Elias Howe, Jr., Inventor Of The Sewing Machine (Part 1)

Elias Howe, Jr., Inventor Of The Sewing Machine

1819-1919 A Centennial Address

Born In A Cradle Of Invention

The succession of master minds in a particular locality compels us to believe in the spiritual consanguinity of genius. It is an heredity much greater than that of blood. It is an heredity of spirit, that second birth that is not flesh-born but spirit-born. Especially do we need the transmission of its influence in America and in New England today. With such a reflex action upon us today of geniuses of yesterday, America celebrates the centennials of founders, authors and creators; and with this motive, we celebrate the birth of the inventor of the sewing machine, Elias Howe, Jr., born in the hills of Spencer at the Commonwealth’s heart, July 9, 1819, one hundred years ago. Though born but 27 years before, Howe patented, September 10, 1846, 73 years ago, the completed creation of his genius, a mechanism that revolutionized industry — the sewing machine, invented in Cambridge.

The New York Independent said not long ago that within the last 100 years no ten names could be assembled in one zone, greater than those of the ten master minds who sprang within a radius of ten miles of Worcester. Close upon us, in addition to that of Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross, are the centenaries of two of these great internationally famous creators, born a century ago, and within a few miles of one another. Within a month of the centenary of Elias Howe, occurred the centenary of William T. G. Morton of Charlton, discoverer of ether. Morton was also born on a Worcester County farm in 1819, the same year as Howe, and in the same year, 1846, he patented his famous discovery. In the same years of like starvation and poverty from 1843 to 1846 that Howe worked up the steps to his invention, Morton worked up to his masterpiece of anaesthesia. These two Worcester County boy neighbors, thus each 27 at the climax of their creations, were each under twenty-five when their great ideas captured their vision at the same time.

