Helen Lee Franklin

We recently learned about a fascinating story-map series, Stories of the Great Migration, on the National Parks of Boston’s website. Boston served as one of the many destinations for African American southern migrants searching for new economic opportunities and fleeing discrimination during the Great Migration. One of the articles in the National Parks of Boston’s series tells the story of Helen Lee Franklin, a teacher-turned-social justice advocate, who journeyed from the South to the Boston area in the early 1900s and had many ties to Cambridge. The series’ author, Megan Woods, and the National Parks of Boston have kindly allowed us to repost this on the CHS website; you can also view the original story with its map feature here.

Helen Lee Franklin

October 1895 – January 19, 1949

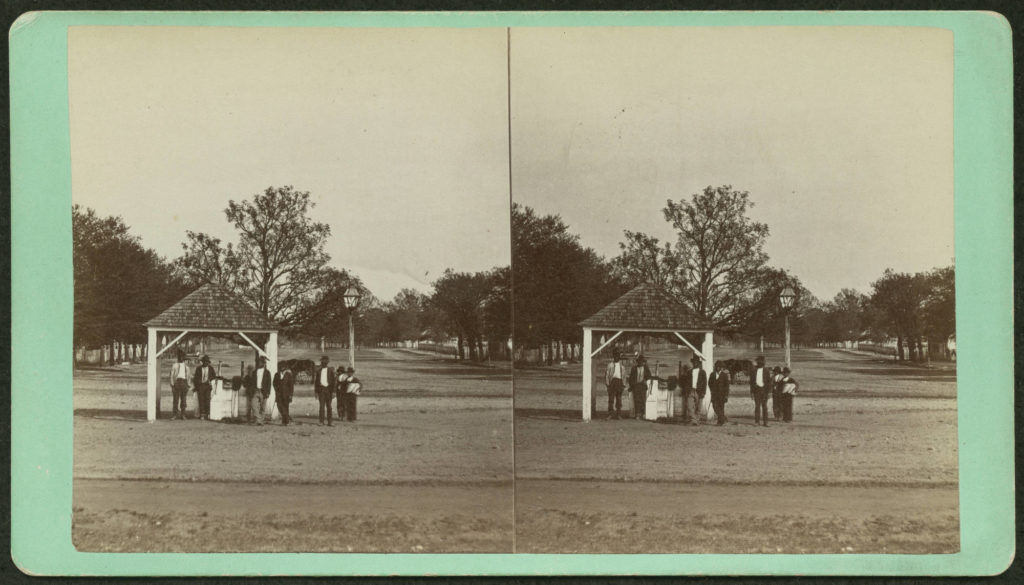

October 1895: Richland Avenue, Aiken, Aiken County, South Carolina

Born in Aiken, South Carolina to Sherman and Henrietta Lee, Helen grew up in this southern town with five of her siblings. While Helen’s mother stayed home to take care of their growing family, her father worked as a printer.

Despite being founded by three black men, Aiken County was plagued by racial tension and violence against African Americans during the 1870s. According to family legend, this continued tension within the county affected Helen’s family: her father was “harassed for printing and distributing literature condemning segregation and discrimination.” This harassment resulted in the family’s move North.[1]

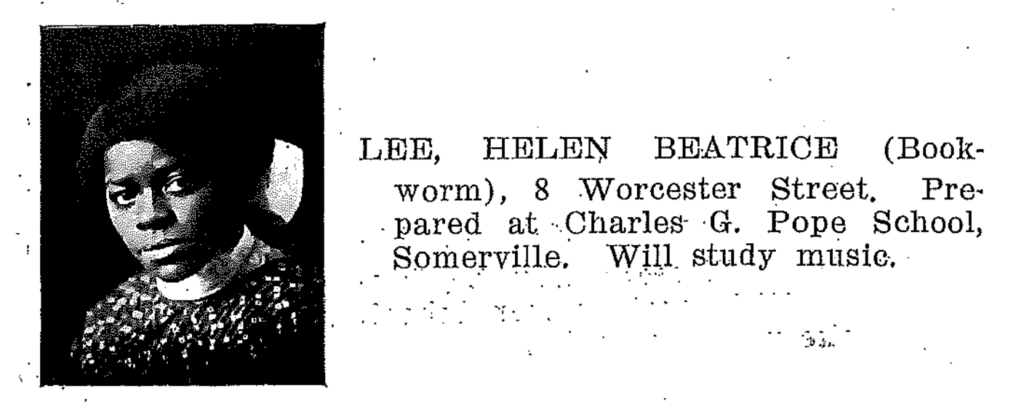

1914: 8 Worcester Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts

In the early 1900s, Helen and her family settled in Massachusetts. First they lived in Somerville, where Helen attended Charles G. Pope School. Her father worked as a real estate agent and her mother worked as a dressmaker. They later joined the small, active black community in Cambridge, living on Worcester Street and then Western Avenue. Helen attended Cambridge High and Latin School, graduating in 1914. Her yearbook photo from this year identified her as a “Bookworm” who studied music.[2]

1920: Palmer Memorial Institute, Sedalia, North Carolina

A few years after graduating from high school, Helen moved to the South to work at the Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, North Carolina. Principal Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown founded this Institute to teach African American children in the rural South. She shared a similar background to Helen, having moved to Cambridge from North Carolina as a young girl. Dr. Brown frequently traveled between Sedalia and Cambridge to fundraise for her school. During one of these trips, Helen Lee and Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown’s paths may have crossed.

