The Blake & Knowles Steam Pump Works in East Cambridge: The Female Foundry

By Sarah Huggins, Lesley University Intern, May 2020

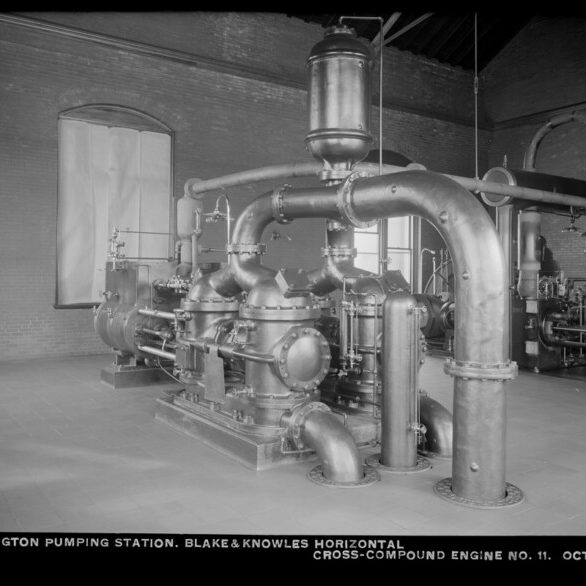

Designed in 1890 and in operation until 1927, the Blake & Knowles foundry building still stands in East Cambridge at 101 Rogers Street in Kendall Square, harkening back to an area of Cambridge that was historically one of heavy industry. In recent years, the Blake & Knowles Steam Pump building has been refurbished by the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority with the goal of community use. The building is currently vacant despite hopes that it would provide a multipurpose center for displaying art and promoting entrepreneurship, technology, and workforce education. A visitor to the building may note its architectural significance as a symbol of industrial development, while never realizing the associations the structure has with women’s labor history and the substantial role of Cambridge women in the workforce.

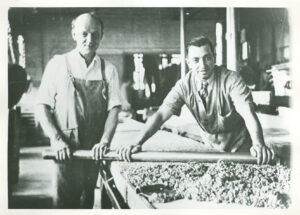

In the autumn of 1911, the women workers employed by the East Cambridge Blake & Knowles steam pump company were the subject of great controversy and debate. These women, many of whom were Polish immigrants, toiled alongside men in the foundry. A report from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) found that the women workers of the foundry were, “Working with their charred and grimy bodies bared to the waist, in a heat unbearable at times, and for an indefinite number of hours, scarcely able to obtain sufficient time to gulp down a coarse, un-nutritious noonday meal.” The women employed by the Blake & Knowles Steam Pump company in the making of iron cores were deemed to be faced with “a task far too taxing for the delicate constitution of a woman.” Newspaper articles with the aim of drawing the public’s attention to “help” these women workers of East Cambridge, made it clear that the women were “at times scantily clad.” As maintained by the legacy of Victorian gender norms, the thought of shirtless women and men laboring next to each other was a horrific one. Prior to the First World War, it could be estimated that there were, at most, a few hundred men working in the foundry and plausibly more than twenty-six women. The newspaper articles and the AFL report created, to put it lightly, an uproar to “protect” the foundry women by passing a bill for the non-employment of women in foundries. There is, however, no evidence that women foundry workers were forced into their positions against their own will.

On the night of September 25th, 1911, Governor Eugene N. Foss declared himself in favor of state police intervention, a raid, to reveal the “unsanitary” working conditions of the iron foundry women of East Cambridge whose work exceeded the legal limit of a 54 hour work week imposed on women workers. The mayor of Cambridge supported this raid, which was likely set in motion because of complaints from male foundry workers who voiced opposition to their female foundry co-workers seeking more hours. General Manager of the foundry, George P. Aborn responded, “Our women are strong, and fully capable of doing the work which is required of them, and the company issues a garment which they wear over the street clothes.” The Governor’s investigation ultimately led nowhere, as there was no evidence of a violation of existing law at Blake & Knowles. Yet, in 1912 Massachusetts passed the Employment of Women in Core Rooms (to regulate the structure and location of the rooms, the emission of gases and fumes from ovens, and the size and weight which the women shall be allowed to lift or work on) and the nation’s first minimum wage law, which only applied to women and children workers, effectively locking them in to low pay without the ability to negotiate. Were these laws a direct response to the non-traditional women foundry workers of East Cambridge?