Reclaiming William Wells Brown, an abolitionist, lecturer, author and doctor with Cambridge ties

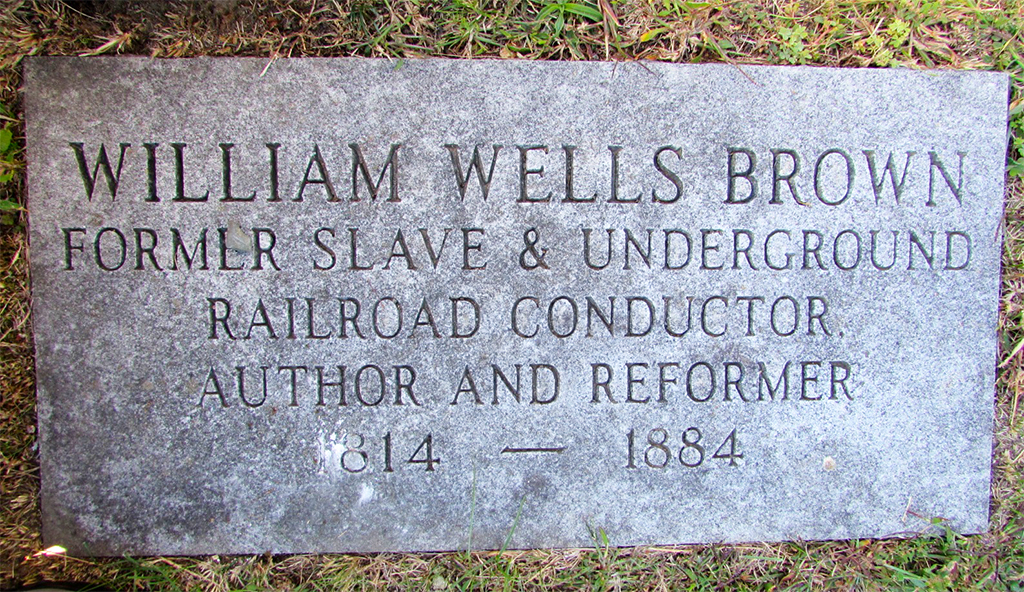

Above image: William Wells Brown’s grave in Cambridge Cemetery. (Photo: History Cambridge)

By Beth Folsom

The recent unveiling of a mural on a restaurant in Easton, Maryland, has raised questions about the link between historical figures and contemporary culture. The painting of Frederick Douglass, a favorite son of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where the mural is located, depicts the famed abolitionist and orator dressed in a modern suit and sporting a contemporary wristwatch and Converse sneakers. This “update” of Douglass’ style has elicited a variety of responses, from disapproval of what some see as a lack of respect for Douglass’ position in 19th-century history to a hope that this recasting of Douglass’ look will engage a new generation of viewers with his story.

While Douglass has long been the most famous Black American antislavery activist, there are many others whose stories are just as compelling, if not as widely known. One such abolitionist was William Wells Brown, whose travels in support of an immediate end to enslavement and for equal rights for Black Americans brought him around the country and across the Atlantic, and ultimately to Cambridge.

Brown was born on a plantation near Mount Sterling, Kentucky, in 1814. Born to an enslaved mother, Elizabeth, and a white father, George W. Higgins (the cousin of his enslaver, Dr. John Young), his given name at birth was William and, as far as the historical record shows, he did not have a formal surname as a child. Higgins acknowledged William as his son formally and made Young promise not to sell him, but Young disregarded that promise and sold both William and Elizabeth.

By the time William was 20, he had been sold several times, spending the majority of his youth in St. Louis, where he was hired out by his enslavers as a deckhand on the steamboats that transported goods and human property up and down the Missouri River. His work enabled him to become familiar with the geography of the region and to form relationships with other enslaved and free Blacks, as well as with whites supportive of an end to slavery. In 1833, William and his mother escaped together across the Mississippi River, but they were captured in Illinois. The next year, William made a second escape attempt, successfully slipping away from a steamboat when it docked in Cincinnati, Ohio, a free state.

After claiming his freedom, William took on the name of Wells Brown, a white Quaker who had provided him with food, clothing, and money after his escape. He soon went to work for Elijah P. Lovejoy, assisting the prominent abolitionist at his printshop. Brown married Elizabeth Schooner, and the couple had several children, two of whom survived to adulthood.

In 1836, Brown moved to Buffalo, New York, where he worked as a steamboat man on Lake Erie, using his position to help enslaved people escape to freedom in Buffalo, Detroit or across the border to Canada. Brown became active in the abolitionist movement in Buffalo, where his gifts as an orator were quickly recognized. In 1849, he traveled to England to give lectures on the abolitionist circuit; when the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (which mandated that those who had escaped enslavement be returned to their enslavers – by force, if necessary), Brown and his supporters agreed it was safer for him to stay in England until his British friends bought his freedom in 1854. The same British supporters bought the freedom of Douglass.

