Self-Guided Tour: Central Square Activism From the 1960s to Now

By Amelia Zurcher, Society Intern, July 2019

This tour was made possible by the Cambridge Heritage Trust

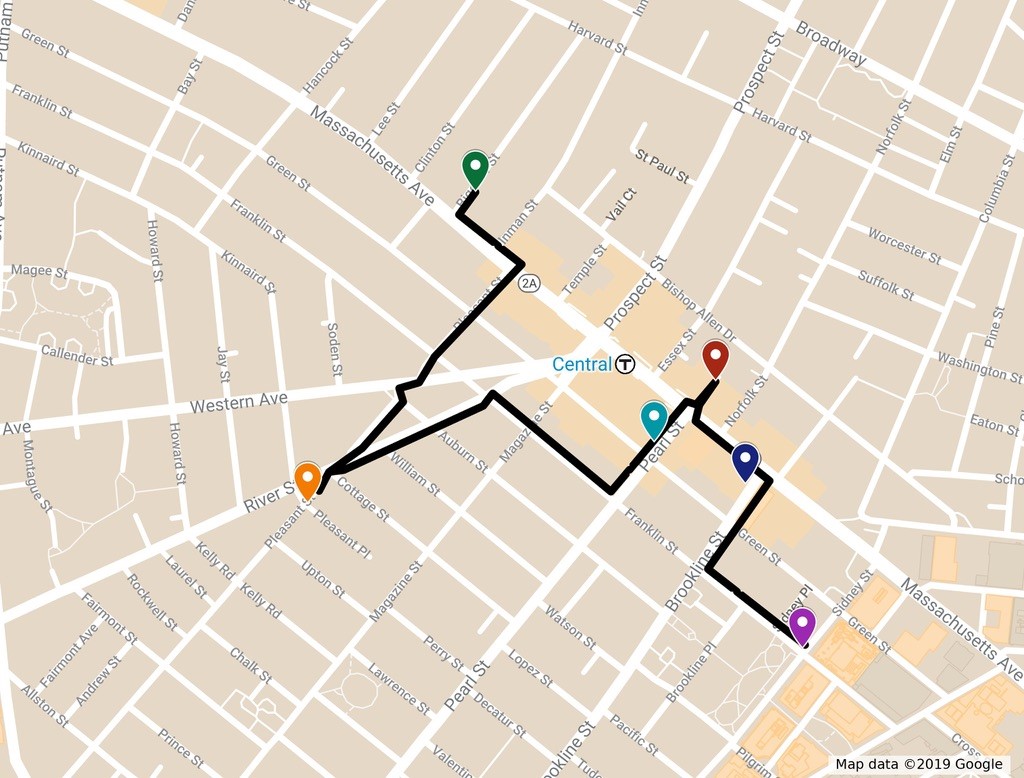

Tour Route

Overview and History

Central Square has been characterized for much of its history as a working-class neighborhood. In the 1960s, the demographics around Central Square began to change subtly. The growth of local universities led to greater numbers of students in search of housing in the neighborhoods between M.I.T. and Harvard University. At the same time, as blue-collar jobs declined, working-class families began to leave Central Square. With many students involved in the developing social movements of the mid-to-late 1960s, the changing communities surrounding Central Square merged the goals and visions of these movements with other more local matters. During the sixties, local residents of Cambridge were also organizing around the planned construction of the interstate highway system through the city. In the following decade, housing concerns amidst a housing crisis and university expansion also led to a push for tenants’ rights and increased community services.

Although each cause traced its origins to specific moments and contexts, the activities and ideals of these movements continued into later decades through increased concern with women’s liberation, housing, and civil rights. The causes promulgated by activists over the last sixty years in and around Central Square demonstrate an active pursuit by Cambridge residents for continual change.

