How the highlighter was invented in Cambridge by Carter’s Ink, an innovator back to the 1800s

By Michael Kuchta, 2025

History Cambridge is spending 2025 focused on the history of East Cambridge, including the people who have inhabited the neighborhood, the occupations that employed them and the buildings, streets and public places they created. This is the story of a company that was based in East Cambridge for decades, Carter’s Ink.

In the 1950s, Cambridge, like many Northeastern cities, began to lose the manufacturing businesses that had sustained its growth over the previous century. Important local employers such as meatpackers, candy makers and soap factories looked to take advantage of abundant land in the suburbs and cheaper labor in other states, abandoning often-outdated facilities here. This was especially true in East Cambridge, where many factories, wharves and warehouses had been built on former marshlands in the late 1800s. The companies that remained, including Carter’s Ink, had to innovate to survive.

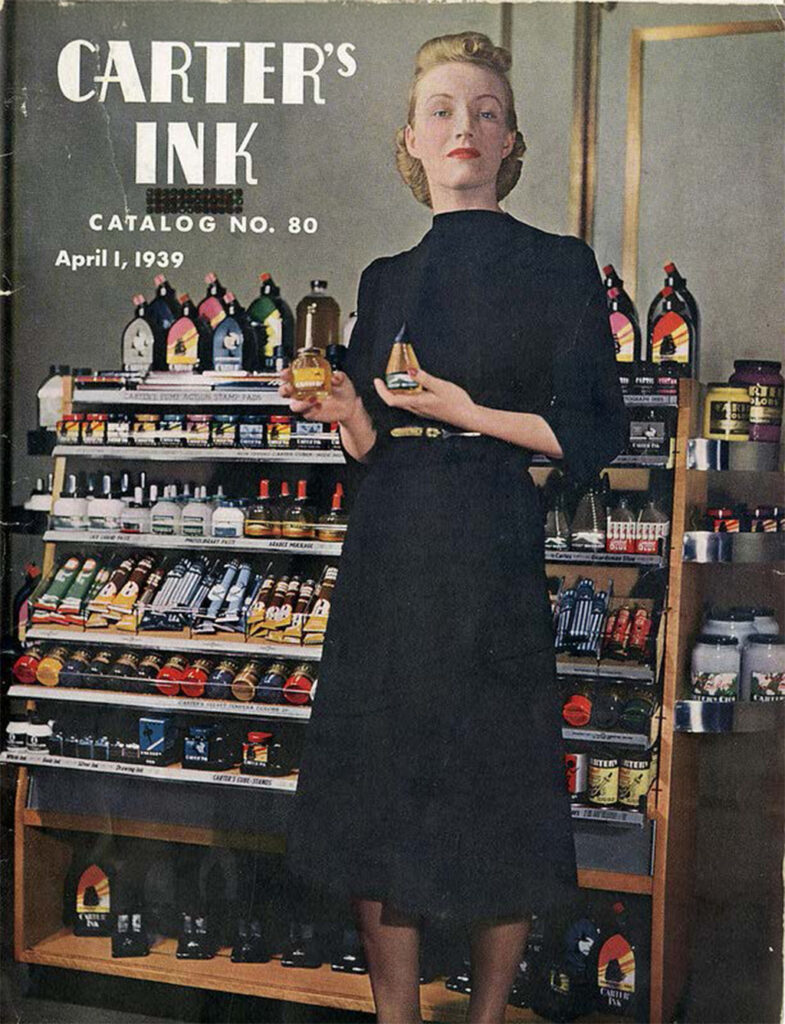

Started in Boston in 1858, Carter’s moved to East Cambridge in 1910, where it built a factory on First Street facing the Charles River. The company had long since learned the importance of product innovation. In the 1860s, Carter’s thrived because it developed a competitive advantage: its Combined Writing and Copying Ink could be used to make multiple copies of a document – long before the invention of the photocopy machine or even carbon paper. John W. Carter, cousin to the three brothers who founded the company, revived Carter’s in 1872 after a devastating fire by hiring a skilled chemist to develop new inks. By 1884 the company was manufacturing nearly 5 million bottles of ink a year. Carter’s added library paste, ink eradicator and new ink colors to its product line, and, as typewriters became popular, carbon paper and ribbons. In its East Cambridge plant, Carter’s installed automated equipment for filling, capping and labeling bottles.