While we do not know when Helen Lee first began working at Palmer Memorial Institute, Ambassador Harriet Lee Elam-Thomas, Helen’s niece, recalled that her mother Blanche did not wait for her sister Helen to return home from working at the Palmer Institute before marrying Robert Elam in the spring of 1920.[3]

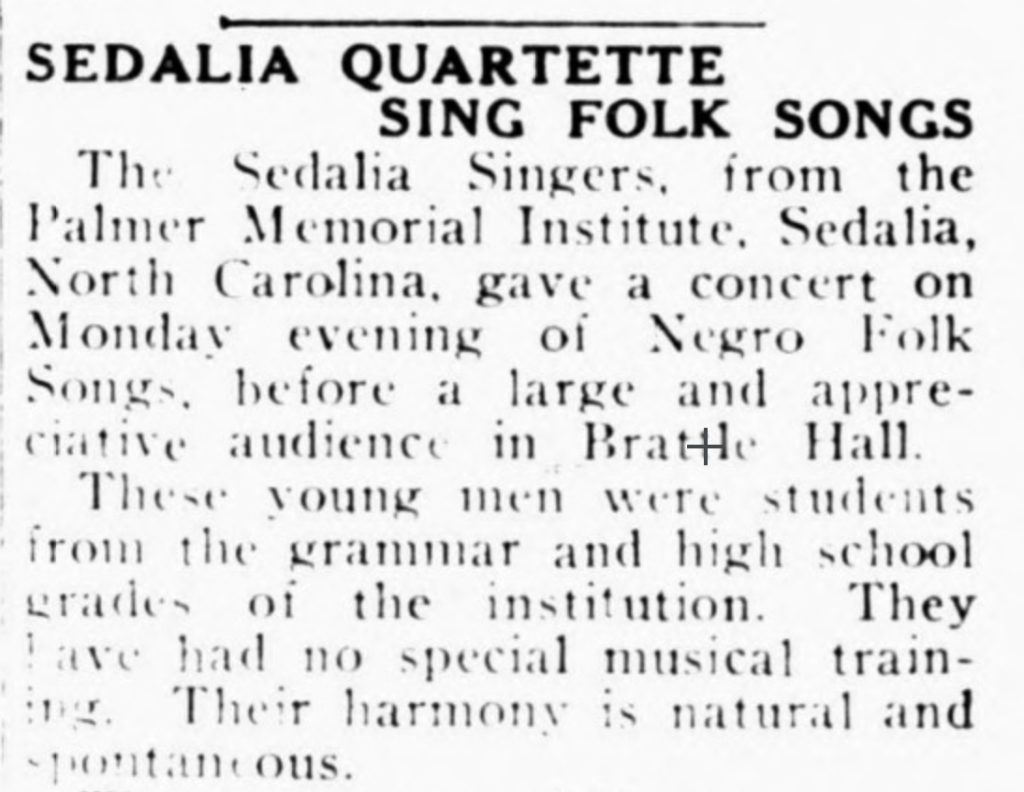

1924: Brattle Hall, Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Throughout the 1920s, Helen demonstrated her love for education by continuing to work at schools for African Americans in the South. She may have briefly worked at the Utica Normal and Industrial School in Utica, Mississippi in addition to serving as a secretary at the Palmer Institute for several years. In March 1924, Helen traveled back to Cambridge with the “Sedalia Quartette,” a group of singers that performed in the North to help raise money for the Institute. At one of these performances held at Brattle Hall in Cambridge, Helen participated by performing “One Day at Palmer.”[4]

1929: Cambridge Community Center, Howard Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts

On August 10, 1929, the Cambridge Community Center opened its doors with Helen Lee as its first secretary. Helen had been instrumental in establishing this community center; she hosted one of the initial planning meetings for the community center as well as chaired a committee that sponsored a benefit to raise funds for it. Over the next few years, possibly until 1936, Helen continued working at the Community Center or supporting its programs and events.[5]

