to do the same. Known as Divestment, this movement weakened the South African government in the 1980s. It would take another decade before a sanctions bill was passed in Congress. When Nelson Mandela was released from prison, he visited Boston in June 1990 to give thanks to the people who launched divestment. Hunter visited South Africa in February 1994 to celebrate the country’s first democratic elections.

Stop 10: Turn on left onto Pleasant Street and take the first right into the Trader Joe’s parking lot and look for the mural on the back of Microcenter.

Bernie LaCasse’s 1980 mural shows a diverse crowd of fist-shaking citizens confronting a man in a bulldozer. It represents the neighborhood activists who fought the inner beltway, a proposed 8-lane highway through Cambridgeport. In 1966, when Cambridge lost the power to veto the project, activists coalesced into a group called Save Our City. Save our City plastered the neighborhood with yard signs saying “Cambridge is a city, not a highway.” Between 1965 and 1970, they built a diverse coalition of citizens, city and state representatives, and local churches to confront and—in 1971—defeat the powerful interests behind the highway project.

Originally, the Master Highway Plan of 1948 proposed that the highway traverse Cambridge at either River Street or along Brookline and Elm Streets. When the city greenlighted the Houghton Urban Renewal Project, it eliminated the River Street route and the Brookline-Elm corridor became the focus. It was estimated that 1500 homes and 100 businesses along Brookline and Elm Streets would be destroyed to pave the way for the beltway. At the time, Cambridgeport was a mixed (integrated) neighborhood with Greek, Irish, French, Italian, and Black working class and middle-income families. It also had a large but declining industrial area.

Anstis “Ansti” Benfield, a Boston University student writing her thesis on the inner beltway, emerged as a leader. Together with Bill Ackerley, a former labor organizer whose Lopez Street home was in the path of the highway, she led rallies and marches and pushed for debate in the halls of power.

On February 27, 1966, Benfield led a march through the neighborhood and down Massachusetts Avenue to City Hall, with 250 protesters singing songs and carrying signs that said “Save our Homes.” Benfield presented a petition signed by residents to City Councilor Walter Sullivan labeling the current plan “inhumane” and demanding the highway be relocated to Albany and Portland Streets, which would displace fewer families. With a theatrical flourish, Benfield nailed the demands to the door of City Hall like a modern-day Martin Luther. The press snapped her photo with her two year-old daughter Rebecca strapped to her back. The City Council and Congressman Tip O’Neill threw their support into opposing the beltway.

Simplex Wire Company and NECCO opposed the Albany-Portland route. When the Grand Junction railroad corridor was proposed as an alternative, MIT Chairman James Killian strongly opposed this route, holding that protecting MIT’s military and nuclear research should be the preeminent concern—the new highway route would endanger national security interests. Killian ignored the protestor’s requests to meet. Refusing to be ignored, Anstis Benfield and two other mothers walked over to MIT’s campus and sat down in the halls of an MIT office building. They picnicked indoors with their children, making peanut butter sandwiches. They were granted a meeting and, soon after this, Harvard and MIT offered $1 million to help house and relocate people due to the beltway construction.

In March 1966, resistance escalated with a letter-writing campaign to Washington, rallies, and a march to Boston’s City Hall as well as an official visit by city leaders to speak to Congress. The following year, in 1967, 100 residents including 25 children travelled overnight on two buses to Washington DC. Governor Volpe continued to support the beltway and it looked like the project would move forward; construction started in Somerville and Jamaica Plain and housing evictions in Roxbury were underway. But the tide was turning. At the 1969 “People Before Highways” rally at the Massachusetts State House, newly-elected Governor Frank Sargent announced an anti-highway stance in a speech sympathetic to the cause. In 1970, Sargent would call for a moratorium on new highway construction inside Route 128, and the focus shifted to expanding public transit (MBTA) including extending the Red Line. The citizens had united around a common cause and defeated Goliath.

Feb 26, 1966 (Courtesy Cambridge Historical Commission Inner Belt Scrapbook)

Stop 11: Walk across the Trader Joe’s Parking Lot and return to Central Square along Pleasant Street. Stop at 46 Pleasant Street which is just before the intersection with River Street.

As mentioned at Stop 7, during the occupation of 888 Memorial Drive in March of 1971, the activists were offered $5,000 toward the creation of a women’s center. The donor was an individual, Susan Lyman who, after getting married and having two children, decided—at age 25—to attend Radcliffe. She had her third child during her junior year, graduated in 1949, and later worked in fundraising for Radcliffe. Lyman recognized that money was an issue for women; as recently as 1970, a married woman needed permission from her husband to open a bank account. This $5,000 donation became the down payment for this building at 46 Pleasant Street. The Cambridge Women’s Center opened here in January, 1972.

