Cambridge Through the Pages

By Lucy Caplan, 2013

Did you know that Cambridge has been home to a mad scientist who can revive the dead, a teenager who met with George Washington, and a man who can see into his own future? Across the centuries, Cambridge has inspired writers of fiction and poetry as an ideal setting for their literary creations. This tour steps into the fictional worlds that these writers have imagined.

Introduction

One could say there are as many books about Cambridge as there are ways to write a book about Cambridge. This tour explores the richness and variety of that work.

It begins with a poem written over 200 years ago and concludes with a novel published in the early 2000s. In between, it offers the voices of men and women, of New Englanders and international immigrants, of teenage poets and elderly novelists. Some of the featured authors offer vivid, unsentimental accounts: windows into the city’s history. Others cross into more fantastical territory, imagining Cambridge as a setting for magic and time travel. And still others choose to delve into the lives of Cambridge individuals — their lowest points as well as their highlights and successes.

By including a broad selection of literary works, all linked by their common setting in Cambridge, this tour illuminates the many ways in which the city has served as a source of literary inspiration.

You may also download the tour here.

Stop 1: Phillis Wheatley: “To His Excellency General Washington” (1775): 105 Brattle Street

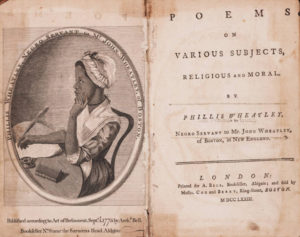

Born in West Africa in 1753 and sold into slavery in Boston at a young age, Phillis Wheatley rose to literary prominence while still a teenager and gained fame as a poet throughout the transatlantic world. Upon her arrival in Boston, she was purchased by the affluent Wheatley family, who named her Phillis after the ship that had transported her to America. Though Phillis unquestionably maintained the status of a slave within the Wheatley family, she did have access to an education, which was highly unusual. The Wheatleys’ eighteen-year-old daughter, Mary, taught Phillis how to read and write English, Latin and Greek, and also introduced her to the teachings of Christianity.

Wheatley’s prodigious talents first brought her widespread acclaim upon the publication of her poem on the death of the famed reverend George Whitefield, in 1770. Three years later, at the age of 20, Wheatley published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, thus securing her status as North America’s first published African-American poet and second published woman.

Revolution had been simmering in the American colonies throughout Wheatley’s lifetime, and war officially broke out with the firing of shots in Lexington and Concord in April 1775. By October of that year, Wheatley had written a poem commending General George Washington’s achievements — aptly titled “To His Excellency General Washington” — and sent a copy to his headquarters in Cambridge.

Washington was so taken with the poem that he considered publishing it, but was concerned that such an action might appear vain or conceited. Though he chose not to publish the poem, his cordial response to the young poet, some months later, expressed his admiration for Wheatley’s talent, and extended an invitation for a visit: “If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favoured by the Muses, and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations.”

Historians have not found any official record of the visit between Washington and Wheatley, but it likely took place at Washington’s headquarters during the spring of 1776.

“Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the Goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, Washington! Be thine.”

You can find more of Wheatley’s work on Google books.

Stop 2: William Dean Howells: Suburban Sketches (1872): 3 Berkeley Street

When William Dean Howells moved to his new home of Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1866, he became an eyewitness to the city’s rapid evolution. Cambridge was no longer the leafy, idyllic country retreat for residents of Boston that it once had been. Change swept the city as the establishment of factories, the construction of railroads, and the arrival of waves of Irish and Italian immigrants altered the city’s physical and social landscape.

The dramatic transformation he beheld made a profound impression on Howells, who had moved to Cambridge to take on both a Harvard professorship and an editorial position at the Atlantic Monthly. He was also a prolific writer of fiction, and he found found abundant inspiration in his new surroundings. In Suburban Sketches, published in the Atlantic Monthly as a series of installments in 1872, Howells described Cantabrigian life in vivid detail.