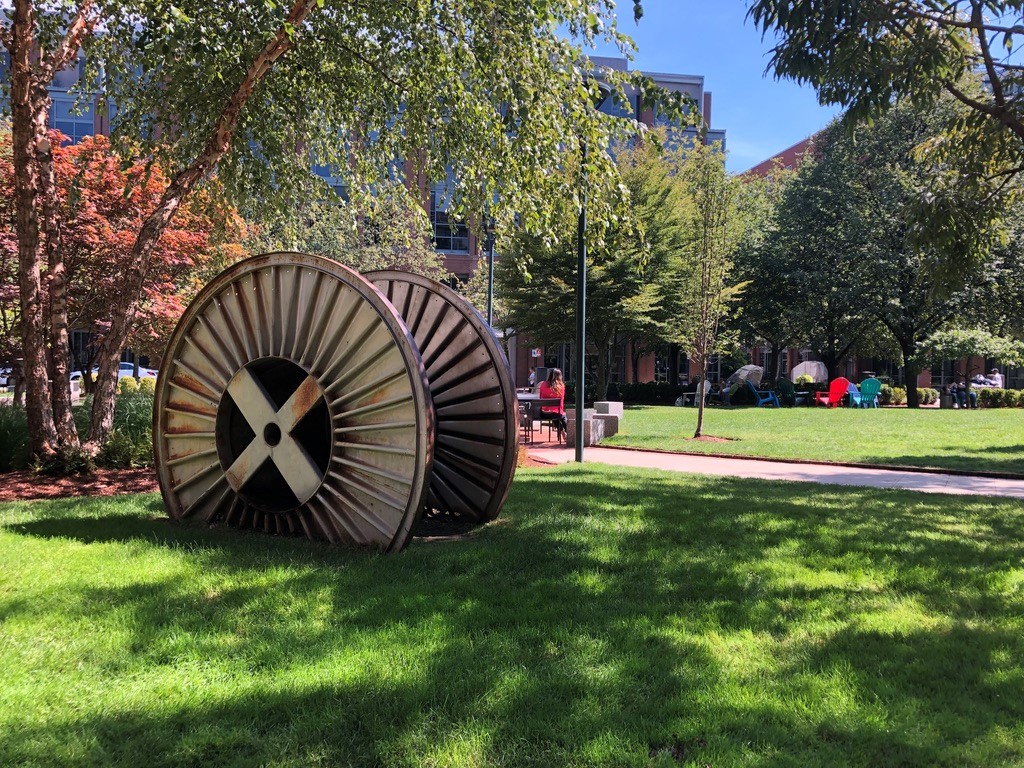

Stop 1: Site of former Simplex Wire and Cable Company

Corner of Sidney Street and Franklin Street

As the mid-twentieth century saw many industries and businesses close, new development plans for the Central Square area sparked activism around housing. After the closing of the Simplex Wire and Cable Company in the 1960s–and the subsequent purchase of the large site in 1969 by MIT– many feared for the future of the remaining homes on these streets and the surrounding communities. As rents and taxes increased in Cambridgeport, blue-collar jobs, such as those provided by the Simplex Wire and Cable Company, were disappearing.

In response, the community-based Simplex Steering Committee formed in 1974. It sought to promote neighborhood priorities as MIT developed plans for the site. The group demanded that future use of the site prioritize low- and moderate-income housing, open spaces, shopping, transportation, and light industry expansion. The priorities were identified in a neighborhood referendum that was approved by nearly 800 local residents of Cambridgeport. As part of their grassroots efforts, the Simplex Steering Committee planned demonstrations that included picketing at MIT’s graduation. They also created a tenants’ union phone chain to protect tenants by organizing gatherings at the sites of attempted evictions.

Further organizing occurred after many tenants were forced out of their homes on nearby Blanche Street in 1979. Many of these buildings remained vacant, causing controversy for years. A series of protests and rallies started in 1987 when MIT released re-zoning plans that did not address the priorities that nearby communities had identified years earlier. This included the creation of a Tent City on an MIT-owned vacant lot on Blanche Street. Eventually, this activism led to the construction of hundreds of residential units, especially reserved for low-income families, although the number created fell short of original neighborhood demands.[1]

Stop 2: Crosswinds Mural

Corner of Mass Ave and Brookline Street

At the top of Brookline Street is a mural by Daniel Galvez called Crosswinds. Painted in 1992, it is a companion piece to a 1986 mural by Galvez called Crossroads located on the Green Street Parking Garage, roughly one block away. Crossroads, which has since mostly disappeared, presented a collage based on the photographs and memories of local residents, such as an Indian restaurant waiter and a shoemaker. Crosswinds, painted five years later, also centers people with a focus on the multi-cultural character of the area. The artist stated his intent was to capture the “diversity and vibrancy of people” and the “wonderful multi-cultural spirit” of Central Square through the faces of real people photographed by local resident Jeff Dun. Several of the public art pieces in this area similarly follow the message of community togetherness and reflect the contributions and ideas of local volunteers.

Stop 3: Potluck Mural

Parking Lot behind 565-567 Mass Ave

The next stop lies at the other end of Graffiti Alley, where artists color Central Square with creative designs. The art found in Graffiti Alley is never given time to fade; artists change its walls each day, reflecting artistic expression in a given moment. Contrastingly, community murals painted on the buildings of Central Square, like Crossroads, change over time. Those that remain reflect a local dedication to preserving artistic messages considered valuable to the neighborhood.

