Self-Guided Tour: Monuments and Memorials in Cambridge

Cambridge is a city filled with monuments. Statues, plaques, and memorials across the city commemorate people and events from its nearly four hundred years of settlement. But who decides what is worthy of commemoration, and how does the memorial landscape of the city reinforce certain narratives of Cambridge history and exclude others? In this tour we will visit several of the many monuments in the city, examining not only the subjects they commemorate but also what they can tell us about the society that created them.

John Harvard Statue (Harvard Yard)

John Harvard did not found Harvard College, as many believe, but was instead a clergyman who gave a large donation (money and his library) to the College’s endowment on his deathbed. The statue was sculpted by Daniel Chester French in 1884. There is no known record of what John Harvard looked like, so French used a Harvard student (said to be a descendant of an early Harvard president) as a model. French would go on to create the statue of Abraham Lincoln for the 1922 Lincoln Memorial in 1922, but by the time of the John Harvard statue he was already well-known in Massachusetts as the sculptor of the Minute Man statue in Concord (1874).

The statue of John Harvard was donated by Samuel Bridge, a descendant of John Bridge who also financed the John Bridge “Puritan” statue on Cambridge Common. The books featured in the statue (open on his knee and stacked under his chair) refer to his donation of over 400 works to the college library. It is commonly referred to as “the statue of three lies”: the base says “John Harvard,” but it is not, in fact, his likeness, since none is known to exist; “founder” is also a misnomer, as Harvard was not the founder of the college but rather an endower; finally, the date on the statue of 1638 does not, in fact, refer to the College’s founding (1636) but rather to the year of John Harvard’s death and subsequent bequest. Visitors may notice that the statue’s left foot is shiny because tourists rub it for luck – another misconception that this is a student tradition.

Civil War Memorial (Cambridge Common)

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65675414/shutterstock_482297266.0.jpg)

Dedicated in 1870, the original monument was designed by brothers Darius and Cyrus Cobb, who were both artists and Civil War veterans. The memorial is topped by a statue of a Union soldier, one who is meant to symbolize the common man who fought in the war. In 1910, a statue of Abraham Lincoln was added inside the stone niche in the center of the monument. Sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the statue was a casting of his earlier statue of Lincoln, copies of which are also on display in New York, London, and Mexico City. The base of the memorial features a number of bronze plaques, including a dedication to fallen Union soldiers and sailors, and the text of both Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and General Orders No. 1, which established Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day).

Charles Sumner Statue (Harvard Square)

Sumner was a Senator from Massachusetts and the leader of the Radical Republicans, who advocated for immediate abolition of slavery. He was also a Harvard alumnus. In 1856, Sumner insulted two Democratic Senators on the floor of the Senate for their support of slavery, including Andrew Butler of South Carolina, who was not present when Sumner made his remarks. Butler’s cousin, Representative Preston Brooks, beat Sumner with his cane on the Senate floor, causing permanent injury. Brooks was censured by Congress, but went on to be reelected before his early death.

Sculptor Anne Whitney’s design was the winning selection following Sumner’s death in 1874, but the committee ultimately rejected her design once they found out that she was a woman. They chose Thomas Ball’s design instead, and that sculpture is installed in the Public Garden. In 1902, an anonymous donor allowed Whitney to resurrect her design, and her statue was installed just outside Harvard Yard.

Irish Famine Memorial (Cambridge Common)

The memorial was created in 1997 to mark the 150th anniversary of the Famine, a multi-year failure of the Irish potato crop caused by blight. Between 1845 and 1850, starvation and forced emigration resulted in at least a quarter of Ireland’s population lost (~1 million dead and 1-2 million emigrated). 1847 was the single most devastating year of the Famine. Irish President Mary Robinson dedicated the monument, which was the first in the United States to memorialize the Great Hunger. Robinson was a Harvard Master’s graduate who was about to leave the Presidency and become the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Created by well-known Irish sculptor Maurice Harron, the sculpture shows a mother holding her dead child while reaching out to her older son, who is leaving with his sister in search of survival in America.

The Memorial Committee’s idea at first faced some opposition from members of the Cambridge Historical Commission over concerns about whether the subject and design of the memorial would fundamentally change the character of the Common. However, the memorial had the support of significant figures like Senator Ted Kennedy, Governor Bill Weld, and Cambridge Mayor Sheila Russell. Supporters stressed the importance of the United States’ openness to immigration and the injustice of starvation in a world with plenty of food which the memorial represents. Despite some concerns about changing the character of the Common, the Historical Commission’s final vote was unanimous in support of the memorial.