In the 1920s, Carter’s Ink gained local goodwill through its civic engagement. It participated in the Cambridge Industrial Athletic League, sponsoring baseball and bowling teams. In 1926, the company topped its First Street building with an electric clock, which became a landmark on the riverfront. By 1930, Carter’s Ink employed more than 500 people and claimed to be the largest ink manufacturer in the United States.

The company remained profitable through World War II and continued to expand its East Cambridge operations in the 1950s. In March 1958, the company introduced a line of felt-tipped markers called “Marks-A-Lot” that proved instantly successful. Carter’s sold Marks-A-Lot in grocery and variety stores, producing them in bright colors and displaying them in easy-to-see clear plastic blister packs. They were a particular hit with children, but parents didn’t appreciate the fact that they left permanent marks on walls, clothes and furniture. Mothers wrote to the company begging for washable versions. In response, Carter’s chemists formulated inks made with water rather than oil or solvents and sold them as “Draws-A-Lot.” The company expanded its Cambridge manufacturing plant to meet demand for the new markers.

In 1959, Carter’s hired Francis Honn, an industrial chemist then working for 3M in Minnesota. Honn was responsible for quality control, and he often grabbed samples from the assembly line. One day, he tested a translucent yellow marker by using it across a page of type. “The black type literally jumped out at me,” Honn recalled in an unpublished memoir nearly a half-century later. “Here was a better way of highlighting key printed words than underlining!”

Honn instructed the company’s sales staff to send out letters to customers who had complained or asked questions, writing over a few key words, like “refund” and “free sample,” with yellow ink. At the bottom of the page, Honn added a sentence: “Wonder where the yellow came from? Carter’s Reading Hi-Liter” – riffing on a popular toothpaste advertisement that claimed “You’ll wonder where the yellow went when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent.” Within a week, Honn wrote, “letters came pouring in asking where they might buy this wonderful product.” Honn received permission from the company’s executive board to sell the Reading Hi-Liter in a test market. Company president Nate Hubley suggested school bookstores, which already carried Carter’s products. The marketing department designed an eye-catching blister pack, pairing a Draws-A-Lot marker with a Hi-Liter.

As Honn remembered it, the company had to invest only $3.50 to market the new product, creating a rubber plate to print “Reading Hi-Liter” on their existing yellow markers. Honn and his team didn’t so much “invent” the highlighter as recognize its usefulness and find ways to sell it to the world.

Highlighting markers have changed the way that readers take notes, editors revise texts and students study for exams. Highlighting markers now come in pink, green, orange and blue in addition to the original yellow. (“Yellow is still the only good color,” Honn argued in his 2009 memoir, basing his assessment on his own perceptions and on the theory, which he’d learned at 3M, that yellow and black offer more contrast to the eye than other color combinations.) In 2012, The New York Times reported that 85 percent of markers sold were either yellow or pink.

Honn left Carter’s Ink by 1970. After a long career as a chemist and company executive, in which he was granted more than 25 patents, Honn retired in 1988 and died in 2016 at age 94.

As a sign of its ubiquity, the highlighting marker even has its own Wikipedia entry. The word “highlight” has become a verb. The yellow felt-tipped marker has also transitioned to the digital realm, used as an icon for highlighting text in programs such as Google Docs and Microsoft Word. In a 2016 interview with the alumni magazine of John Carroll University, Honn said, “The fact that something so simple could still have such an impact today makes me happy.”

Unfortunately, the success of the Hi-Liter was not enough to ensure Carter’s local presence. The company opened a plant in Tennessee in 1965 and shifted manufacturing to the lower-wage state. Its East Cambridge workforce went on strike that year, possibly as a response to the move. In 1966, Carter’s Ink opened another plant, this time in North Carolina, and a year later only the company’s administrative and research staff remained in Cambridge.

In 1975, Carter’s Ink reported sales of just $20 million, not enough to compete with larger firms in the office products industry. The following year it was acquired by Dennison Manufacturing of Framingham, an office supply and label maker more than 10 times its size. Under Dennison’s ownership, Carter’s remaining operations were moved out of East Cambridge, though the Carter’s name remains even today on packages of ink, markers and stamp pads.

Michael Kuchta is a volunteer and board member with History Cambridge. This article contains material originally developed for “Born in Cambridge; 400 Years of Ideas and Innovators,” co-written by Kuchta and published by the MIT Press in 2022.

This article originally appeared in Cambridge Day.