Growing Up on Worcester Street

By Suzanne Revaleon Green

Originally published in A City’s Life and Times: Cambridge in the Twentieth Century, 2007

Introduction written by Paula Paris, a member of the Cambridge Historical Commission and a co-founding member of the Cambridge Black History Project, an all-volunteer organization of individuals with deep roots in Cambridge, committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving, and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments, and challenges of Black Cantabrigians.

INTRODUCTION

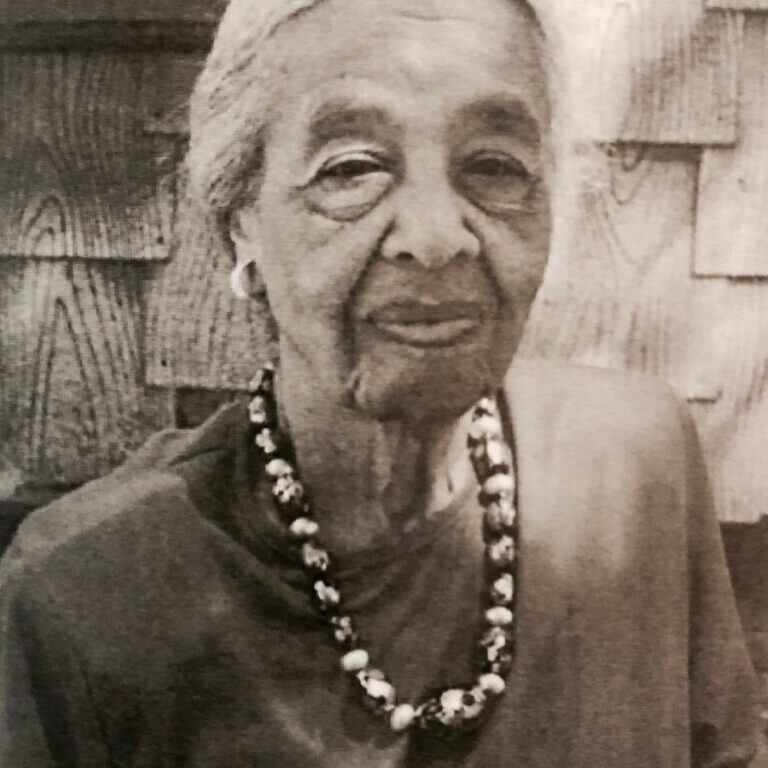

Brilliant, eloquent, strict, caring, dignified, dedicated, revolutionary – some of the words often expressed to describe Suzanne Revaleon Green by those who knew her.

I had the pleasure and privilege of meeting the warm and gracious Mrs. Green as a Cambridge neighbor, briefly in the mid-1970s. I remember her apartment, clearly downsized from an entire household, was appointed with treasured objects of a life well-lived. She did not speak about herself except to say that she had also graduated from Cambridge High and Latin and had been a teacher in Cambridge for many years. She was most interested that I had also graduated from the high school and was in graduate school at the time. Our conversations were few. It wasn’t until many years later that I became aware of the depth and breadth of her accomplishments and contributions, including blazing the trail for female teachers of all colors to continue their careers after marriage.

That story is well-documented and chronicled in many articles and volumes such as Frank Dorman’s Twenty Families of Color in Massachusetts, Daphne Abeel’s Cambridge in the Twentieth Century, and the Cambridge Women’s History Project. Her honors include the first Margaret Fuller Lifetime Achievement Award, YWCA 17th Annual Tribute to Outstanding Women, and Outstanding Educator Award from her alma mater Salem State College. She was given a key to the city on her ninetieth birthday.

Suzanne Revaleon Green was a fifth generation Cantabrigian, scion of two families with long, storied New England lineages going back to the 1700s. The Revaleon family history includes early membership in the Prince Hall Lodge; family relationships with the historically important Howard family, as well as Wampanoag, Massasoit and Nipmuc families; and Civil War military service. Her grandmother was a descendent of the Lewis family, noted abolitionists, several of whom established the Lewisville community of Cambridge in the 1800s.