One longstanding example, The Potluck, is a community mural created in 1994. The 2,000 square foot mural was designed, painted, and imagined by David Fichter and over 60 others, including many local community members. The mural illustrates a potluck scene with residents from Area 4 and is meant to display a multi-ethnic image of the community. In one oral history, Fichter explained that community members of Area 4 who stopped by as he was painting the mural represent many of the faces depicted here.

Community arts have also appeared in Central Square through the support of local organizations such as the Community Art Center and Central Square Theater, both of which especially demonstrate the important involvement of youth in activist and community art.

Stop 4: Activist Businesses of the 1960s and 1970s

15 Pearl Street

Along Mass Ave in the 1960s and 1970s, many storefronts and office spaces were occupied by anti-war organizations, second-wave feminist publications, and co-operative businesses. Co-ops had become popular as part of the mid-twentieth century counterculture. The Cambridge Food Co-Op opened in the early seventies at 581 Mass Ave. Residents could become members of the food co-operative by working at the store. In the 1970s one could find other co-operative businesses near Central Square, such as the 100 Flowers Bookstore and New Community Projects at 15 Pearl Street. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, New Community Projects provided information to people within the Central Square area about existing co-ops, as well as guidance about starting alternative ventures like collectively-owned homes and businesses.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, meeting places for activists abounded in Central Square. At Sgt. Brown’s Memorial Necktie Coffee House on Pleasant Street, people active in draft resistance and the anti-war movement gathered. The coffee house’s name came from the stolen tie of a military officer that hung in a frame on the wall.

Radical or counterculture newspapers created and distributed near Central Square demonstrate how such publications have historically played a role in activism. At 2 Brookline Street, activists published the Old Mole, a newspaper that addressed issues ranging from opposition to the war in Vietnam to civil rights. Others included Sojourner (143 Albany Street), Sister Courage (897 Main Street), Hysteria (2 Brookline Street), and El Mundo (20 Columbia Street). A group called Female Liberation created a particularly popular publication called Second Wave: A Magazine of the New Feminism. It focused primarily on issues of ideological conflict and debate within the feminist movement. Between 1968 and 1974, the organization worked out of 552 and, later, 639 Mass Ave. Although the organization dissolved and left Mass Ave in 1974, the publication outlived the space and group itself, and remained in print until 1983.[2]

Stop 5: The Women’s Center

46 Pleasant Street

Before moving to 46 Pleasant Street, the Cambridge Women’s Center had operated out of an under-utilized Harvard building at 888 Memorial Drive in Riverside. The center was created in 1971 on International Women’s Day when a group of activists marched from Boston to Cambridge to demand a women’s center. For ten days, feminist groups, including Bread and Roses, occupied the site. In January 1972, the center moved to its current location at 46 Pleasant Street, using funds donated during the occupation for a down payment. The creation of the Women’s Center followed a national movement calling for the development of women-only spaces, and the creation of the Women’s Center in Cambridge further inspired others across the country.

When first setting up the center, its founders met at an office in 595 Mass Ave. They looked to similar examples, like Female Liberation, to decide how their organization would be different. From its earliest years, the Cambridge Women’s Center (sometimes called the Women’s Educational Center) stressed the need for teaching new skills to women, such as karate, auto mechanics, and carpentry. The center established a Women’s School in 1971, which met at 595 Mass Ave. A class on health led to the creation of a Community Women’s Health Center that operated in Central Square from 1974 to 1980.

Although the school closed in 1992, the Women’s Center continues to operate near Central Square. Other organizations that serve Cambridge women also trace their origins back to this site, with the Transition House and Boston Area Rape Crisis Center both founded as a result of meetings held here in 1972 and 1976, respectively.

Stop 6: Cambridge City Hall

795 Mass Ave

Cambridge City Hall has been a site for political engagement, debate, and community building since it was built in 1889 and the 1960s and 1970s were no exception. The focal point of numerous anti-war protests in the 1960s, in the 1970s Cambridge City Hall was also the site of demonstrations demanding diversity in local representation. At a time when there were very few black employees working for the city, a demonstration was organized to demand that more jobs be filled by black residents of Cambridge. Decades later, Lorraine Scott recalled the march in an oral history: “Traffic was stopped. We filled the sidewalk and covered the steps of City Hall, the YMCA, and the Post Office. A small group of us met in the mayor’s office.”[3]

During the 1970s, debates surrounding rent control and police brutality also took place in this space. The issue of rent control followed a growing housing crisis in Cambridge exacerbated by expansion by Harvard University and MIT. More protests arose after Larry Largey, a local teenager, died in police custody. Both of these moments were captured in Olive Pierce’s photographs of Cambridge City Council meetings in the early 1970s. These photographs show crowds at City Hall sitting on the floor, packing a balcony, and standing outside the building entrance.