Suburban Sketches exemplifies the literary style of realism, of which Howells was a pioneer. Realism abandons the sentimentalism of earlier nineteenth-century literature and moves toward an emphasis on facts and details. The descriptions of Cambridge (thinly disguised in his text as “Charlesbridge”) in Suburban Sketches are technically fictional, but they offer an invaluable window into what life in the city was like circa 1870. Howells’s Cambridge was a city in transition: in his words, a “frontier.” From the front of his Berkeley Street house he could see horse-cars, ready to speed away to Boston. But if he walked for two minutes, he would enter a wild, untouched forest from which not a single house was visible.

The sonic environment juxtaposed mooing cows and singing birds with whistling locomotives and the pounding hammers of construction workers. Living in Old Cambridge, which retained much of its rural character long after urbanization in the Cambridgeport and East Cambridge neighborhoods, Howells had an especially striking perspective on the change occurring around him. Yet he maintained an understanding of the city as “perennially young and gay,” a thriving locale always in search of something new.

Then, indeed, Charlesbridge appeared to us a kind of Paradise. The wind blew all day from the southwest, and all day in the grove across the way the orioles sang to their nestlings. The butcher’s wagon rattled merrily up to our gate every morning; and if we had kept no other reckoning, we should have known it was Thursday by the grocer. We were living in the country with the conveniences and luxuries of the city about us…

Read Suburban Sketches at Google Books.

Stop 3: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “The Village Blacksmith” (1840): Plaque, 52 Brattle Street

The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow held a status in America’s cultural life that is unparalleled today. Widely regarded during his lifetime as the country’s most distinguished poet, he was a revered national figure. Children and adults alike were well-acquainted with his work, particularly his epic poems on historical subjects: “Paul Revere’s Ride,” “Hiawatha,” “Evangeline,” and others. Longfellow lived most of his adult life at 105 Brattle Street, which today is home to a national historic site commemorating his life and work (which was the site of this tour’s first stop, featuring Phillis Wheatley).

Longfellow’s poem “The Village Blacksmith” became instantly popular upon its 1840 publication. The blacksmith Dexter Pratt, who lived and worked at the nearby house at 54 Brattle Street, served as Longfellow’s inspiration. The poem extols Pratt as an ideal nineteenth-century citizen and a model for all men to emulate. He is hardworking, strong and honest, a faithful Christian who mourns the death of his wife and is devoted to his children.

The first line of the poem, “Under a spreading chestnut-tree,” refers to a magnificent tree that stood at this spot until 1876. When the tree was cut down due to safety concerns, children of Cambridge raised money to have a chair constructed from its wood and presented it to Longfellow on his 72nd birthday. Today, this plaque commemorates the site where the tree once stood, as well as the poet it inspired.

“Under a spreading chestnut-tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.”

Read the entire poem at the Maine Historical Society’s website.

Stop 4: Pauline Hopkins: Of One Blood (1903): 132 Mount Auburn Street

After years of relative obscurity, Pauline Hopkins is hailed today as one of the most influential African-American writers of the early twentieth century, a pioneer in both her literary work and her social thought. Born into an artistic family in Portland, Maine in 1859, Hopkins grew up in Boston, relocated to Cambridge in the 1890s, and lived there until her death in 1930. She began her career as a musician, performing throughout New England as a soprano and also composing musical plays (most of which, unfortunately, have been lost). Hopkins later became editor-in-chief of Colored American Magazine, a prominent periodical in which she once published an admiring biographical profile of Phillis Wheatley. Upon turning her attention to literature, she published several short stories and three major novels.

Hopkins spent much of her adult life in Cambridge, living in both North Cambridge and Cambridgeport, and featured the city prominently in her literary works. Her proto-science-fiction novel Of One Blood, published in 1903, has deep connections to a variety of locations around the city. Reuel Briggs is the protagonist of the novel, a destitute but brilliant medical student who hides his mixed-race origins and lives in a “third-rate lodging house near Harvard Square.” His close friend, Charlie Vance, resides luxuriously on Mount Auburn Street in a “spacious house with rambling ells, tortuous chimney-stacks, and corners, eaves and ledges; the grounds were extensive and well kept telling silently of the opulence of its owner.”

