A Brief History of Zoning in Cambridge

By Doug Brown, 2016

Just as we have a place for everything in a well-ordered home, so we should have a place for everything in a well-regulated town. What would we think of a housewife who insisted on keeping her gas range in the parlor and her piano in the kitchen?

–Cambridge Tribune, March 8, 1919

In 1919, no city understood this better than Cambridge, as its booming factories produced both pianos for the parlor and boilers for the basement. Cambridge provided meat for the freezer, soap for the laundry, cars for the garage, and candy for the children. Rubber, wire, steel, ink, asphalt, chemicals, machine parts, biscuits, books, radios, and furniture poured

from its factories in an endless assault on the senses.

Of course, Cambridge had been making everything from bricks to glass to ice for years, but as it approached a peak population of 120,000 in 1925, the prospect of, as one commentator put it, “gas tanks next to parks, garages next to schools, boiler shops next to hospitals” strained the City’s limited geography. Depending on wind direction, the smells were enough to cloud the heads and turn the stomachs of most citizens.

Cambridge wasn’t unique. Beginning in the 1880s, most large cities created health and building codes in response to growing concerns of disease, fire, and overcrowding. Indeed, savvy landowners often employed deed restrictions to limit the uses of their subdivided land and protect values. In Cambridgeport, for example, the trades the Dana family prohibited in its developments included butcher, currier, tanner, varnish maker, ink maker, tallow chandler, soap boiler, brewer, distiller, sugar baker, dyer, tinman, working brazier, founder, smith, and brickmaker.

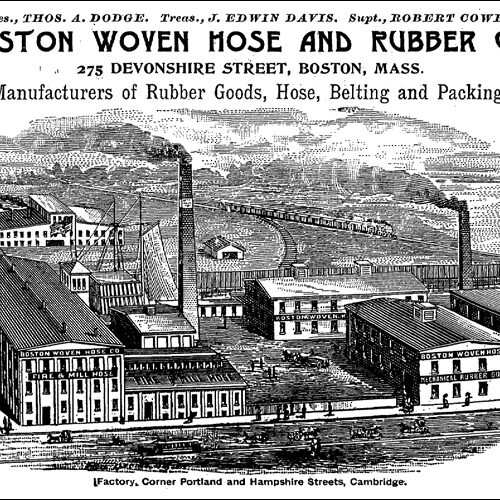

Even so, readers of The Jungle would have felt right at home in turn-of-the-century Cambridge, with its slaughterhouses and rendering plant employing thousands. Lever Brothers built a soap plant on the site of what is now Technology Square, and the Boston Woven Hose Company, producer of rubber products, installed itself on Broadway, just north of MIT’s new campus. Both brought unwelcome olfactory experiences to the neighborhood.

Cambridge began discussing new rules immediately following World War I, and hearings began in 1921. In 1924, an ordinance was approved that was modeled on the Euclidean zoning method, so named because a similar

system first appeared in Euclid, Ohio. The new code divided Cambridge into Residential, Business, and Unrestricted districts, each with four height limits ranging from 40 to 100 feet. In effect, the City was overlaid with 12 height and use combinations. It restricted “industries emitting noxious

odors, dust, smoke, gas, or noise” to specific zones within the City.

Newspapers of the day were quick to celebrate the progress. The Cambridge Tribune noted that “The whole purpose of zoning is to encourage the erection of the right building in the right place.” Henceforth, a Board of Zoning Appeal would decide what was right and what was not. Of course, no sooner was the ordinance passed than people began attacking it. In fact, much of modern U.S. zoning law stems from a single legal challenge to Cambridge’s rules. In 1924, Saul Nectow owned several acres of land on the corner of Brookline and Henry streets, next to the Ford Motor plant.

Cambridge had zoned a portion of this land as residential, even though it was surrounded by lots designated for industrial use. Mr. Nectow objected and, after an unsuccessful appeal to the City Council, he sued, claiming that he was unable to erect a commercial building or sell the land to a buyer because of this change.

In a previous case, the Supreme Court had ruled zoning constitutional as long as it provided a clear public benefit. “A nuisance may merely be a right thing in the wrong place,” the Court ruled, “like a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.” But in the Nectow case, the Court placed limits on these powers. In its opinion, the Court sided with Mr. Nectow, saying that “[a zoning restriction] cannot be imposed if it does not bear a substantial relation to the public health, safety, morals or general welfare.” Where the prior case established the right to enforce zoning, the Cambridge

case would limit its reach.

Times change, and so do residents’ concerns. In the 1930s, residents worried about the proliferation of gas stations. By the 1940s, it was large apartment buildings. Sometimes what was once decried is now embraced. A century ago, the Cambridge Chronicle reported that “people living in the Fayerweather Street section are much stirred up over the commercializing of that section by the addition of a number of unsightly one-story store buildings.” Today, the shops along Huron Avenue are considered neighborhood treasures, and Huron Village is protected by especially restrictive zoning that effectively limits building heights to a single story.

Such changing concerns led to major rewrites of the zoning rules in 1943, 1961, 1977, and 2000. Less and less do we need protection from big, dirty factories—those have all been shipped overseas—and in any case today’s zoning outlaws most heavy industries anywhere in the city: Acid manufacture, glue making, explosives, refining operations, trash incineration, smelting, and meatpacking are all expressly prohibited. Now, the top 25 Cambridge firms employ more than 50,000 workers, and most of those businesses (higher education, biotech, healthcare, software, and R&D) produce no physical product at all. More employees work for Whole Foods in Cambridge today (443) than for the entire city government of 1885 (406). (The City now employs more than 4,000 people.)

This year, Cambridge began yet another review of its zoning code, an effort known as Envision Cambridge. We now seek to reclaim former industrial land for new uses: housing, job creation, parks and open space, and mixed-use retail. Instead of distantly separated uses and the embrace of the car

culture, residents now seek enhanced mobility and places to live, work, shop, and play close to one another. Zoning will once more need to evolve if it is to remain relevant to our lives and supportive of our aspirations, both as individuals and as a city.