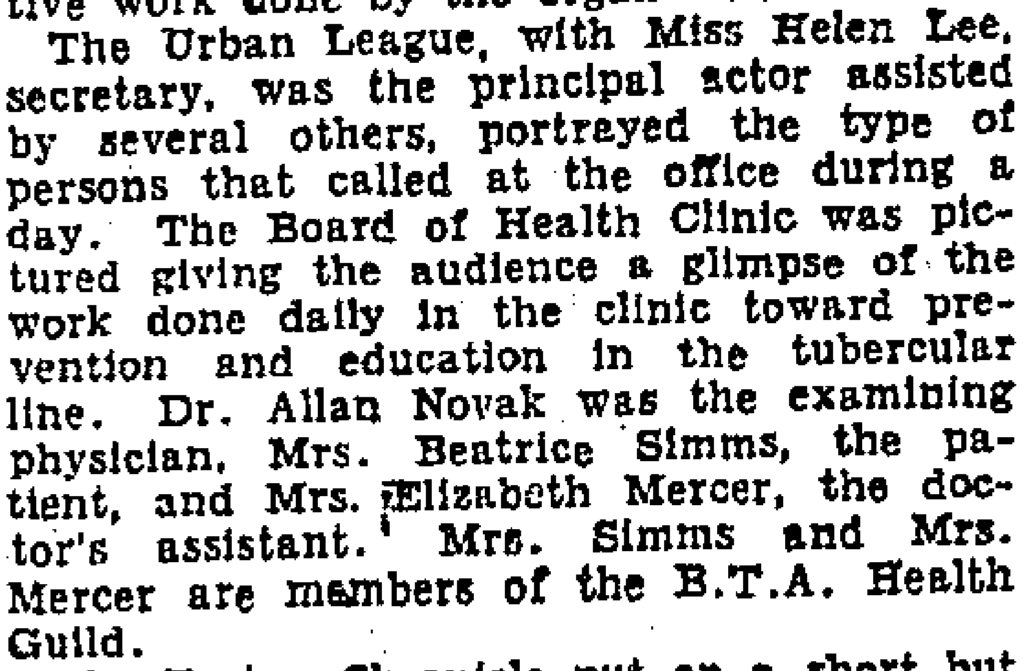

1931: Boston Urban League address, Camden Street, Boston, Massachusetts

By 1931, Helen had begun devoting her attention to another local organization, the Boston Urban League. Established in 1919, the Boston Urban League dedicated itself to helping African Americans faced with economic, social, and health issues, specifically focusing on employment and housing. From 1931 to about 1936, Helen served as assistant secretary of the Boston Urban League under the leadership of executive secretary George Goodwin. Newspapers frequently mentioned her involvement at health fairs to educate the public about the League. For example, one of these programs involved discussing the variety of people who come to the Boston Urban League for assistance.[6]

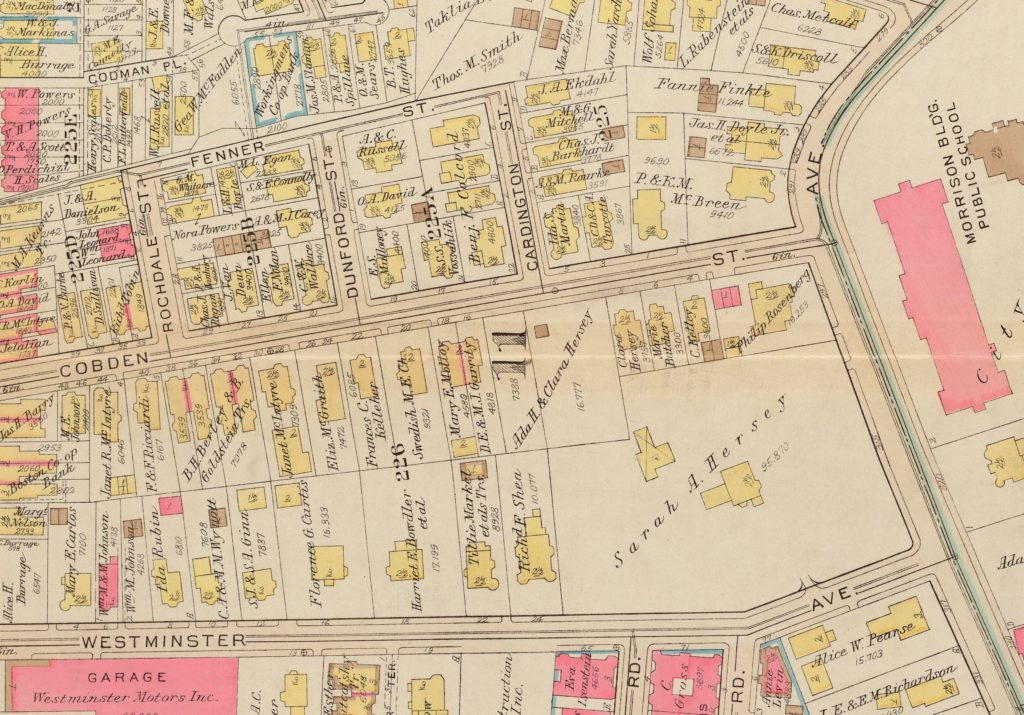

1935: 1 Cobden Street, Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts

Around 1935, Helen moved from Cambridge to Roxbury. Following her father’s death in December 1930 and her mother’s death in January 1931, Helen spent the early 1930s trying to keep her family home at 194 Western Avenue in Cambridge. Notices in local papers demonstrated Helen’s efforts to pay off her family’s debts and owed taxes. Despite her persistence, this hardship likely led to her decision to move to Roxbury, another neighborhood with a strong black community. By 1935, she lived as a lodger at this address in Roxbury with other lodgers who were also migrants from the South and the West Indies.[7]