The Women’s Center had radical roots in the Bread and Roses collective’s ideology of socialist feminism. In the summer of 1970, the women of Bread and Roses voted to create a women’s center that would provide childcare, health and legal services, and self-defense classes as well as a place for women to socialize and to reduce isolation. They looked for a building to occupy, believing that the struggle of taking over a building would “make their movement larger, more unified, and more powerful.” The shortlived occupation of 888 Memorial Drive (see Stop 7) had a festive atmosphere, with music, dances, dinners, a “lavender lounge” for gay women, women’s skills classes, and an event for children in the neighborhood that was a “terrific success” according to the Women’s Center’s first newsletter On Our Way.

The Women’s Educational Center (as it was originally known) was “committed to the philosophy that women, empowered by taking responsibility for their lives, are able to help themselves and effect change in their communities.” To this end, there was a focus on activism and education from the start. Twenty volunteers created The Women’s School to teach classes in topics such as anti-racism, auto mechanics, growing up female, lesbianism, Marxism, tenants rights, and international women’s struggles including population control in Latin America and women in China. In the 1970s, radical feminists increasingly recognized the intertwined nature of identity. Activists at the Women’s Center were active with other organizations like Cell 16 and the Daughters of Bilitis. Many of the activists at the Women’s Center were lesbians who “recognized the inherent heterosexism embedded in patriarchy.” Of course, not all women at the Women’s Center were activists and there were tensions between different interests.

The Women’s Center was at the forefront of what was known as the “Battered Women’s Movement” of the 1970s. Activists sought to end the shame, secrecy, and isolation experienced by women who were experiencing domestic abuse. At the time, battering was not illegal—domestic violence was viewed as a private matter and a moral failure in the woman. Victims were blamed as having either provoked the violence or desired it. A founding member of the women’s center and a survivor of domestic abuse, Betsy Warrior, created the Battered Women’s Directory Project—an annual compilation of resources (1975-1985) that also included analysis of male-pattern violence and templates for shelter procedures.

By meeting together and hearing each other’s stories at the Women’s Center, activists gained awareness that “violence against women was a tactic of patriarchal control and oppression.” They connected battering with how women were devalued in society. Betsy Warrior made the point that women stay in abusive relationships because they lack the means to escape. Lisa Leghorn, another early member of the Women’s Center agreed that changing women’s economic status was crucial to ending abuse. She argued “that until women’s work in the home is recognized as labor. . . we’re not going to have the corresponding social power that paid and recognized and respected work has.” Together they published The Houseworkers Handbook (1974) to argue for fundamental economic equity.

Increasingly, women connected battering to other women’s issues. They needed to change how police treated domestic violence, how the law and the courts viewed it, as well as providing shelter and resources for victims. The first battered women’s shelter on the east coast grew out of the work of Betsy Warrior at the Cambridge Women’s Center. In 1974, Chris Womendez and Cherie Jimenez—both of whom experienced domestic abuse—used their own welfare checks to shelter battered women in their shared home on Pearl Street, a few blocks from the Women’s Center. By the summer of 1976, 25 women and children were living in their house. Eventually, they opened Transition House in a secret location for the safety of the women.

In 1974, Barbara Smith, her sister Beverly Smith, and Demita Frazier founded the Combahee River Collective. Over a period of six years, hundreds of women attended their consciousness-raising sessions at the Cambridge Women’s Center, addressing concerns that included the abusive sterilization of Black and brown women, abortion rights, and domestic violence. Their famous 1978 statement declared “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

Stop 12: Conclusion of Tour. If you are hungry, turn left on River Street and walk back to support the (Black-owned) Coast Cafe; otherwise, turn right on River and return to Central Square.

Issues that inspired activism in the early 1970s in Cambridge—affordable housing and rent control to stem the tide of gentrification, women’s basic rights to equal pay for equal work, laws against domestic abuse, and access to abortion, and civil rights and police brutality—are still very relevant today. Instead of consciousness raising groups in living rooms and Black Panther meetings at the Cambridge Community Center, much of our activism today is on social media and with hashtags. We who grew up in the Riverside neighborhood need to carry on the legacy of these courageous women who spoke truth to power. I hope the stories of these women bring back memories to our elders and inspire a new generation of young women who will rise up and take to the streets in the name of justice and equity. There is still work to be done.