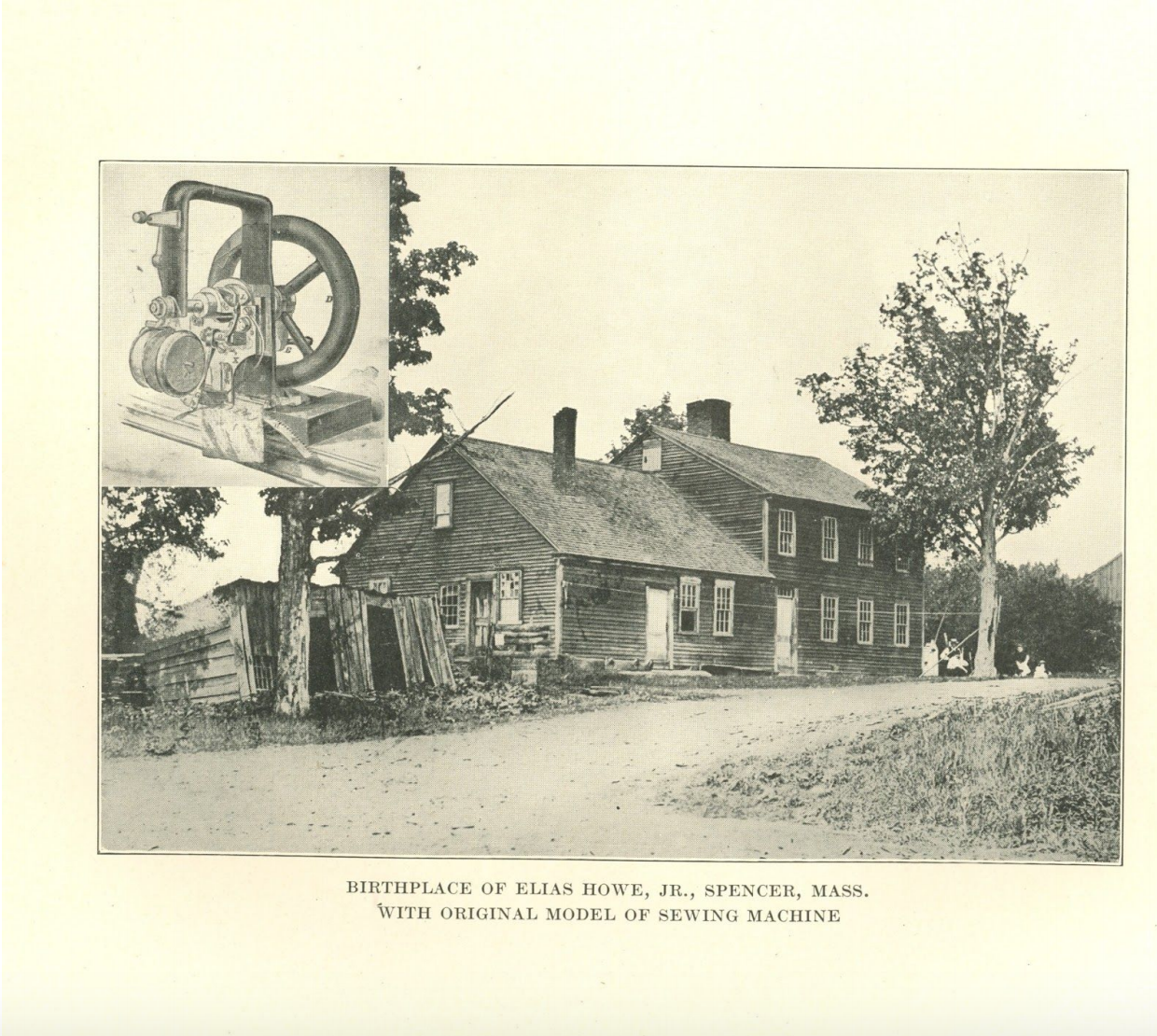

There are external ways of immortalizing that appeal to the eyegate of every passer-by — to every lad driving the cows home, and to every flashing auto. One is in “marked” birthplaces. The Howe Memorial Association has marked the birthplace of the Howe inventors — two miles out of Spencer, 15 feet back of two threshold stones that stand semi-exedra style, with doorstep base and slanting pillar indented in perpetuo with bronze plate. Here are the very steps trodden by the feet of the barefoot Howe boys. There were eight children in the family. Today the mill pond sings through the sluices across the road and rumbles through the broken iron gauges of the old mills. Three of these whirred their flanges there. Beside the old house, a perfect stone raceway allows the water to escape in a tempting, rippling trout brook that gurgles from back in the forest.

Already inventive streams had been strong in the family blood, blending three-fourths Bemis and one-fourth Howe. Captain Edward Bemis in 1745 commanded a Massachusetts company. When the French in retreat spiked their guns, on the inspiration of the moment he invented a way to drop out the spikes by heating and expanding the metal through building fires under them. In the home settlement, by the little dams and waterfalls challenging Yankee invention, machines for shoe pegs and other devices were long since made by the other members of the family. By the time the older Howe family in the late seventeen hundreds walked over those stone steps that now make the “markers,” they were manufacturing grist and sawn lumber in three crude mills opposite the house. Here were made all of the simple essentials for bringing up a Puritan Yankee family — grist for bread, and lumber for shelter, and shingles, and cider, perhaps over one-half of one per cent, a proportion not unknown to the earliest Puritans.

In the smaller wing of the old house, dating from the seventeen hundreds, were born Elias Howe, Jr.’s father’s two brothers, William, the fifth son, and Tyler, the fourth son. William was the inventor of the truss bridge. Unlike Elias, his nephew, it was later in life that William Howe had caught this fever for invention. He was then an inn keeper of a tavern standing till 1871, being a carpenter and builder also. In October, 1919, in an original letter from Richard Hawkins, a family connection at Springfield, came to me this authoritative sketch of him:

William Howe, who invented the celebrated Howe Truss Bridge in 1838 or 1839, was born in Spencer, Mass., May 12, 1803. He was a carpenter and builder and while erecting a church in Warren, Mass., which required a roof of some length, he conceived and built it under the system which has since been known as the Howe Truss. He afterwards built a bridge by the same system, about 60 feet long, in West Warren. At that time the Western Railroad was extended westerly from Springfield across the Connecticut River, a series of 7 spans of about 180 ft. each, single track.