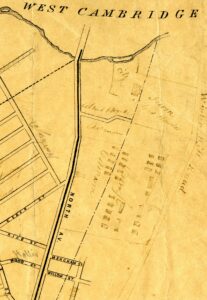

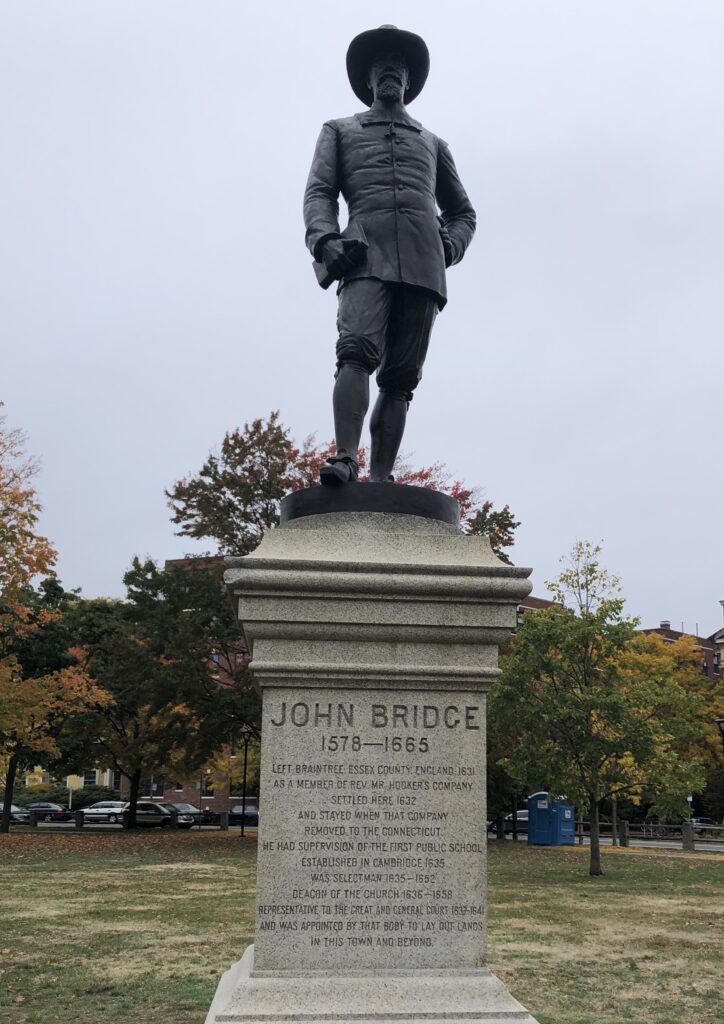

John Bridge Statue (Cambridge Common)

Nicknamed “The Puritan,” this statue was given to the city of Cambridge by Samuel Bridge in 1882 in honor of his ancestor, John Bridge. The inscriptions on the base of the statue read as follows:

- John Bridge • 1578–1665 • Left Braintree, Essex County, England, 1631, as a member of Rev. Mr. Hooker’s company • Settled here, 1632, and stayed when that company removed to Connecticut • He had supervision of the first public school established in Cambridge, 1635 • Was selectman, 1635–1652 • Deacon of the church, 1636–1658 • Representative to the great and general court 1637–1641 • And was appointed by that body to lay out lands in this town and beyond.

- This Puritan helped to establish here church school and representative government and thus to plant a Christian commonwealth.

- Erected and given to the city, September 20, 1882, by Samuel James Bridge, of the sixth generation from John Bridge.

- “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength.”

This statue is a prime example of the Colonial Revival movement. Many historians trace the origins of this movement to the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1876. This ushered in a wave of nostalgia beginning in the late 19th century. Many white Americans were also responding to the major changes they saw happening in American culture and society, especially increasing urbanization and industrialization, stratification of wealth, and immigration from areas other than Northwest Europe. This led to a fascination with all things colonial – often not accurate, but rather an idealized version of what early America was like. The image of John Bridge that the statue creates certainly fits this mold: Bridge’s confident posture – leg forward as if he is “claiming” the new land – is bolstered by his carrying of a Bible, a detail which lends credibility and even divine right to his and other early colonists’ occupation of the land.

Prince Hall Memorial (Cambridge Common)

Dedicated in 2010, this monument honors the founder of the first Black Masonic lodge. Born c. 1735-38, Hall was born into slavery but was emancipated as a young man and became a leader in the free Black community in Boston. He was an abolitionist and a proponent of black public education. Hall worked in Boston as a peddler, caterer and leatherworker, eventually owning his own leather shop. We know that Hall was a homeowner who voted and paid taxes. We have likely evidence that Hall served in the militia during the Revolutionary War, and he was a vocal supporter of Blacks serving in the military, arguing that it would help their arguments for freedom after the war. Prince Hall worked with others to propose legislation for equal rights. He also hosted community events, such as educational forums and theatre events to improve the lives of Black people in Boston.