Annie M. Brown, Cambridge, 2020

Special thanks to: Diana Lempel, Founder, Our Riverside; Yvonne Gittens, Cambridge Community Center; Rochelle Ruthchild and the film-makers of Left on Pearl; Jessye Kass and Judy Norris, Cambridge Women’s Center; Emily Gonzalez, Cambridge Historical Commission; Kimm Topping, Cambridge Women’s Commission; Alyssa Pacy, Cambridge Room, Cambridge Public Library; Stephen Kaiser; Caroline Hunter; Tess Ewing; and Lee Brown and Larry Duberstein

Sources for Women Activists of Riverside

CAROLINE HUNTER’S ANTI-APARTHEID WORK AT POLAROID

Schachter, Aaron. “Polaroid Worker Who Protested Company’s Ties To Apartheid South Africa Reflects On Wayfair Walkout.” WGBH , WGBH, 30 June 2019, www.wgbh.org/news/local-news/2019/06/30/polaroid-worker-who-protested-companys-ties-to-apartheid-south-africa-reflects-on-wayfair-walkout.

“Caroline Hunter’s Biography.” The HistoryMakers, The HistoryMakers, 2014, (oral history taken August 9, 2014) https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/caroline-hunter

Martin, Phillip. “How A Cambridge Woman’s Campaign Against Polaroid Weakened Apartheid.” WGBH News, WGBH, 9 Jan. 2016, www.wgbh.org/news/post/how-cambridge-womans-campaign-against-polaroid-weakened-apartheid.

Levey, Robert. “Blacks at Polaroid Oppose Sales to S. Africa.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Oct 18 1970, p. 64. ProQuest. Web. 21 Aug. 2020 .

“What is Polaroid Doing in South Africa?” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Nov 25 1970, p. 7. ProQuest. Web. 21 Aug. 2020 .

“Polaroid Suspends Girl Activist.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Feb 11 1971, p. 3. ProQuest. Web. 22 Aug. 2020 .

Taylor, David. “75 Protest Firing at Polaroid Group Demands Product Boycott.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Feb 25 1971, p. 3. ProQuest. Web. 22 Aug. 2020 .

McCabe, Bruce. “Polaroid Renews S. Africa Program.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Dec 31 1971, p. 2. ProQuest. Web. 22 Aug. 2020 .

Lewis, Diane E. “PIONEERS RECALL DIVESTMENT BATTLE: [THIRD EDITION].” Boston Globe (pre-1997 Fulltext), Feb 16 1990, p. 1. ProQuest. Web. 19 Aug. 2020 .

William, Henry 3. “Erased Tape Causes Flap.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Jan 16 1978, p. 23. ProQuest. Web. 21 Aug. 2020 .

Williams, Ken, and Caroline Hunter. “LETTERS TO THE EDITOR: THE POLAROID ‘EXPERIMENT’ IN SOUTH AFRICA.” Boston Globe (1960-1988), Aug 23 1973, p. 22. ProQuest. Web. 21 Aug. 2020.

“African Liberation Committee Film” Say Brother Program Number 306 http://openvault.wgbh.org/catalog/V_C79BD18CC4A8438E9AA5F976D8A36714

Democracy Now. “Polaroid & Apartheid: Inside the Beginnings of the Boycott, Divestment Movement Against South Africa” Youtube, Dec 13, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXVSdqnCl5k.

WOMEN’S TAKEOVER AT 888 MEMORIAL DRIVE AND THE WOMEN’S CENTER

888 Memorial Drive

Bear, Carson. “The Historic Harvard Campus Building That Once Housed a Feminist Takeover: National Trust for Historic Preservation.” The Historic Harvard Campus Building That Once Housed a Feminist Takeover | National Trust for Historic Preservation, 19 Jan. 2018, savingplaces.org/stories/the-historic-harvard-campus-building-that-once-housed-a-feminist-takeover.

Freedman, Judith, and Crimson Staff. “Bust Likely at Women’s Center: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson, 13 Mar. 1971, www.thecrimson.com/article/1971/3/13/bust-likely-at-womens-center-pas/.

Rivo, Susie “Left on Pearl” 2016 (film and website) https://leftonpearl.org/

“Harvard Clears Site At 888 Mem Drive: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson, 3 Nov. 1971, www.thecrimson.com/article/1971/11/4/harvard-clears-site-at-888-mem/.