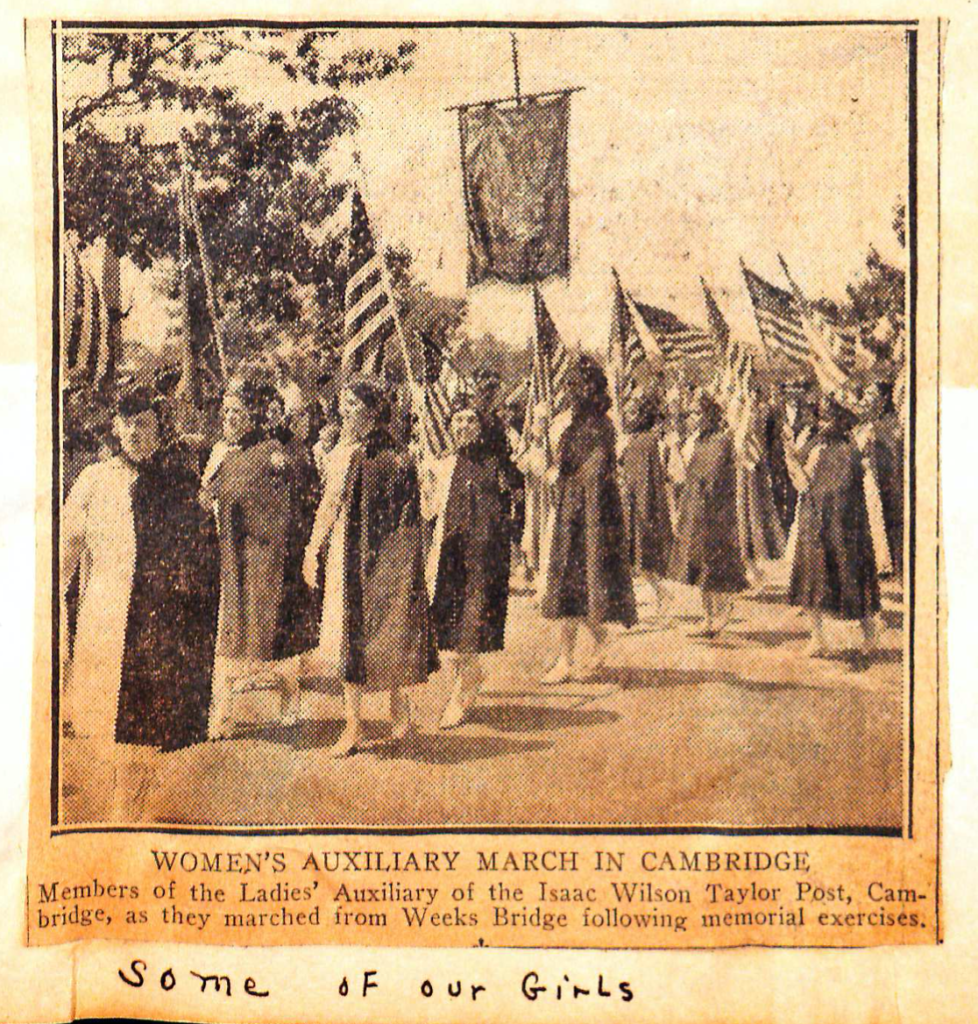

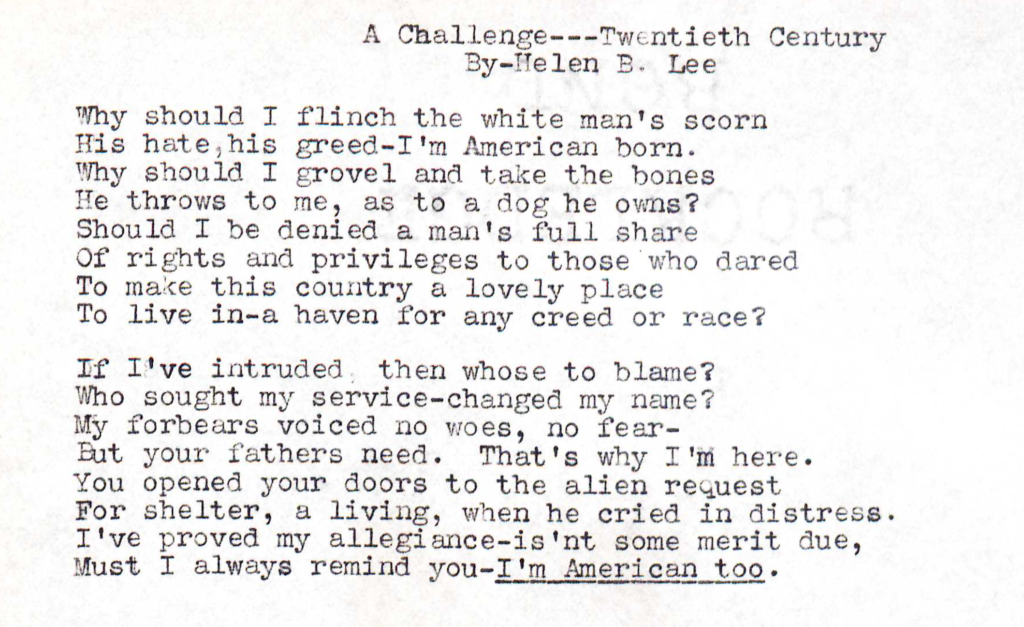

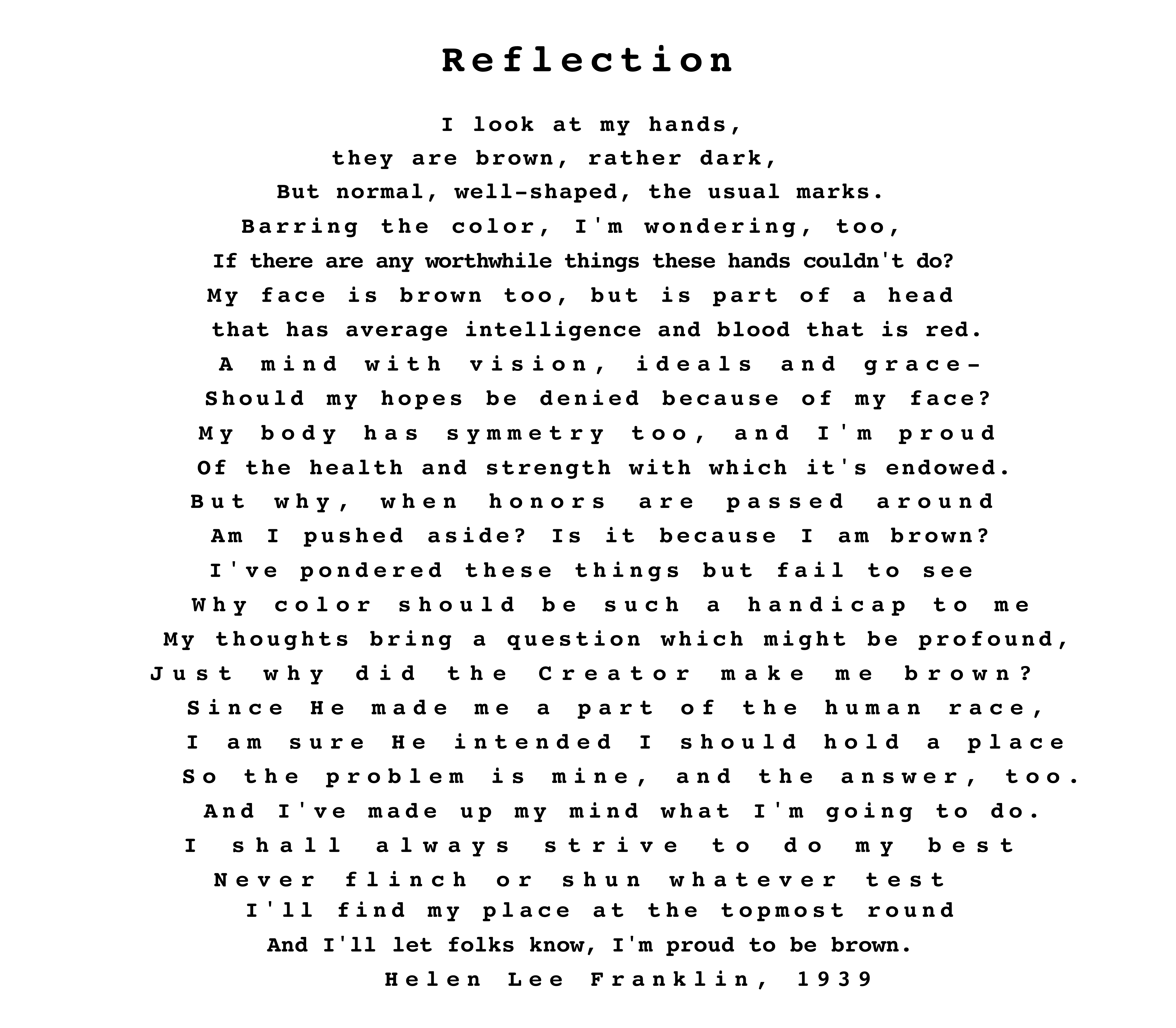

October 1939: Inman Square fire house, Cambridge, Massachusetts

At a “Musical and Tea” held at the Inman Square Firehouse, Helen’s niece, Annetta, read two poems written by Helen for an event sponsored by the Ladies Auxiliary of the Isaac Wilson Taylor Post, No. 2443, Veterans of Foreign Wars. In addition to the Boston Urban League and the Cambridge Community Center, Helen Lee devoted herself to several other clubs in the 1930s, including this Ladies Auxiliary post. Similar to other auxiliary posts of Veterans of Foreign Wars, this post supported veterans and their families through a variety of events, from participating in parades to hosting social gatherings.[8]

From 1934-1936, Helen served as the Post’s “Musician” and helped organize club events along with her sister, Blanche, who also served in leadership positions. The poems Helen wrote for this event demonstrate her awareness of injustice and discrimination towards African Americans and her desire to bring attention to and take action on these issues.[9]

1941: Charlestown Navy Yard, Charlestown, Boston, Massachusetts

In November 1941 Helen Lee began working at the Charlestown Navy Yard as a typist. Her motivations for working at the Navy Yard are unclear, although her relatives’ dedication to service may have influenced this decision: two of her brothers served in World War I. Her sister’s three sons later served in the Army during World War II.[10]