Mrs. Green taught at the Houghton and Roberts schools. She volunteered for the Girl Scouts, Cambridge Community Center, the YWCA, the Cambridge Historical Commission, and was a co-founding member of the Cambridge African American Heritage Trail.

She was dedicated to her students, her neighbors, and the history of her beloved hometown. Her impact has been far reaching. “She was the most important person on our street,” remarks a former neighbor. One of her students recalls how she tutored him on her own time on Saturdays at her house. And a former colleague commented, “We – and the citizens of Cambridge – were and are better for the contributions she made to the Historical Commission and to the broader civic life we share in Cambridge.”

The following article introduces Suzanne Revaleon Green to a new generation of “kids from Cambridge,” helping to perpetuate the rich legacy she has left our City.

Just before the beginning of the twentieth century, my nanna’s husband-to-be bought a house on Worcester Street as a wedding present for his bride. It was especially good for him because the barn behind the house would be fine for his horse and wagon. He was a dealer in fruits and vegetables.

My mother had grown up on Worcester Street and had graduated from the Harvard Grammar School, which is now the City Hall Annex at the corner of Broadway and Inman streets. Her next graduation was from English High, later Cambridge High and Latin and now Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. She had attended Sunday school at the Harvard Street Methodist Church, now St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, only a block and a half away from where she lived. When she married, her husband, my father, lived on the North Slope of Beacon Hill, but they decided to make their home on Worcester Street also, and they moved into their three-room apartment.

I was their first child and grew up in a friendly, mixed neighborhood. My mother, who stayed at home, often made hats and dresses for her friends and neighbors. There were many children in the neighborhood, and we spent many hours playing together. With the help of our next-door neighbor, a retired Irish carpenter, my father built me a playhouse in our yard. Parts of its construction came from the demolition of some beautiful old houses on Norfolk Street, where new apartment houses were being built. As a little girl, I can also remember standing in our bay window at dusk to watch the lamplighter ride up the street on his bicycle to light the gas lamp at the corner of Norfolk and Worcester streets.

Early one February morning in 1918, when I was six years old, the stork brought me a new baby brother. After a frantic telephone call made by my father, Dr. Lockhart arrived quickly from his home on Massachusetts Avenue, near Bigelow Street.

I walked to the Fletcher School on Elm Street each day and went home for lunch, returning to school within an hour for the afternoon session. We all attended our nearest neighborhood schools. At the Fletcher School, the auditorium was on the top floor, and for my first two years, during World War I when coal was often hard to get, the building was not warm. Students from all the classes climbed the stairs to the auditorium to sit together on wooden benches, to sing songs and feel warm.

The day the Armistice was signed was a wonderful day. We went up to the auditorium, sang one or two patriotic songs, pledged allegiance to the flag, sang “The Star Spangled Banner,” and were dismissed early.

When I was in the third grade, my teacher was Miss Gertrude Baker, the second African American teacher in the Cambridge schools. She followed the renowned Maria Baldwin, who in 1882 had been appointed a teacher and in 1889 became headmaster at the Agassiz School, which was recently renamed the Maria Baldwin School in her honor. In 1937 I became the seventh African American teacher in the Cambridge schools with an appointment at the Houghton School, now the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. School on Putnam Avenue.

There were so few cars and so little street traffic on Worcester Street that our quiet one-block, tree-lined street was a safe playground for our after-school play. We all had metal roller skates that we clamped onto our shoes with a metal key. Up and down the street we’d skate, sometimes with a best friend, sometimes with a group. Then, often, we’d put the skates away and play Hide and Seek. The telephone pole served as “home.” The last person to call out a name would be “it.” While that person closed his or her eyes at the post and counted, perhaps to twenty, everyone else would run and hide, behind fences, trees, steps, wherever, hoping to have a chance to dash over to tag the pole before being tagged themselves. The last person caught became “it” for the next game.

The boys liked to play marbles, and they usually kept a supply of the many-hued glass orbs available. Down on their knees or crouched over a little hole in the ground, they would aim to knock the others’ marbles out, thereby increasing their own holdings.