Monroe, Rev. Irene. “A Feminist Takeover Remembered: 888 Memorial Drive.” San Diego Gay and Lesbian News, 17 Mar. 2016, sdlgbtn.com/commentary/2016/03/17/feminist-takeover-remembered-888-memorial-drive.

Patkin, Abby. “Brookline Resident Reflects on 1971 Takeover of Cambridge Building.” Cambridge Chronicle & Tab, 19 Mar. 2019, cambridge.wickedlocal.com/news/20190318/brookline-resident-reflects-on-1971-takeover-of-cambridge-building.

Sasseen, Rhian. “The Girls Run It: Left on Pearl and the 888 Memorial Drive Takeover.” The Toast, 2014, the-toast.net/2014/01/13/girls-run-left-pearl-888-memorial-drive-takeover/.

Schlesinger, Libby, director. International Women’s Day March and the Occupation of 888 Memorial Drive, Personal Film Footage Shot on 8 Mm by Alice Maxfield, 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=GU3sk4sg0a4.

Women’s Center

Battered Women’s Directory Project Records, 1975-1985; item description, dates. MC 816, folder #. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/sch00439/catalog Accessed November 01, 2020

Betsy Warrior Papers, 1966-1996; item description, dates. MC 843, folder #. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/sch01511/catalog Accessed November 01, 2020

Bowers, Debra, director. Beyond the Shelter Door. YouTube, Colorado Public Television (PBS 12), 1986, www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4Ovpsa1caM&list=PLM-uZluxsDc3HuogE4kABT1-cS8dXxOM1.

Leghorn, Lisa and Betsy Warrior The Houseworker’s Handbook Cambridge Women’s Center. 1974

Leghorn, Lisa and Katherine Parker. Woman’s Worth Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. Boston. 1981

MacFarquhar, Larissa. “The Radical Transformations of a Battered Women’s Shelter” New Yorker August 19, 2019 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/19/the-radical-transformations-of-a-battered-womens-shelter

Marquard, Bryan. “Susan Storey Lyman, 97, chair of Radcliffe Board of Trustees” Boston Globe February 25, 2017.

Matchan, Linda, “Shelters from the Storm” Boston Globe June 15, 2010 http://archive.boston.com/lifestyle/family/articles/2010/06/15/cherie_jimenez_has_turned_her_life_around_from_drugs_prostitution_and_abusive_relationships_and_is_helping_other_women_to_do_it_too/

Rodell Susanna “Susan Lyman: A Portrait” Harvard Crimson June 7, 1979

“Tess Ewing.” Cambridge Women’s Heritage Project Database, E, Cambridge Women’s Commission, www2.cambridgema.gov/Historic/CWHP/bios_e.html

Tuohy, Patricia. “Confronting Violence: Generations of Reformers.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 9 Sept. 2020, www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/confrontingviolence/exhibition1.html

Women’s Educational Center (Cambridge, Mass.) records, M047. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/831 Accessed November 01, 2020.

Women’s School (Cambridge, Mass.) records, M023. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/807 Accessed October 31, 2020.

SAUNDRA GRAHAM AND THE FIGHT FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Bethell, John T.. Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century. United Kingdom, Harvard University Press, 1998.

Cambridge Planning Board (report) “Thirteen Neighborhoods: One City” 1953 https://www.cambridgema.gov/~/media/files/cdd/planning/neighborhoods/neigh_onecity.pdf

“Corporation Orders Plans For Housing Development: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson, Harvard Crimson, 16 Feb. 1971, www.thecrimson.com/article/1971/2/16/corporation-orders-plans-for-housing-development/.

“Council Settles Houghton School Relocation Fight” Harvard Crimson June 12, 1968 https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1968/6/12/council-settles-houghton-school-relocation-fight/

Cunningham, Bill “Which People’s Republic?” © April, June 1999 Seven Cats Press http://rwinters.com/docs/which_peoples_republic.htm

Cunningham, Bill “When Public Housing Came to Town” Alliance of Cambridge Tenants Summer 2012.

Dorgan, Lauren R. “The Battle Next Door: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News |The Harvard Crimson, 12 Apr. 2002, www.thecrimson.com/article/2002/4/12/the-battle-next-door-standing-before/

Gross, Terry, “A ‘Forgotten History’ Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America” Fresh Air NPR May 3, 2017

Joanne Pelham (left) and Saundra Graham (right), Police Brutality Hearings, Cambridge City Council, January 1971, Olive Pierce Photographs, 1963-2014, 045, [Box6, Folder 3], Cambridge Room, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections.