He patented the bridge system in 1840 and it was once renewed. From that time to his death he had no other business but to sell rights to the patent. He received a large amount of money for its use by railroads and private parties, who bought all the state rights. As they were mostly his relatives, the business became a family affair.

The system was based on a combination of vertical rods of iron and vertical wood braces with top and bottom chords of timber. The plan was so easily figured for strain loads, and so safe and correct in principle, that the bridge became almost universal for railroads and towns, and was largely used in foreign countries. Major-Gen. Whistler, who built the Western Railroad and afterwards built the railroad from Moscow to St. Petersburg, used the Howe Bridge in its construction. The Long Bridge, so-called (later taken down) at Washington, was of the same design.

There have never been any changes made in the original design except that the angle block formerly made of wood was changed to iron by Mr. Howe.

The bridge or truss system continues to be used in roof trusses and small spans, but the modern loads are so much increased that it has become impracticable to use the combination of the wood and iron, and iron bridges have become necessary for work of any magnitude.

Mr. Howe’s residence after his invention was in Springfield, Mass. Tyler Howe, his brother (1800-1880), who had gone in a Pacific Ocean boat upon a disappointed quest for gold in California, hit upon the idea of a spring bed to take the place of the rigid berths in which he had been tossed about while on the vessel. He showed it to A. G. Pear of Cambridge in San Francisco in 1853. Then in 1855 he patented the elliptical spring bed and opened a successful factory in Cambridge. His house is still standing back of those old mill sites of his father near Spencer.

In 1819 Elias Howe, Jr., was born in the larger wing of the birthplace. By the time he was six he joined the older children in sticking wire teeth into strips of leather for carding cotton. Making easier the monotonous drudgery, there was a genius in the place architectonic with invention. The buzz of mill wheels filled the air in which Elias became acquainted with the elements of machinery, so far as known, and with machine tools. He absorbed an atmosphere kinetic with ingenuity. In 1866 he told James Parton that he was of the opinion that this early experience gave his mind its bent.

After five years of this struggle, as early as eleven, his Spartan father “bound him out “in 1830 to a neighboring farmer till the time of his apprenticeship should be over and he could return wearing his “freedom suit.” But he was inclined to lameness from his birth, and he returned at twelve to stay home till sixteen.

The biographer, James Parton, who knew Howe so well, describes him, while congenitally lame, as a regular boy, curly headed, though a bit undersized, fond of jokes, and not over able or over fond of grinding from candle light to candle light on a hard-scrabble farm. Later he must have outgrown some of these traits, as his daughter, Jane R. Caldwell, wrote to me from New York, September 28, 1909, as to Parton’s descriptions as follows: “My family and I are far from satisfied with the impressions given of my father’s early life and character, which was full of purpose.” However, Parton was right in his general psychoanalysis of his friend. Each of these characteristics could be true, one of the natural fun-loving human boy, the other of the controlled man chastened by suffering and responsibility and struggle. One would think more of him because he was no abnormal, mechanical crank, but thoroughly human.

In 1835, four years after his return home, he drifted to Lowell where he had heard of the vast cotton machine shops. But the sixteen-year-old mill hand lost his place in the panic of 1837. Then the “bobbin boy,” N. P. Banks, his cousin, and later governor, Speaker of the House and Civil War general, took Elias’ arm and drew him to Cambridge to a hemp-carding machine shop of a Professor Treadwell. The two boys in greasy jumpers and overalls worked side by side and roomed together.

At this critical age of awakening, no doubt Banks’s aspirations could not but have been creative of ambition in Elias. From this time too, William Howe, the landlord of the sleepy tavern, who awakened just before 1840 to his inventive dreams of bridging the streams of the world and carrying railways on his spans through Europe, must also have stirred the imagination of Elias.