Prior to the American Revolutionary War, Prince Hall and fourteen other free Black men petitioned for admission to the all-white Boston St. John’s Lodge, but they were turned down. Hall and 15 other African Americans then sought and gained admission into the Grand Lodge of Ireland in 1775. The Lodge was attached to the British forces stationed in Boston. Hall and other freedmen founded African Lodge No. 1 and he was named Grand Master, but the Black Masons had limited power; they could meet as a lodge, take part in the Masonic processions, and bury their dead with Masonic rites but could not confer Masonic degrees or perform any other essential functions of a fully operating Lodge. Unable to create a charter, they applied to the Grand Lodge of England. The grand master of the Mother Grand Lodge of England, issued a charter for the African Lodge No. 1 in 1784 – the new country’s first African Masonic lodge.

The monument consists of five standing slabs containing selections of Hall’s writings and speeches, along with his signature in his handwriting and the words of other abolitionists. The monument does not contain an image of Hall because none is known to exist for certain. Visitors may wonder about the shape of the stones in a near-circle. What is the purpose? To pull the viewer in and create a feeling of intimacy? To underscore the “hemmed-in” nature of Black existence in early America? We cannot know for certain, but these are all possible explanations.

The Cambridge City Council established the Prince Hall Memorial Committee to organize the monument in September 2005, and spent the next five years designing the structure, educating students and donors, and raising the necessary $100,000 to install the monument. In an October 2008 resolution, the City Council first voted to name Hall a founding father, someone who “challenged the principles of democracy, civil rights, and equality—those who embody the ‘we’ in ‘we the people.’” The resolution cited his efforts to integrate the Revolutionary Army, establish a school by and for Black citizens, and petition to end slavery and the slave trade as worthy of permanent recognition.

Sean Collier Memorial (MIT Campus)

Sean Collier was a 27-year-old MIT campus police officer in 2013, when he was killed in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing when the suspects attempted to steal his service weapon. The memorial was dedicated in 2015, two years after Collier’s death, after extensive consultation with a monument committee made up of MIT faculty, students and police officers.

The design consists of granite blocks arranged in five “wings” that form arched shapes; from above the memorial looks like the outstretched fingers of a hand (MIT’s motto is “Mens et Manus” – Mind and Hand). The granite symbolizes Collier’s love of hiking in the White Mountains of NH with the MIT Outing Club. The memorial is situated immediately next to the location where Sean Collier was murdered. An opening in the structure frames a view of the spot where he was sitting in his MIT Police car responding to a call for help, when he was ambushed and shot. Raised stainless steel buttons encoding Collier’s police badge number “179” in Braille are installed into the pavement beneath the memorial arches, to discourage its abuse by skateboarders. Smaller granite blocks are placed around the periphery of the memorial, to provide seating for visitors. At night, in-ground LEDs illuminate the structure, and also represent the configuration of the stars overhead on the fatal night of April 18, 2013.

The Hiker Statue (Arsenal Square)

Designed by Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson, the statue was originally created for the University of Minnesota in 1906 to commemorate the students who served in the Spanish-American War. At least 50 copies of the statue were made and placed around the United States, with the Cambridge copy dedicated in 1947. The figure is called “The Hiker” because of the long hikes soldiers in these conflicts had to endure through the countryside. The placard on the monument states:

“This Monument Erected by the city of Cambridge to her sons who on land and sea defended the nation’s honor in the war with Spain, the insurrection in the Philippines, and the China Relief Expedition 1898 – 1902. Dedicated October 12, 1947 under the auspices of Leslie F. Hunting Camp No. 12 United Spanish War Veterans.”

The Spanish-American War began in 1898 with the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, which led to the United States intervening in Cuba’s war for independence from Spain. The Treaty of Paris that ended the war gave the U.S. temporary control over Cuba and ownership of the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. The U.S.-Spain battle was waged in the Philippines as well.

The monument is also dedicated to those who fought in the Boxer Rebellion. From 1899-1901, China attempted to oust foreign and Christian influences from its land. In response to reports of an invasion by the Eight Nation Alliance of American, Austro-Hungarian, British, French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Russian troops to lift the siege, the initially hesitant Empress Dowager Cixi supported the Boxers and declared war on the foreign powers. The Eight-Nation Alliance brought 20,000 armed troops to China, defeated the Imperial Army, and arrived at Peking on August 14, 1901, relieving the siege of the Legations. Uncontrolled plunder of the capital and the surrounding countryside ensued, along with summary execution of those suspected of being Boxers. The resulting Boxer Protocol provided for the execution of government officials who had supported the Boxers, provisions for foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and 450 million taels of silver—approximately $10 billion at 2018 silver prices and more than the government’s annual tax revenue—to be paid as indemnity over the course of the next 39 years to the eight nations involved, including the United States.