Landau, M David. “Riverside Group Opposes Harvard’s Housing Plans: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson, 23 Sept. 1970, www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/9/23/riverside-group-opposes-harvards-housing-plans/.

Nelson, Robert K., LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed October 23, 2020, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/Cambridge

“Riverside Rezoned.” Harvard Magazine, 1 Jan. 2004, harvardmagazine.com/2004/01/riverside-rezoned.html.

“Saundra Graham: News: The Harvard Crimson.” News | The Harvard Crimson, Harvard Crimson, 1971, www.thecrimson.com/article/1971/10/29/saundra-graham-ptheres-only-one-problem/.

Cambridge Chronicle:

- “Claims Houghton Renewal Plans To Hit Colored Residents Hardest” 24 August 1961

- “DAN COULDN’T DO BETTER” 24 February 1955

- “Houghton Area Problems Aired By Riverside” March 9 1961 p 17

- “Houghton Area Renewal Funds Get Green Light” 11 August 1960 page 1, 7

- “Houghton School Area Slated For Urban Renewal Project” 14 July 1960 page 1, 7

- “Letter to the Editor, 6 July 1961 p 1 and 6

- “Discrimination in Housing Seen as Basic Problem In Houghton Renewal Aims” October 5 1961 p 10

- “Public Invited To Discuss Houghton Renewal Plans”, 22 June 1961 Front Page with map

- “Riverside Neighborhood 7 Seeks Federal Aid”, 20 June 1957 page 1

- “Riverside Votes Tonight on Plans For a Tot Lot” Aug 20 1970

- “U.S. Halts Spending Of Planning Funds On Urban Renewal”, 21 June 1962 pge 1-2

- “Western Ave. Housing Survey Organized By A Technology Dean Cambridge”, 8 February 1940

- “Whitlock Talks About Houghton Area Planning”, 25 May 1961

ANSTIS BENFIELD AND THE FIGHT AGAINST THE INNER BELTWAY

Clippings: Inner Belt Activities (Inner Belt Scrapbook) Cambridge Historical Commission, Posted October 2, 2017 https://www.flickr.com/photos/cambridgehistoricalcommission/36747639894/in/album-72157687092912054/

“Anti-Beltway Rally Here on Sunday,” Cambridge Chronicle, March 31, 1966

“Editorials,” Cambridge Chronicle and Sun, March 3, 1966. Page 8

“Housing Aid Offered for ‘Belt’ Refugees,” Morning Union Leader, March24, 1966.

“Mail Protest Planned,” Christian Science Monitor, March 21, 1966.

“Nail Belt Protest on the Wall,” Boston Sunday Advertiser, February 27, 1966.

“Opposition Grows to Brookline-Elm Inner Belt Route” Cambridge Chronicle Dec 9, 1965. Page 1

Plotkin, A.S. Air Rights Idea May Save Face,” Sunday Boston Globe, September 17, 1967

Stewart, Richard, “Belt Foes Rap Volpe in Capitol,” Boston Evening Globe, May 24, 1967

Woodman, Wendell, “Better-Late-Than-Never Inner Belt is Underway” Malden News, May 19, 1967

“Francis Sargent Promises Review Of the Inner Belt” Harvard Crimson, January 27, 1969

Inner belt route. 12 Apr 1966. Web. 02 Nov 2020. <https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/wd377684g>

Kaiser, Stephen. “Inner Belt Report Step One” Cambridge Historical Commission October 14, 2017 https://www.cambridgema.gov/-/media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/innerbelt_kaiser.pdf

Kaiser, Stephen. “A Bit of History : The Odd Couple of Citizen Activism Fights the Massive Highway Plan” CCTV 12 September 2013 https://www.cctvcambridge.org/node/190060

Reyes, Max. “Crowd commemorates 1969 protest that halted Inner Belt road project” Boston Globe 2019 https://edition.pagesuite.com/popovers/dynamic_article_popover.aspx?appid=1165&artguid=830c4a42-9473-413b-abf0-a8865c29d2ce

Samuelson, Robert J. “Cambridge and the Inner Belt Highway: Some Problems are Simply Insoluble” Harvard Crimson June 2, 1967 https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1967/6/2/cambridge-and-the-inner-belt-highway/

Sullivan, Charles. “Radical Events In Cambridge” Cambridge Historical Commission (presentation) https://www.cambridgema.gov/-/media/Files/historicalcommission/pdf/slideshows/ss_radical.pdf

This tour was made possible through funding from the Cambridge Heritage Trust.