The Vision Of A Sewing Machine

At 18, late in 1837, Elias Howe as journeyman entered a machine shop at 11 Cornhill, Boston, kept by Daniel Davis. Howe’s employer manufactured optical instruments and was noted as a skilled repairer of intricate mechanical inventions. Elias himself made little improvements and worked at a bench and lathe, often hearing snatches of conversations of inventors who came in to talk over their half-finished machines.

After three years at the machine shop, in 1840, he was only getting $9.00 a week. But he married, on this salary of a dollar and a quarter a day. To support the wife and the family of three children coming on, one after another, put the boy husband under pressure. It almost crushed him. After work he was hardly able to get up from the bed upon which he threw himself supperless and worn, only wishing, as he told James Parton afterward, “to lie there forever and ever.” In 1842, when Howe was now twenty-three years old, and had been in the shop five years, there came in an inventor of a little knitting machine that would not work. With the inventor was a promoter of the machine, the man who was his financial backer. Mr. Asa Davis, brother of Daniel, explained his plans were not complete, but he would make the model when perfected.

“Why don’t you make a sewing machine?” asked Asa Davis, dissuading the man from wasting his time on a knitting machine.

“It can’t be done,” snapped the financial backer.

“Yes, it can. The man that can make a machine that will sew, will earn his everlasting fortune.”

When Howe went home to Cambridge that night, his untapped reservoirs of inventive energy were pierced. No longer dormant from exhaustion, he mused upon the declared impossible invention. He could not dismiss the challenge from his awakened mind till his ingenuity grasped at an idea. “Thomas,” he exclaimed the next morning to his fellow journeyman mechanic at the next bench and lathe, “I have gotten an idea of a sewing machine!”

In the meantime Howe’s wife took in sewing to eke out. Lying supperless in bed after the exhausting day’s work, his eye saved him from dropping off by following the motion of her arm. He was trying to discover a way to imitate it in an arm of wood and steel. What he would save if he could! He often imitated Mrs. Howe’s arm movements. The mania of invention seized him deeper and deeper and would not let him rest. Thence, day and night, he aimed to materialize the ideas burrowing in his inventive imagination. Then in 1843 he set to work to make a machine to take the place of the human hand. Night after night he whittled upon models till morning. Nothing but piles of whittlings were the result. It would not work.

The Crisis Of The Invention — The Needle With An Eye At The Point

He was halted at the needle’s eye. Should it be a needle pointed at both ends with the eye in the middle, working up and down, thrusting the thread through each time? Through many nights of experiment he tried it. No — it would not work!

Then why not another stitch using two threads, a shuttle and a curved needle? But where pierce the eye in the needle? Why not try it at the front end?

He cut coils of wire. He grooved them on one side with a pair of steel dies. He left in the middle a raised edge. With highly tempered steel at the needle’s end, he drilled an eye. Then he inserted it in the crude whittled model. His contemporary, Parton, describes the moment thus: “One day in 1844, the thought flashed upon him — is it necessary that a machine should imitate the performance of the hand? May there not be another stitch? Here came the crisis of the invention, because the idea of using two threads, and forming a stitch by the aid of a shuttle and a curved needle with the eye near the point soon occurred to him. He felt that he had invented a sewing machine. It was in the month of October, 1844, that he was able to convince himself, by a rough model of wood and wire, that such a machine as he had projected, would sew.”

The miracle of the sewing machine was achieved!

There is a remarkable letter which I have discovered from the living eyewitness and coworker on the original model. It is one that catches the invention at its birth from the worker at Howe’s elbow on the next lathe at the very hour of invention. It has lain in the hands of Dr. Alonzo Bemis of Spencer. It is as follows:

Dec. 8, 1910.

Madisonville, Ohio.

Dr. Alonzo A. Bemis.

Dear Sir:

Probably I am the only man living who was with Howe when he invented it (the sewing machine) and worked on the model. In the year 1839, I went to work for Daniel Davis, philosophical instrument maker, at No. 11 Cornhill, Boston, Mass. Mr. Davis was the father of Daniel Davis, of Princeton. Elias Howe was then working for Mr. Davis as a journeyman. His bench, and lathe, was next to mine. Mr. Davis’ shop was headquarters for all kinds of geniuses, inventors, etc. One day there came a man into the shop who wanted Davis to make a knitting machine. Mr. Asa Davis, brother of Mr. Daniel Davis, talked the plans over and said to the man: “Your plans are not complete. Perfect your invention and I will make the model.” Asa remarked that if anybody could make a good, practical sewing machine a woman could use, there would be a fortune in it. That remark stuck in Elias’ head. The next morning, he said to me, ” Thomas, I have gotten an idea of a sewing machine.”