Several decades later, City Hall again became a gathering site for change in Cambridge when, in 2004, the building was the site of the country’s first same-sex wedding ceremony. Although a celebratory moment, it followed years of political activism around the need for marriage equality. On May 17, 2004, Massachusetts ordered that town clerks begin issuing marriage licenses. At 12:01 AM City Hall opened its doors to many people who eagerly applied. Nearly 5,000 Cambridge residents gathered to cheer on those emerging from City Hall.

Political activism by the Cambridge Lavender Alliance helped to lay the groundwork for this moment. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s the organization provided information, services, and a sense of community for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in Cambridge. The Pride Brunch at City Hall, first organized by the alliance, has become an annual tradition continued by Cambridge’s current LGBTQ+ Commission.

Central Square: A Unique History of Activism

Community engagement has appeared in a variety of forms near Central Square, such as publications, radical businesses, public art, protests, politics, and social services. Other parts of the city have also historically been sites of engagement, but Central Square is an especially interesting site of activism.

One reason is its proximity to several universities. The local universities impact the use and development of the area as well as the demographics of its surrounding communities. Because of this, Cambridge residents have continually organized in Central Square through or against local universities.

Another reason is Central Square’s location at the center of Cambridgeport, Riverside, the Port, and Mid-Cambridge. While Central Square can be seen as peripheral to each of these neighborhoods, it also lives up to its name as a center for people in Cambridge. This characteristic of Central Square has encouraged involvement over decades within communities about neighborhood concerns.

Its location near City Hall and other local government structures also makes Central Square especially relevant to activists and other residents of Cambridge. Cambridge residents have civically and socially engaged by working within or protesting against city government.

Each of these factors, among others, has come together throughout Central Square’s recent history to create a unique setting of activism. Central Square and its surrounding neighborhoods have been sites of tremendous social and political activity. Here, activists sought to achieve visions of affordable housing and food, equal representation, and civil rights. As settings of debate, protest, community building, and organizing, both past and ongoing, Central Square has historically sparked such community efforts.

Sources and Further Reading:

Sarah Boyer, Crossroads: Stories of Central Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1912-2000 (Cambridge Historical Commission, 2001).

- The oral histories within Crossroads collected by Sarah Boyer is essential reading for understanding the diverse and ever-changing experiences of people within Central Square over the years. Its many stories depict the transformations of everyday life, businesses and industries, and activist activity over time.

Papers of Wini Breines, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

- As a member of Bread and Roses, a Cambridge-based women’s liberation organization, and a sociologist who has written about mid-twentieth century activism, her papers include a great deal of information about the Second-Wave Feminist movement in Cambridge and more broadly.

Cambridge Commission on the Status of Women, Mapping Feminist Cambridge: Inman Square, 1970s-1990s, July, 2019.

- This walking tour and other tours by the Cambridge Women’s Commission in Area IV, Mid-Cambridge, Cambridgeport, and Riverside/Cambridgeport highlight the extensive and complex histories of women and feminist organizing in Cambridge.

“Cambridge Public Art”, Cambridge Arts Council, 2002, www2.cambridgema.gov/cac_5_4_2009/public_art_tour/map_08.pdf.

Cambridge Public Art Fact Sheet, Cambridge Arts Council, 2019, www.cambridgema.gov/arts/publicart/percentforart/publicarttour.

- The Public Art Map, and its accompanying fact sheets, document the public art in neighborhoods such as Central Square that has been sponsored by the city. Similarly, the Cambridge Public Art Tour made available by the Cambridge Arts Council contains descriptions of public and community art throughout the city.

Cambridge Lavender Alliance Collection, The History Project: Documenting LGBTQ History, Boston, Mass.

- Among materials in the archives of the History Project dedicated to documenting LGBTQ history in the Boston area and New England is a collection about the Cambridge Lavender Alliance, which had been donated by one of its members Marcia Deihl. The tour especially made use of the subject files for Cambridge Lavender Alliance at The History Project (including many newsletters and flyers created by the organization).

Cambridge Women’s Heritage Project, June 2017, Cambridge Women’s Commission and Cambridge Historical Commission, https://www2.cambridgema.gov/historic/cwhp/index.htm.

