New England Glass and the history of glassmaking in East Cambridge

By Beth Folsom, 2025

The Cambridge papers announced in April 1850 that the New England Glass Co. was building an enormous chimney for its glassworks site on North Street in East Cambridge. With a 30-square-foot base, the chimney would climb to 240 feet, “20 feet higher than the Bunker Hill Monument!” This construction was a further sign of progress and growth in what was already the neighborhood’s largest industry – one of the first to take root in the burgeoning manufacturing sector of 19th century East Cambridge.

Although the glass industry was an early presence in the newly developing East Cambridge of the 1810s, glassmaking as a craft was present in the American colonies from the beginnings of British settlement. In 1608, several men in the Jamestown colony tried to establish a glassworks, but their efforts were soon overshadowed by the colonists’ more pressing basic needs for survival. From 1621 to 1625, Capt. John Smith built and oversaw a second glass house, but again, the desire for decorative glass items came a distant second to the political, social and economic challenges facing the colony.

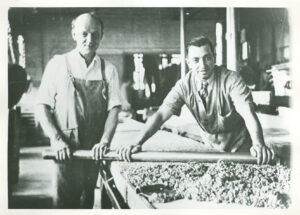

In the late 1630s and early 1640s, glassworks in Salem were producing glass “necessities” such as window panes and bottles, but this venture too was short-lived, and most glass was imported to the colonies from Europe through the middle of the 18th century. Beginning in the 1730s, Dutch and German immigrants established glass factories in New York and New Jersey, marking the birth of a significant domestic glass industry. Because glassmaking was a cultivated craft in Northern and Western Europe, these early glass houses brought over highly skilled artisans to work in their colonial factories and to train a domestic workforce in the craft.

The firm of Whalley and Hunnewell opened a glassworks in Boston in 1787 that later became the Boston Window Glass Co. Another, larger factory was established in South Boston in 1811, but the War of 1812 (during which the United States was at war with England) made domestic glassblowers hard to come by and impeded trans-Atlantic travel, thereby limiting the company’s ability to bring skilled workers from Britain.

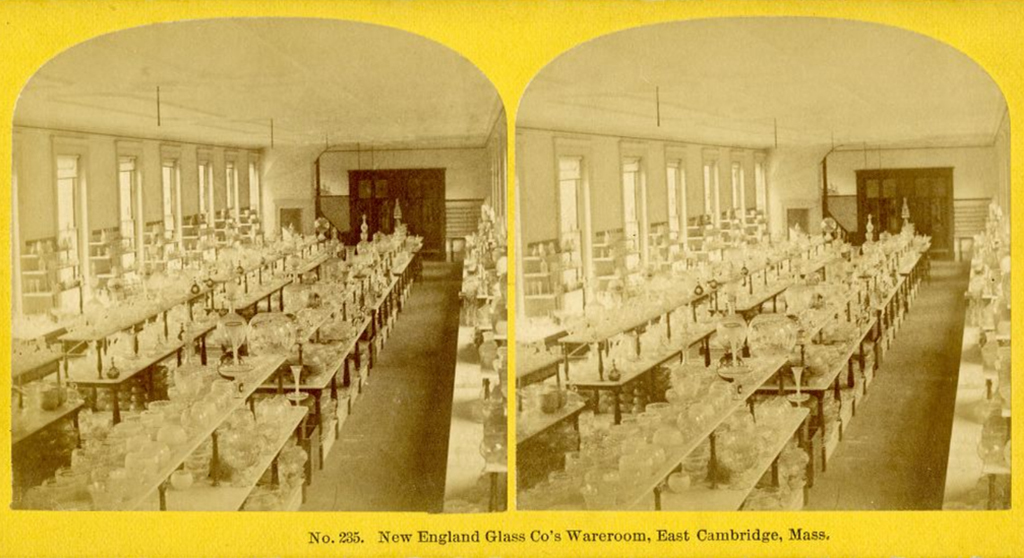

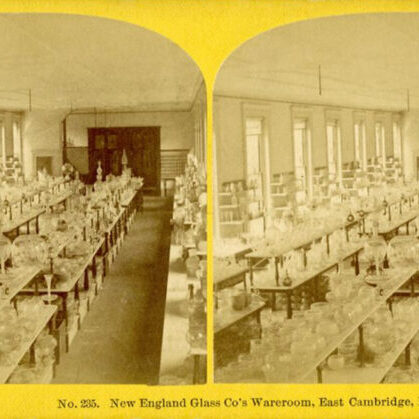

The Porcelain and Glass Manufacturing Co. was established in East Cambridge in 1811, and in 1817 came under the ownership of four prominent East Cambridge men – Amos Binney, Daniel Hastings, Deming Jarves and Edmund Munroe – who renamed it New England Glass. By midcentury, it was the largest tax-paying “resident” entity in East Cambridge, second only to the “nonresident” taxpayers of the Boston & Lowell Railroad. By this time, the glassworks was making many decorative items as well as its original utilitarian glassware, and the Cambridge newspapers announced proudly its many awards at local and national fairs and exhibitions. An 1866 feature in the Cambridge Chronicle declared that the company’s glassware “is prized equally for its uses in the kitchen and the pantry, and the adornment of the drawing room and boudoir, and it furnishes the choicest ornaments for the festive board.”

By the 1870s, the company had become such an integral part of the East Cambridge neighborhood that it claimed a whole section of the city’s centennial parade in 1875, which celebrated the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s 1775 arrival in Cambridge to take command of the Continental Army. The Chronicle called it “one of the most elaborate and successful displays in the procession:

“The first in order was a drum corps, followed by the Coveney Cadets of Cambridge, Capt. James Coffee, 45 men. Each man had in the muzzle of his rifle a small blown glass globe, red, white, and blue being distributed to make a pretty contrast. Then came a four-horse barouche with the agent and managers of the company. This was followed by a four-horse team containing a miniature blast furnace, showing the process of glass manufacture. A number of men were engaged in blowing their glass globes, which were thrown among the crowd by little boys. Then came 75 glass makers and 60 boys on foot, all carrying specimens of glass work.”

The following decade would see the company’s fortunes fall, rise and fall again. The second half of the 1870s brought a rise in worker strikes around the country as laborers sought better hours, safer working conditions and a greater share of the fortunes that had enriched their employers – a trend from which East Cambridge’s glass workers were not exempt. There was also a downturn in the glass market at that time, and the company announced its impending closing in 1877.

William Libby, who had been an executive with the company, agreed to take it over and, for a decade, it continued to manufacture in East Cambridge before finally moving to Toledo, Ohio, in 1888 to take advantage of cheaper land and labor. A number of workers departed for Ohio with the company, as there were limited options for them to ply their trade in the Cambridge area.

The Cambridge Tribune reported in 1889 that several had returned, “not because they disliked Toledo, but because they liked East Cambridge more.”

This article originally appeared in Cambridge Day.