Howe did not rest until he perfected the machine. He made a very coarse model but in that model was the embryo of all the sewing machines made to this day, and that was, pushing the eye of the needle through the cloth, instead of the point. In my leisure moments, I would work the machine with Howe. Everybody discouraged him. We found great trouble in passing a thread through the loop so as to lock the thread. When he conceived the idea of a shuttle, the sewing machine was practical.

Yours respectfully,

THOMAS HALL (85 yrs. old)

“I should like,” adds Dr. Alonzo Bemis, “to correct an error which has found its way into the press on many occasions — that is: that the idea of the needle came to Elias Howe in a dream. This is not true. Mr. Howe was too much of a Yankee to place any dependence in dreams and the needle idea was worked out by careful thought and countless experiments.”

After working upon the model, assisted sometimes by his fellow-mechanic, Thomas Hall, who tells us of it so interestingly, Howe found the increasing toil and increasing family and increasing expense upon the model too overwhelming a burden. With no money at hand to develop his invention, he turned to his father.

Elias Howe, Sr., had by this time left Spencer and moved to Cambridge. The inventive ingenuity of Tyler Howe, the one of his brothers who later invented the spring bed, had invented a system of cutting Palm Beach leaf for hat manufacture. Elias Howe, Jr.’s father, came to conduct the factory. This factory was at 740 Main St., Cambridge, below Lafayette Square. This “incubator of invention” is still standing, a plain three-story brick affair. It was then called the Palm Beach Hat Factory, later Howe’s Spring Bed Factory. It has been a very nest of genius. Here the three Howes carried into materialization their developing dreams of the truss bridge, the spring bed, and the sewing machine. Here at times Morse worked on the telegraph, and Elias Howe made batteries and magnets at $1.25 a day. Here Graham Bell, after 1872, struggled with the invention of the telephone; and here John McTammany, who was working on the voting machine and the pneumatic tabulating system, disclosed his vision to invent a player piano, and with the inventor’s urge came from the Howes’ home at Spencer and worked it out.

Into his father’s house in Cambridge in November, 1844, Elias Howe, Jr., removed his family and put his lathe and few machinist’s tools into the garret, where he worked desperately hard, concentrating himself upon the model, yet rough and coarse. For the design must be made, he knew, into “iron and steel with the finish of a clock.” At this time the Palm Beach factory burned out, and Elias Howe, Jr., with an invention in his head ready to revolutionize the world’s industry, was blocked.

Here crops up an old Spencer friend, George Fisher. He was a schoolmate. Now he was a small coal and wood dealer in Cambridge. But in December, 1844, Fisher asked Howe with his family into his own house, and let him put his lathe under the slanting eaves in the garret. Besides, he loaned his old Spencer schoolmate $500 for which he would receive one half interest in the patent, if successful. He was one of the unknown soldiers of invention, the romance of whose chivalry was equal to that of the Yale friend who financed, and at the cost of his life saved, Eli Whitney. “I was the only one of his neighbors and friends in Cambridge that had any confidence in the success of the invention,” Fisher declared. “Howe was generally looked upon as very visionary in undertaking anything of the kind and I was thought very foolish in assisting him.”

To this centennial celebration, October, 1919 — to this house on Brattle Street where Worcester wrote the Dictionary —has come a lady, the daughter of this chivalrous friend, to confirm the facts of his friendship.1

Winter passed. But here by April, 1845, the steel model grew into form. The needle shot through the cloth, sewing a perfect seam. By May it was complete, and in July he sewed two suits of clothes.

To be continued next week…

This article can be found in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society Volume 14, from the year 1919.