- The Cambridge Women’s Heritage Project, which is jointly sponsored by the Cambridge Women’s Commission and the Cambridge Historical Commission, aims to document the contributions of women and women’s organizations in Cambridge throughout the city’s history.

Bill Cavellini Papers, Series II. Simplex Steering Committee, 1945-2002, Cambridge Historical Society, Cambridge, Mass.

- The Bill Cavellini Papers at Cambridge Historical Society include many documents related to the organizing around the former Simplex Steering Committee, especially between the 1970s and 1980s. Particularly relevant materials are photographs of rallies, newspaper clippings about Tent City, and leaflets and notes about the zoning plans and neighborhood planning meetings.

Bill Cunningham, “One Hundred Years of Activism – Or Was It?” Cambridge in the Twentieth Century, Edited by Daphne Abeel (Cambridge Historical Society, 2007).

- This chapter in Cambridge of the Twentieth Century provides a broad overview of the long history of activism and community engagement in Cambridge.

Tim Devin, Mapping Out Utopia: 1970s Boston-Area Counterculture, Vol. 1 (Free the Future Press, 2017).

- Mapping Out Utopia is an essential tool for identifying spaces that were once part of 1970s counterculture in Cambridge. The book maps out sites of collective, feminist, and other activist organizations.

Female Liberation, A Radical Feminist Organization Records, Northeastern University, Archives and Special Collections, https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/896.

- Records about Female Liberation, the activist group dedicated to women’s issues in the Boston area who also published the magazine Second Wave, can be found in the Archives and Special Collections at Northeastern University. These materials are available along with others related to the Women’s Center’s Women’s School and local newspapers Sojourner and Old Mole.

Women’s History Tour of Cambridge, “Feminist Footsteps Around Cambridge, Tour 1”, Goddard College.

- This walking tour published by Goddard College includes locations near Central Square linked to the publications of newspapers Sojourner, El Mundo, Hysteria, Sister Courage, and Second Wave.

Katie MacDonald, “Same Sex Marriages Cambridge City Hall 795 Massachusetts Avenue”, Innovation in Cambridge, (Cambridge Historical Society, 2012), www.historycambridge.org/innovation/Same%20Sex%20Marriage.html.

- This essay about the history of same-sex marriage at Cambridge City Hall is part of a collection of writings about innovations in Cambridge, written by Katie MacDonald in a project with the Cambridge Historical Society.

Olive Pierce Collection, The Cambridge Room, Cambridge Public Library Archives.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/cambridgeroom/albums/72157702506022672. The photographs by documentary photographer Olive Pierce at The Cambridge Room highlight tremendous levels of concern and activist activities relating to police brutality and rent control in the early 1970s. Many of these photographs, among others by Olive Pierce, are digitized and available online.

Anne Raver, “DA investigation begins ‘Witness’ describes towers arrest”, Cambridge Chronicle, 26 October 1972.

- This article from the Cambridge Chronicle in October of 1972 discusses the arrest and tragic death of Larry Largey, as told by a witness at the site.

Mark Vassar, “From the Archives: The Simplex Steering Committee”, The Cambridge Historian: The Newsletter of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume XVI, No. 1, Spring 2016, https://historycambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CHS-Spring-2016-Newsletter.pdf.

- The article provides key background information about the Simplex Steering Committee. It introduces the Bill Cavellini Papers at Cambridge Historical Society as a resource for the history of late twentieth-century housing activism in Cambridge.

Paper of Betsy Warrior, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

- Comprised of the documents of a local feminist activist, the Betsy Warrior Papers include organizational records related to the Women’s Educational Center (as the Women’s Center was formerly known) and of Transition House, a women’s shelter that began in meetings at the Women’s Center. The collection also is home to many photographs documenting the 1971 takeover of the underutilized Harvard University building at 888 Memorial Drive.

[1] You can explore the history of the Simplex Steering Committee and other efforts surrounding housing and tenants’ rights further in the Bill Cavellini Papers at the Cambridge Historical Society or on the website: https://historycambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CHS-Spring-2016-Newsletter.pdf.

[2] Records related to Sister Courage, Sojourner, and Second Wave can be accessed in the archives and special collections of Northeastern University. You can also read further about the Old Mole on the Cambridge Historical Society’s website: Dick Cluster, “Swimming in the Countercultural Sea”, Cambridge Historical Society, https://historycambridge.org/research/swimming-in-a-countercultural-sea-by-dick-cluster/.

[3] Sarah Boyer, Crossroads: Stories of Central Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1912-2000 (Cambridge Historical Commission, 2001), page 192.