November 1943: Charlestown Navy Yard, Charlestown, Boston, Massachusetts

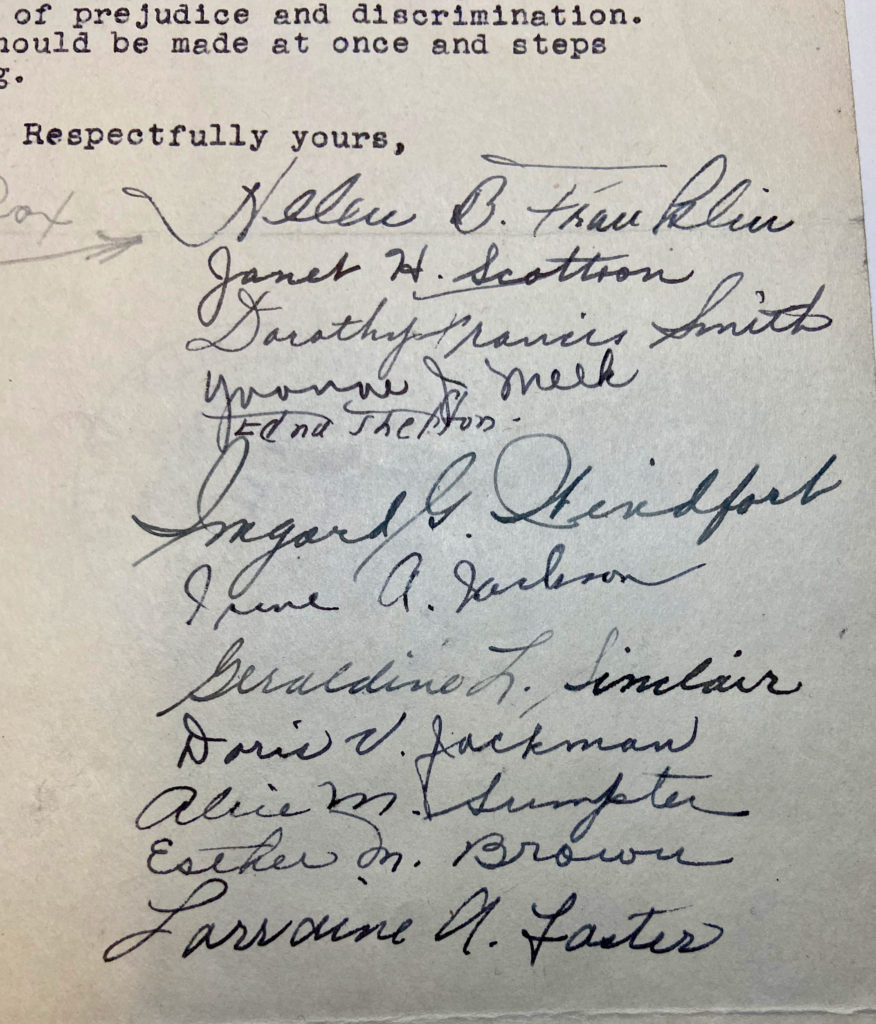

With her involvement in different community and activist organizations, it is no surprise Helen stood up for herself when she believed her Charlestown Navy Yard supervisors discriminated against her and her colleagues.

On November 6, 1943, Helen Franklin (the previous month she married her husband, Clarence Franklin), and eleven other women sent a letter to the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) regarding discrimination in their typist training section at the Navy Yard. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the FEPC to investigate discrimination in the defense industry, and these women saw this commission as their avenue to achieve justice. Helen and these women wrote in their letter that they believed their supervisors were making their section a “Jim Crow” section and that supervisors gave white women promotions before them.[11]

Not wanting to leave this investigation solely in the hands of the FEPC, Helen Franklin also contacted Julian D. Steele, President of the Boston Branch of the NAACP. Julian Steele responded to her letter, noting, “I am looking into the matter of Jim Crow at the Navy Yard… I feel that something vigorous should be done to halt this practice.” He planned to reach out to other federal and local organizations, such as Boston Urban League, to investigate this discrimination further.[12]

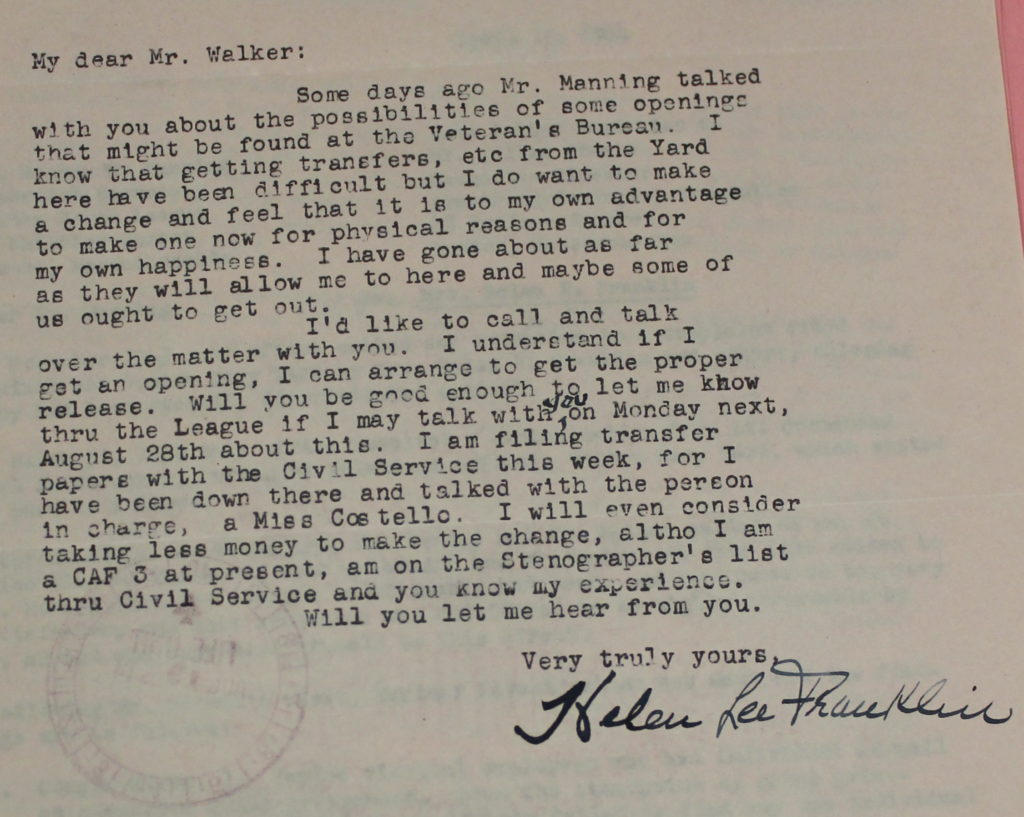

April 1944: War Manpower Commission, Tremont Street, Boston, Massachusetts

Ultimately, the Fair Employment Practices Committee dismissed this case “due to merits,” meaning the claim did not have substantial evidence to support it. Nevertheless, Helen did bring awareness to discrimination at the Navy Yard. While looking into her case, investigators recognized at least seven other alleged cases of discrimination at the Navy Yard. Although the Navy Yard’s investigation denied all accusations, federal investigators noted that discrimination did exist at the yard, yet stated “we cannot prove it.”