It is at the haunted house next door to the Vance estate that the spectacular plot begins to unfold: Reuel Briggs, the medical student, falls in love with Dianthe Lusk, a beautiful Fisk Jubilee Singer, after he revives her from a “dual mesmeric trance.” But Reuel’s friend Aubrey, secretly in love with Dianthe, convinces Reuel to travel to Ethiopia with an archaeological expedition, during which Reuel discovers a hidden ancient African society, Telassar. Meanwhile, Aubrey persuades Dianthe to abandon Reuel and marry him instead. A telepathic connection with Dianthe enables Reuel to discover what Aubrey has done, but when Reuel returns to Cambridge, it is revealed that these three characters – unbeknownst to any of them – are actually siblings, “of one blood.” Traumatized, Aubrey poisons Dianthe and then commits suicide. Only Reuel, who is crowned king of Telassar, finds happiness.

While Hopkins does not give a precise address for the Vance estate on Mount Auburn Street, this particular location was chosen because it evokes the leafy, luxurious ambience that Hopkins describes.

“The Vance estate was a spacious house with rambling ells, tortuous chimney-stacks, and corners, eaves and ledges; the grounds were extensive and well kept telling silently of the opulence of its owner. Its windows sent forth a cheering light…

“[The house next door] has been known for years as a haunted house, and avoided as such by the superstitious. It is low-roofed, rambling, and almost entirely concealed by hemlocks, having an air of desolation and decay in keeping with its ill-repute.”

Stop 5: William Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury (1929): Plaque, Larz Anderson Bridge

William Faulkner’s personal ties to Cambridge are less extensive than those of other writers on this tour, but his literary connections to the city are profound. The place most deeply associated with Faulkner is, of course, the American South. A Mississippi native, he spent much of his life in the small town of Oxford, and set the majority of his works in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County in the state. After dropping out of high school, joining the Canadian Royal Air Force, and working as a clerk and postmaster, Faulkner began to focus on writing. His first novel was published in 1924, and his second, The Sound and the Fury, in 1929.

The Sound and the Fury tells the story of the decline of an aristocratic Mississippi family, the Compsons. The novel’s four sections do not follow a traditional linear path, but rather each offer a detailed account of events, each narrated by a distinct voice. The second of these sections is about the oldest Compson brother, Quentin. A freshman at Harvard in 1910, he is emotionally distraught over his sister Caddy’s pregnancy in particular, and over the decline of his family and cultural heritage more broadly. June 2, 1910 begins as an ordinary day for Quentin, but quickly transforms into a series of progressively more troubling events. His tormented memories merge imperceptibly with strange personal encounters as he travels throughout Cambridge and Watertown. By the end of the day, Quentin has purchased a set of tailor’s weights, attached them to his ankles, and jumped off the Anderson Bridge, drowning himself in the Charles River.

Walk along the eastern side of the Anderson Bridge, to about the middle of its span, and you will see a small, bronze plaque that commemorates this fictional character. “Quentin Compson,” it reads. “Drowned in the odour of honeysuckle. 1891-1910.” Placed anonymously on the bridge during the 1960s, the plaque demonstrates that not only has Cambridge inspired literary creations, but literary creations have inspired the city’s landscape as well.

“I began to feel the water before I came to the bridge. The bridge was of gray stone, lichened, dappled with slow moisture where the fungus crept. Beneath it the water was clear and still in the shadow, whispering and clucking about the stone in fading swirls of spinning sky.”

A great interactive site for learning more about The Sound and the Fury can be found here.

Stop 6: Jorge Luis Borges: “The Other” (1972): Bench by the Charles River

“It was in Cambridge, back in February, 1969, that the event took place.” The simplicity of this sentence belies the mysterious complexity of the story it introduces, Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Other.” Its narrator proceeds to describe a strange encounter: as he relaxes alone on a bench by the Charles River on a chilly winter morning, he suddenly senses the presence of a visitor. The interloper is none other than himself, or, more precisely, his past self. The two embark upon a bizarre sort of family reunion, each trying to discern whether their implausible meeting truly is occurring.