On a warm summer’s day, many of the boys and girls walked down for a swim at Magazine Beach, not far from Brookline and Magazine streets on the Charles River, where there was a sandy bank. Everyone could enjoy a swim. The Magga, as it was called, has been closed now for years because of the pollution in the river. But cleanup efforts are planned.

Mid-day on Saturdays, neighborhood boys and girls would be found lined up in Central Square waiting for the movie theater to open. For an entrance fee of ten cents, they would see the news of the day, sports, a cartoon, and the movie, which was usually a serial that left the heroine in a most life-threatening situation. The next week, however, she would be back, hale and hearty, to carry on until the next week’s climax.

The Central Square was the largest neighborhood theater, with padded theater seats and a large balcony. Sometimes in the evening there would be a stage show and free dishes or other gifts to encourage attendance. A much smaller movie house stood near Lafayette Square. The Olympia Theatre, better known as the “Olymp,” was opposite the police station in Central Square, in a long, narrow block. It was not considered clean and well-cared-for, but it showed serials and westerns and had its own regular patrons.

During the month of May—and only during May—there were May parties. The child giving the party would be the Queen, her best male friend the King, or the other way around. Tissue papers in pastels, a bit heavier than the tissue paper now used for wrapping, was sold at our corner stores for a penny a sheet. That, cut and braided with streamers, became our May Party headpieces. The girl hostess wore a gold paper crown, as did her escort. Often a half-circle hoop, covered with pastel papers and with streamers, provided an arch under which the children paraded around the block followed by their friends, all wearing headpieces, singing—or chanting, really—all the way:

May Party, May Party

Rah, Rah, Rah,

Who are we?

We are the Worcester Streets

Don’t you see?

Are we in it?

Well, I guess we are

Two, four, six, eight

Who do we appreciate?

Mary, Mary, Mary (the name of the hostess)

Rah, Rah, Rah.

At their return to the yard of the hostess or host, games were played, punch and cookies were served, and the May Party was over.

Days before the Fourth of July, my brother and I would walk with my father to the little store on Essex Street to buy firecrackers, sparklers, and Roman candles. The tiny firecrackers and the sparklers would satisfy me. My brother usually chose the big firecrackers and the Roman candles that shot off like rockets. Only later did I realize how dangerous they were and how much safer it was for everyone when fireworks were made illegal. Picnics became a much more enjoyable means of celebrating the national holiday.

Often our street would become a baseball field, with several rocks providing bases. A bat, a baseball, and a few gloves were all that were needed. The constant hope was that no neighbor’s front window would fall victim to a strong hitter.

The girls liked hopscotch. We would draw a diagram of the hopscotch boxes on the pavement with a piece of chalk, which probably had come from school. Turns were taken tossing the little stone and hopping through, skipping designated squares. Even mothers joined in once in a while.

One noisy sport enjoyed by the boys required the acquisition of a wooden orange crate and roller-skate wheels. The addition of a handlebar provided a means of steering and called for a bit of engineering.

In the winter, snow usually stayed where it fell, and we’d all bring out our sleds. Smaller children were pulled around on their little sleds by indulgent older brothers and sisters. Flexible Flyers were the favorites of the older boys and girls. If you ran fast enough and fell down fast enough onto your Flexible Flyer, the moment carried you several yards, with the steering bar making it possible to choose your course.

All our news came in print. Along with the regular morning edition of the newspaper, there was an afternoon edition for later news. If there were some really noteworthy happenings, an extra edition would be published quickly. Then newsboys would go through the community shouting, “Extra, Extra,” to sell the later edition. Thus on April 19, Marathon Day, we would await the extra edition to learn the name of the Marathon winner, which for a number of years always seemed to be Clarence De Mar.

Loaves of bread wrapped at the bakery could be bought at the grocery store and brought home to be sliced. It was an exciting time when the bakeries began to provide loaves already sliced.