After this outcome, Helen Franklin reached out to the War Manpower Commission, a commission created to manage wartime labor needs, requesting a transfer to the Veteran’s Bureau. She wrote, “I know that getting transfers, etc from the Yard here have been difficult but I do want to make a change and feel that it is to my own advantage to make one now for physical reasons and for my own happiness. I have gone about as far as they will allow me to here and maybe some of us ought to get out.”[13]

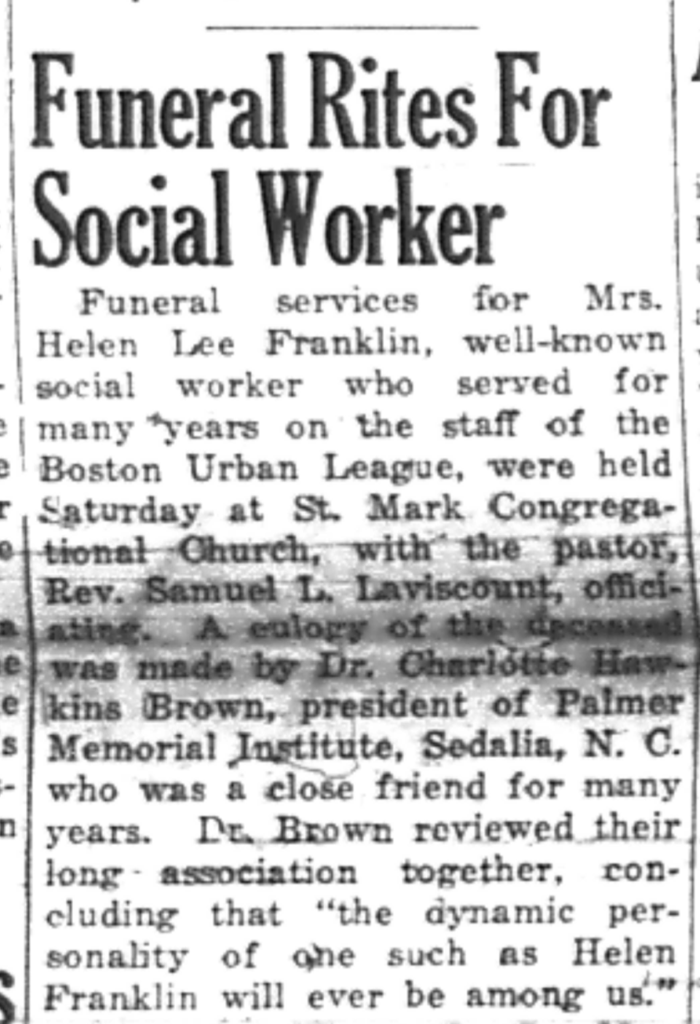

January 1949: St. Mark Congregational Church, Townsend Street, Dorchester, Massachusetts

Helen Beatrice Lee Franklin died January 19, 1949. Over the last few years of her life, Helen remained active working with veterans at the Veterans Rehabilitation Center of Boston, as well as served on the Executive Board of the Boston Branch of the NAACP in 1946. Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown, president of the Palmer Memorial Institute and life-long friend, delivered the eulogy at Helen’s funeral held at St. Mark Congregational Church. Dr. Brown remembered, “the dynamic personality of one such as Helen Franklin will ever be among us.” Helen’s obituary praised her for being a “self-sacrificing and public-spirited leader.”[14]

Legacy

Tracing Helen’s story demonstrates a life dedicated to the community and standing against injustice, whether in the South or in and around Boston. Her legacy continues through the lives of her nephews, nieces, and their children, one of whom recalled, “Aunt Helen gave all of her nieces and nephews great encouragement and support, pushing all of us to get a good education.” Among these relatives would be the first black Chief Justice of the Boston Municipal Court, a U.S. Ambassador, a President of a college, as well as other careers and paths that serve their communities.[15]

FOOTNOTES

[1] Harriet Lee Elam-Thomas with Jim Robison, Diversifying Diplomacy: My Journey From Roxbury to Dakar (Nebraska: Potomac Books, 2017), 19.; Walter Edgar, ed., The South Carolina Encyclopedia Guide to the Counties of South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), ProQuest Ebook Central, 8-9.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1900, Aiken, Aiken, South Carolina, Enumeration District 0022, page 10.

According to Harriet Lee Elam-Thomas, Helen Lee and her family’s relative was Samuel J. Lee, one of the three founders of Aiken County. (Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 19).

Image: Palmer, James A. “No. 64, Richland Avenue, recto.” Stereograph. Chibbaro Stereograph Collection: 186u-1997. South Caroliniana Library. University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

[2] United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1910, Somerville Ward 2, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Enumeration District 0992, Roll T624_604, page 12B.; Cambridge High and Latin School, Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook, Cambridge, 1914.

Image: Cambridge High and Latin School. Cambridge High and Latin School Yearbook. Cambridge, 1914.

[3] “Dr. Charlotte Hawkins Brown,” North Carolina Historic Sites, February 2020, https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/charlotte-hawkins-brown-museum/history/dr-charlotte-hawkins-brown.; Ambassador Harriet L. Elam-Thomas, interviewed by James T. L. Dandridge, II, June 2, 2006, oral history, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project. https://adst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Elam-Thomas-Harriet-L.pdf.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1920, Cambridge Ward 4, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Enumeration District 47, Roll T625_708, page 6B.

