Andrew Craigie: Mover and Shaker of East Cambridge

by Daphne Abeel

Craigie Street, just to the west of Harvard Square, memorializes Andrew Craigie (1754-1819), but his most significant legacy is his development of East Cambridge. He also arranged to move the courthouse and the jail from Harvard Square to East Cambridge. That move, combined with his building of the Canal (or Craigie) Bridge from Lechmere’s Point to Boston, assured that East Cambridge would prosper and grow, eventually becoming a center of commerce and industry.

The descendant of a Scottish sea captain, Craigie began his life in Boston. He received some medical training and was appointed First Apothecary General to George Washington’s army. He also made many important business connections that served him well when he began a career of land speculation and development.

Settling in Cambridge, he began land speculations and was soon the owner of Lechmere’s Point, a parcel of 300 acres. These acquisitions were made shrewdly and secretly, mainly through the offices of his relatives and friends.

One of his more significant purchases in 1792 was the Henry Vassall house, known today as the Longfellow House. Craigie’s first major project was the Canal (or Craigie) Bridge and toll house in 1809. Craigie also supervised the laying out of major roads, including Cambridge Street. These roads attracted business, and the bridge to Boston assured commercial activity through East Cambridge. Eventually, many businesses, notably glass making and candy manufacture, would be established in the area.

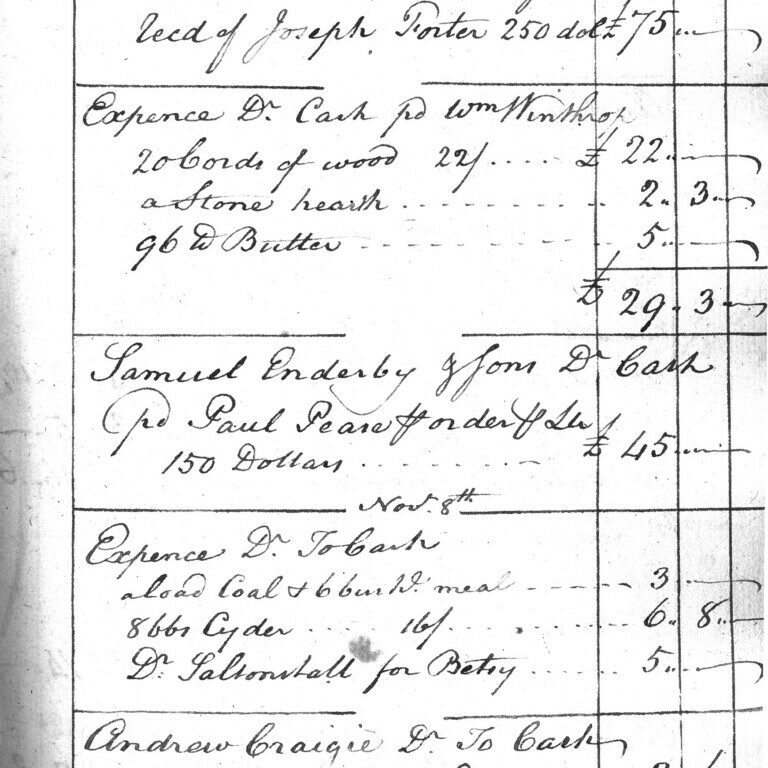

Despite his entrepreneurial talents, Craigie was not liked by many of his fellow townsmen, some of whom had invested in a competing project, the West Cambridge Bridge. And many saw his efforts to move important institutions from Harvard Square to East Cambridge as destructive and disruptive. While Craigie did more to reconfigure the map of Cambridge than anyone of his time, the War of 1812 and speculation financed on credit led to the failure of his business ventures. He fell so deeply in debt that he lived in fear of being arrested and sent to prison. When he died of apoplexy in 1819, he was bankrupt. His wife was forced to sell her belongings and take in lodgers, one of whom was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

There was a murky side to Craigie’s personal life, which came to light when Alice Longfellow discovered a packet of letters from a certain Polly Allen hidden in a niche below a staircase. Although they were addressed ‘‘Dear Uncle,’’ it became clear that they were from a daughter born out of wedlock, the result of a liaison Craigie had enjoyed with a Quaker woman when he was stationed with Washington’s troops in the Philadelphia area.