Upon his return to the United States, Brown gave speeches and engaged in abolitionist work in New York and Massachusetts. He had published his first book, an autobiography of his early life under slavery and his escape and early career, in 1847, and he followed that with a number of written works during his time in England and after his return to America. His most famous work, the novel “Clotel, or the President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States,” was the first published novel by a Black American author when it debuted in 1853.

In 1860, after Elizabeth Schooner’s death, Brown married Anne Elizabeth Gray, the sister of William Gray, a Black Cambridgeport caterer who later served in the Civil War. The couple moved into a house on Webster Avenue and Brown began to study medicine. He also helped Douglass recruit for the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, an all-Black regiment serving in the Civil War.

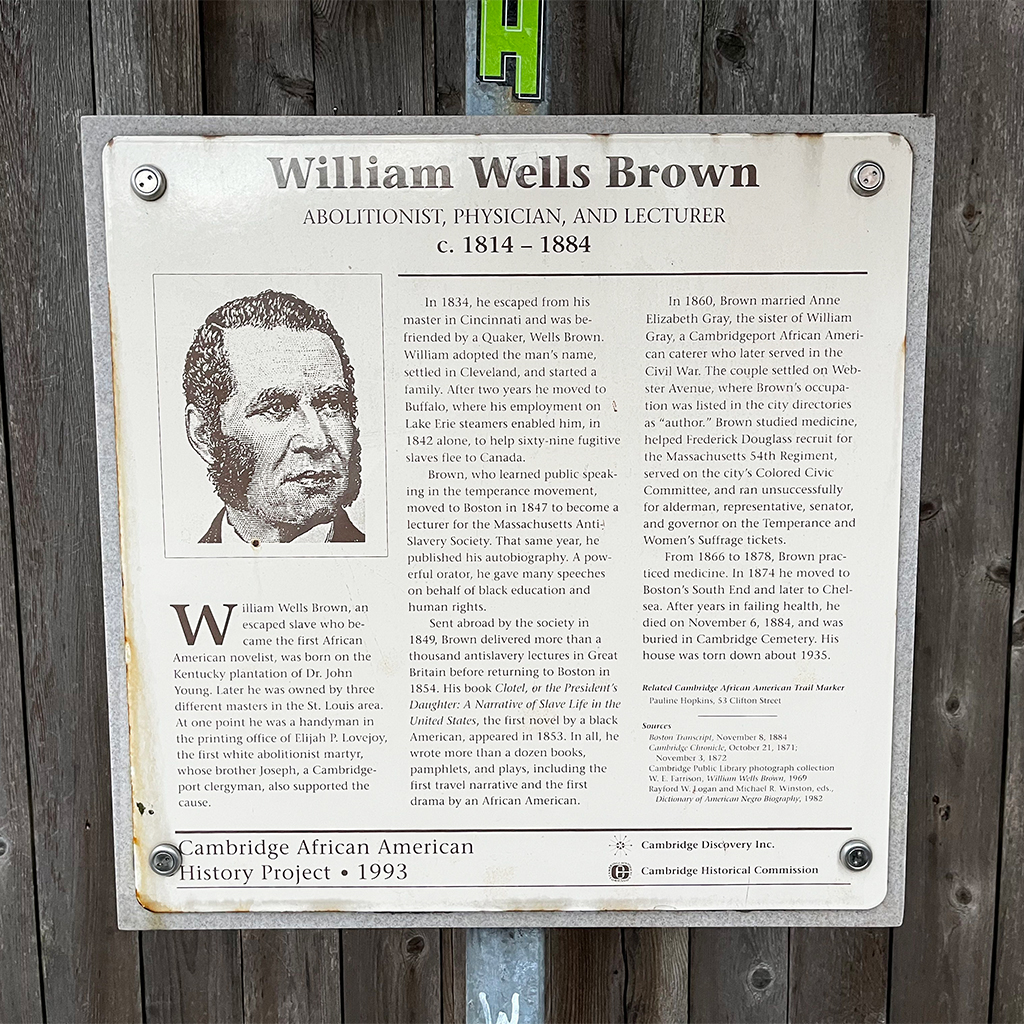

From 1866 to 1874, Brown was a Cambridge resident practicing medicine in Boston. Then he moved to Boston’s South End and later to Chelsea, where he died in 1884, bt was buried in Cambridge Cemetery. His house in Cambridge was torn down in 1935, but a marker was erected on its site in 1993 as part of the Cambridge African American History Project. Although historically overshadowed by Douglass and other prominent abolitionists, Brown’s legacy has recently received more attention from scholars and public history sites, including the Erie Canal Museum, whose program on Brown’s life and activism can be viewed online. Brown’s career as an orator, writer, doctor and activist helped to connect Cambridge to the broader social and political forces sweeping the country in the mid-19th century, and reclaiming his legacy helps the city to broaden our understanding of the important work being done locally by and on behalf of Black Cantabrigians.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.