The form of the soldier in this monument – strong, confident, masculine – reflects the ideal of the rugged outdoorsman championed by Theodore Roosevelt and others during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was especially important in response to the urbanization and industrialization of the country in the late 19th century, which led to a call for men to be more physical, tough and outdoorsy. This model leads to questions about the representation of American masculinity and triumphalism in juxtaposition to the European, Caribbean and Asian men they were fighting in these conflicts, with the physical form of the soldier himself serving as a display of U.S. imperial force and superiority.

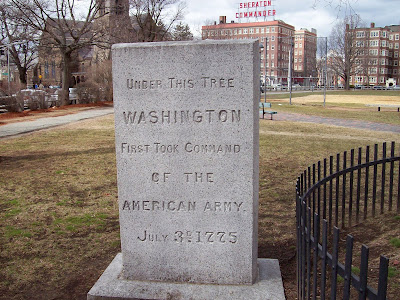

Site of the Washington Elm (Cambridge Common)

The Washington Elm sprouted c. 1713 and lived about 210 years before dying of disease and being removed in 1923. Located on the Cambridge Common, the elm gained notoriety in the 1830s when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote that, “under this tree Washington first took command of the American Army, July 3, 1775.” In 1876, the “discovery” and publication of a fictional work called “The Diary of Dorothy Dudley” contained an entry dated July 3, 1775, that claimed to be a firsthand account of Washington taking command of the army beneath the elm tree, further entrenching the legend. The date of July 3, 1775, is accurate, but there is no contemporary record of this event taking place under the Washington Elm (although it may well have taken place on the Cambridge Common).

An excerpt from “The Washington Elm Tradition” by Samuel Francis Batchelder (Cambridge Historical Society Proceedings, 1925) describes what was done with the wood from the Washington Elm after it was taken down:

“The remains of the famous relic were rescued with some difficulty from a horde of souvenir hunters and taken in charge by the city government. It was determined to make of them “an object lesson in patriotism for the whole country.” To this end they were sawn into numerous fragments. A large piece of the main trunk was sent to the governor of each of the forty-eight states, and the section from which the rings were counted was polished and presented to the museum at Mt. Vernon. From the smaller branches were made a quantity of gavels, two of which were presented to the legislative bodies of each state and many to fraternal organizations, etc. One hundred and fifty small blocks of the wood were given to local applicants, thirty-two to various counties, and two hundred and fifty were sent out over the country. In all about one thousand pieces were distributed, each suitably labeled with a metal plaque.”

Although the elm was removed in 1925, the stone remains to indicate where it stood. The Elm is a symbol of patriotism, and bears a place of honor on the seal of the city of Cambridge.

Bigelow Sphinx (Mount Auburn Cemetery)

Designed by Dr. Jacob Bigelow and sculpted by Martin Milmore, the Sphinx was unveiled in 1872. The monument is notable in that Bigelow designed and paid for it by himself, in contrast to the vast majority of Civil War memorials in both the North and the South, which were decided on and financed by committees. Bigelow had originally proposed this committee model to the trustees of Mt. Auburn, who accepted it, but the process soon ran out of steam and Bigelow decided to continue the memorial process on his own. There is very little text on the Sphinx, and its unique symbolism ensured that its meaning was not self-evident, either to future generations or even to audiences in its own time. Bigelow had to contextualize it for viewers, and after he died its meaning changed. It was intended as a memorial to the Union soldiers who fought and died in the Civil War, but used the unusual image of the sphinx instead of a more traditional soldier, obelisk, etc. Bigelow was one of the early designers of Mt. Auburn and incorporated a number of Egyptian motifs into his designs.

Bigelow wrote that he chose the figure of the sphinx because it represented “repose, strength, beauty and duration,” qualities of the nation at peace. Bigelow’s choice of a female sphinx was unusual, as most Egyptian sphinxes were male. This may have allowed the sphinx to take on the allegorical forms of ideas such as liberty, hope or victory, or the traditionally female figure of America herself (represented in the next decade by the Statue of Liberty).

The figure of the sphinx embodies a combination of Euro-American and African-American attributes, resulting in a complicated statement about what the newly-reunited America would look like. The head is that of a Euro-American woman, wearing an Egyptian headdress but with an American eagle on it rather than an Egyptian asp. She also wears around her neck an American military medal shaped like a six-pointed star. The pedestal has an Egyptian lotus carved on one end and an American water lily on the other. The “Africanness” of the body – lion, animalistic, wild – is dominated by the “Angloness” of the head – intelligent, civilized. Bigelow was anti-slavery, but he was not an integrationist, and his design alludes to the idea that, while slavery was ended by the war, racial equality was not to be the new ideal. Black would always be subordinate to white, and only in keeping this order in place would America remain at peace. The physicality of the lion’s body also represents the idea that Black labor would continue to be the “muscle” behind the nation’s economy, even without slavery.