Exciting, too, was the discovery that ice cream could be bought in packages at the grocery store, made possible by electric refrigeration. Before that, ice cream could be had only at the ice cream store, kept cold by means of real ice. As the packaging got better, the taste and quality improved.

Few families had radios, and television was yet to be invented, so there was little to keep us in the house after we’d come home from school and finished our homework. On stormy days, our only means of discovering whether or not there would be school was to listen for the big fire whistle to blow at 7:30 A.M. Somerville had the same method, and since the two cities are so close, by agreement both closed on the same stormy days.

We were all so proud when our father, following the directions he had, made a radio by winding small wires around a big round oatmeal box. There was a special spot where one wire had to be touched by another wire called a cat’s whisker. We put on our earphones and could hear music for fifteen minutes, followed by a pause of five minutes, then fifteen minutes more of music. The source of this magic was the old Shepard Store on Tremont Street in downtown Boston, the location of Boston’s first radio station, WNAC.

In the 1920s the horse and wagon were an important part of life in Cambridge. That was how we received our daily supply of milk and cream early each morning, left on our back doorstep. If the day was very cold and we were slow in taking it in, the bottle of milk might have a stovepipe hat; the cream would rise to the top, freeze, and push the cap up. Homogenized milk had yet to be invented.

The ice man brought huge cakes of ice on his wagon. His nine-by-nine-inch card in our front window would tell him the size of the pieces we needed by its position. He would cut the piece, carry it on his back into our kitchen or pantry, and use his huge tongs to place it on top of our oaken ice chest.

The fresh fish man came on certain days, and always on Fridays. The vegetable man also had a regular schedule. But most spectacular of all was the ragman, who rode through the streets calling, “Rags, rags, any old rags.” He bought old newspaper, too, paying a few cents a pound for each.

In the winter, since it was before the days of snow plows and plowed streets, the wagons with wheels were put away and out came the pungs, wagon bodies with sleigh runners. Snow and ice was then no obstacle.

Angelina was a man most eagerly watched for in the summer. He was short and brown-skinned and wore a big straw hat and a white coat and sang his song of cold ices. He had a big cake of ice and many bottles of colorful fruit syrup on his little pushcart, from which he would add your choice of syrup to a cut of scraped ice. It was a refreshing break on a hot summer day.

The coal stove that provided heat for the kitchen and for all our cooking was shiny black. In the winter the fire was kept burning night and day. It also heated the handsome, tall copper boiler that contained our hot water supply. The boiler was kept polished to a shine, along with the brass faucets and the piping over the sink and washtub.

Our regular schedule called for fish for Friday night supper. On Saturday, it was baked beans, brown bread, and frankforts. Except in the summertime, the brown, glazed-clay bean pot spent the entire day in the oven, having been put there in the morning by my nanna, who filled it with parboiled navy beans, molasses, a piece of salt pork, and spices. The flour, molasses, raisins, and spices for brown bread were placed in the round metal container with the tight top and boiled for hours in a pot of water on top of the stove.

Central Square was once the focal point of Saturday night shopping, not only for Cambridge residents, but also for those from neighboring communities.

There were large stores and small stores. Our big market was the owner-operated Manhattan Market, with a sales person behind every counter to bag your purchase and accept your payment. Grants, the Lincoln stores, Enterprise, Kresge, Woolworth’s, and others supplied the needs of our households over the years. Woolworth’s, which had started as a five-and-ten-cent store, was the last to leave.

Many small stores lined Massachusetts Avenue and the small adjoining streets. There were bakeries, barber shops, confectionery stores, butter and egg stores, fish markets, florists, tailors, shoe stores, jewelry stores, even a furniture store. Saturday night shopping ended quickly with the advent of motor cars and the attraction of the new shopping center.

These are my early memories of growing up on Worcester Street.

Suzanne Revaleon Green, born in 1912 to James Albert Revaleon and Ruby Higginbotham, was a lifelong resident of Cambridge She lived at 9 Worcester Street, the house in which she grew up.

More information on Green can be found at Cambridge Women’s Heritage Project: https://www2.cambridgema.gov/Historic/CWHP/bios_g.html#GreenSR