From the first moments of the story, the riverside setting enhances its mysterious ambience. It is morning, around ten o’clock, and the half-frozen gray river is strewn with ice. The movement of the river, in fact, is what first makes Borges think about the passage of time – one of the story’s central themes. When the younger Borges sits down, he is convinced that this is another river entirely, and that they are sitting in a bench in Geneva. Recounting a series of historical events from the past fifty years, the older Borges tries to convince his visitor that time has passed and it is, in fact, 1969. The younger Borges insists that he must be dreaming. At the end of the story, the older Borges (the narrator) decides to dispose of a coin given to him by his younger self by throwing it into the “silver river.” Time continues to march on, whether or not this mysterious meeting of two versions of oneself actually occurred; so does the river that inspired Borges to come sit here in the first place, prompting the fateful meeting.

“The Other” draws inspiration from Borges’s own experiences. Born in Buenos Aires in 1899 to a Uruguayan mother and Argentinean-English father, he later studied in Switzerland and traveled throughout Europe. Interestingly, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was one of the first English-language writers he read (and he also, later in life, was a frequent translator of William Faulkner’s work). He began writing as a child, published his first work at age nine, and as a young adult was well-known throughout South America.

Borges gained renown in the English-speaking world beginning in 1961, when he was awarded the prestigious Prix International. He came to Cambridge in 1967 to give the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard and teach courses there. Like the narrator of the story, he would often repose by the Charles while in Cambridge.

His time in Cambridge marked a late turning point for Borges. Just 12 years earlier, in 1955, his vision had deteriorated, leaving him entirely blind: a difficult scenario for anyone, but especially so for one whose entire life was dedicated to the written word (in addition to being a writer and lecturer, he was also director of the National Library in Buenos Aires). By 1967, he was hardly writing at all. This changed when he met the translator Norman Thomas di Giovanni at Harvard. The friendship they developed encouraged Borges to begin writing again, and this story, “The Other,” is one product of this newfound encouragement.

In another essay, Borges once wrote, “Time is a river that carries me away, but I am the river.” Perhaps his moments by the Charles formed part of the inspiration for this way of thinking.

“It was about ten o’clock in the morning. I sat on a bench facing the Charles River. Some five hundred yards distant, on my right, rose a tall building whose name I never knew. Ice floes were borne along on the gray water. Inevitably, the river made me think about time.”

Stop 7: Junot Diaz: “The Cheater’s Guide to Love” (2012): Running Path by the Charles River

Junot Diaz is an MIT professor, and his clear familiarity with the city is evident throughout his work. In his most recent book, the 2012 short story collection This Is How You Lose Her, Diaz sets the book’s final and most complex story, “The Cheater’s Guide to Love,” in Cambridge. The story’s protagonist is Yunior, a patently semi-autobiographical character. Like Diaz, Yunior is a Dominican immigrant who grew up in New Jersey and now teaches writing at a Boston-area university. Indeed, in one interview, Diaz referred to Yunior as “a distorted extreme version of me.”

The story begins with a traumatic breakup as Yunior’s fiancée leaves him upon discovering that he has cheated on her with fifty different women. In an effort to turn his life around, Yunior takes up running along the river, “in the morning and…late at night, when there’s no one on the paths next to the Charles.” It seems promising, but doesn’t quite work. After Yunior gets injured, he finds himself back in his original predicament.

Diaz has spoken about his ambivalence toward Boston and Cambridge, which never feel quite like home to him. Yunior’s contentious relationship to the city reveals an opinion of Cambridge less positive or inspirational than that of most writers featured on this tour. Unabashedly critical of his surroundings, Yunior struggles to find emotional security in a tumultuous city. His dissatisfaction with his current physical surroundings adds a layer of depth to the story’s portrayal of his emotional state.

“It’s your new addiction. You run in the morning and you run late at night when there’s no one on the paths next to the Charles. You run so hard that your heart feels like it’s going to seize.”

Stop 8: Jhumpa Lahiri: The Namesake (2003): Café Pamplona, 12 Bow Street

The contemporary Indian-American author Jhumpa Lahiri has both personal and literary ties to Cambridge: her family moved to Cambridge when she was two years old, though they relocated shortly afterwards to Rhode Island. Yet Cambridge resonates throughout her work, and many of her short stories, as well as her 2003 novel The Namesake, powerfully evoke various locations around the city.

The Namesake begins with the birth of the main character, Gogol Ganguli, at Mount Auburn Hospital. He grows up in Central Square and spends his childhood in Cambridge. As Gogol comes of age, his experiences as the child of immigrants instill in him a sense of questioning, even conflict. His indecision over which name he should be known by – which is, as the title suggests, a recurrent question throughout the book — reverberates and expands into a series of broader challenges: how to reconcile his multiple identities? How to fulfill his obligations to his parents while also exploring the life he desires? How to come to terms with his own and his family’s past?

Lahiri has spoken in interviews about her own experience with such tensions, and the close parallels between her experiences and Gogol’s are clear. She once stated, for instance: “For me, it was always a question of allegiance, of choice. I wanted to please my parents and meet their expectations. I also wanted to meet the expectations of my American peers, and the expectations I placed on myself to fit into American society. It’s a classic case of divided identity, but depending on the degree to which the immigrants in question are willing to assimilate, the conflict is more or less pronounced.”

While a college student, Gogol returns to Cambridge with a girlfriend and visits Café Pamplona. The day they spend together in Cambridge draws these difficult questions to the forefront of Gogol’s thoughts.

“They have lunch at Café Pamplona, eating pressed ham sandwiches and garlic soup off in a corner.” The beloved institution closed in 2020.

Stop 9: Andre Aciman: Harvard Square (2013): Café Algiers, 40 Brattle Street

Centuries after Phillis Wheatley sent her poem to George Washington on Brattle Street, contemporary writers continue to seek inspiration from the city of Cambridge. Andre Aciman’s new novel Harvard Square, published in April 2013, has already become an enormously popular testament to life in Cambridge. Like the works featured on this tour by William Dean Howells, Jorge Luis Borges, Junot Diaz, and Jhumpa Lahiri, it draws upon Aciman’s personal experience (he was a Harvard graduate student in the 1970s).

Harvard Square centers around a friendship that begins in Café Algiers on a hot summer evening in 1977. The narrator, an Egyptian graduate student, meets a Tunisian cab driver over coffee, and the two embark on a close, yet complicated, friendship. Both are deeply disillusioned: the narrator with the rigid stuffiness of the academic world he is attempting to access, and the cab driver, Kalaj, with what he calls the “jumbo-ersatz” nature of superficial American culture. As the summer progresses and their friendship intensifies – then sours – Cafe Algiers remains central to their shared experience.

Aciman’s beautiful descriptions of the cafe highlight the sense of stability it provides to characters far from home. In the narrator’s words, “We called Café Algiers Chez Nous, because it was so obviously made for the likes of us – part North African, part faux-French, part dreamplace for the displaced, and always part-something-from-somewhere-else for those who were neither quite here nor altogether elsewhere.” After their chance meeting there catalyzes an unforgettably significant summer,Cafe Algiers anchors the narrator and Kalaj to each other and to the multifaceted Cambridge world they inhabit.

“One could spend an entire day at Café Algiers. It was a tiny, cluttered, semi-underground café off Harvard Square that held no more than a dozen tiny, wobbly tables and that looked like a miniature Kasbah about to spill onto the floor.”

Read “Monsieur Kalashnikov,” a 2007 short story by Aciman which helped inspire Harvard Square, at The Paris Review.

This tour was made possible through funding by the Cambridge Heritage Trust.