Image: Commencement activity outside of Stone Hall, Palmer Memorial Institute. Charlotte Hawkins Brown Papers. Folder: Photographs: Students, events, buildings, n.d. Sedalia Public School, 1938-39, n.d. HOLLIS collection level record 000605309 . RLG collection level record MHVW85-A64. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. https://images.hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=HVD_VIAolvwork20013559&context=L&vid=HVD_IMAGES&search_scope=default_scope&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US

[4] “Sedalia Quartette Sing Folk Songs,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Mar. 15, 1924, pg. 7, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19240315-01.2.64&srpos=2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-sedalia+quartette——. “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” Boston Chronoicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, pg. 1.

Image: “Sedalia Quartette Sing Folk Songs,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Mar. 15, 1924, pg. 7, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19240315-01.2.64&srpos=2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-sedalia+quartette——.

[5] Odile Sweeney, “Community Center Plans New Building in 1947,” Cambridge Chronicle (Cambridge, MA), 1946, pg. 39.; “Benefits Cambridge Community Centre,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA),May 18, 1929, pg. 1, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19290518-01.2.5&srpos=11&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22helen+lee%22—– ; “New Community Centre Opened Tuesday Night,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Aug. 10, 1929, pg. 2, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19290810-01.2.14&srpos=12&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22helen+lee%22—— ; “Staff Meeting At Community Center” Cambridge Chronicle and Cambridge Sun (Cambridge, MA), Apr. 2, 1936, pg. 9. ; “Community Center has its first Demonstration,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Oct. 24, 1931, pg. 1, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19311024-01.2.7&srpos=4&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22—— ; C. Elliot Freeman Jr., “Boston News,” The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967) (Chicago, IL), May 6, 1933, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender. pg. 20.

Image: Cambridge Community Center, http://www.cambridgecc.org/photo-archive.html.

[6] “Boston,” Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Apr. 25, 1931, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, pg. 18. “Our Milestone,” Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts, accessed January, 2020, https://www.ulem.org/centennial; Robert C. Hayden, “A Historical Overview of Poverty among Blacks in Boston, 1850-1990.” Trotter Review 17, no. 1 (September 2007), 137, https://archive.org/details/trotterreview171willi/page/136/mode/2up.

Image: “Boston,” Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Apr. 25, 1931, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, pg. 18

[7] “Commonwealth of Massachusetts Probate Court,” Cambridge Sentinel (Cambridge, MA), Sept. 26, 1931, pg. 5, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Sentinel19310926-01.2.40.4&srpos=8&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22—— ; “Delinquent Tax Sales Collector’s Notice,” Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, MA), Dec. 8, 1933, pg. 8, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Tribune19331208-01.2.91&srpos=13&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22helen+b.+lee%22——; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1940, Boston, Suolk, Massachusetts; Enumeration District: 15-399, Roll: m-t0627-01669, page 12A; Department of Public Health, Registry of Vital Records and Statistics. Massachusetts Vital Records Index to Deaths [1916–1970]. Volumes 66–145. Facsimile edition. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

Image: G.W. Bromley & Co.. “Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury.” Map. 1931. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center,

https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:1257c411w

[8] Musical and Tea, section of yearly history, 1939, “Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940” (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

Image: “Women’s Auxiliary March in Cambridge,” newspaper clipping, “Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1940-1941” (Folder 9), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

[9] List of Officers, 1934, 1935, 1936 “Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1934-1938” (Folder 7), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

Image: “A Challenge, 1939,” Poem from scrapbook, page with two poems by Helen B. Lee, 1939, “Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940” (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300

[10] Joseph A. Smith, Regional Director, War Manpower Commission, to Lieutenant Commander Paul S. Strecker, Personnel Division, Boston Navy Yard; Fair Employment Practice Committee, December 17, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-1944; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-1946, Box 1; Records of the Committee on Fair Employment Practice 1940-1946, Record Group 228; National Archives at Boston.; Helen Lee to Julian D. Steele, August 9, 1943, Julian D. Steele Collection, NAACP Correspondence 1929-1947, Box 20, Folder 5, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.; Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 20-21.

Image: Boston National Historical Park: Image ID = 9369-2.

[11] 11 other women: Janet H. Scottron, Dorothy Francis Smith, Yvonne J. Meek, Edna Thefton, Imgard G. Windfort, Irena A. Jackson, Geraldine L. Sinclair, Doris V. Jackman, Alice M. Sumpter, Esther M. Brown, Larraine A. Foster.

Helen Franklin et al. to Richard Walker, Fair Employment Practice Committee, November 6, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-44; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-46, Box 1; Records of the Committee on FEP 1940-46, Record Group 228, National Archives.; “Miss Helen Lee, C. Franklin Wed,” Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Oct 16, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, pg. 12.

Image: Helen Franklin et al. to Richard Walker, Fair Employment Practice Committee, November 6, 1943; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-44; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-46, Box 1; Records of the Committee on FEP 1940-46, Record Group 228, National Archives.

[12] Julian D. Steele to Helen Franklin, November 19, 1943, Julian D. Steele Collection, NAACP Correspondence 1936-1944, Box 20, Folder 6, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Image: Department of Defense. Department of the Navy. Naval Photographic Center. (12/1/1959 – ca. 1998). Record Group 80: General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1804 – 1983. National Archives. Local Identifier: 80-G-218855, https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2017/08/10/researching-wwii-navy-ships/

[13] Final Disposition Report, April 12, 1944; Boston Navy Yard, 1-GR-55, 1943-1944; Closed Regional Case Records, 1943-1946, Box 1; Records of the Committee on Fair Employment Practice 1940-1946, Record Group 228; National Archives at Boston.; Helen Franklin to Richard Walker, War Manpower Commission, August 15, 1944; War Manpower Commission. Regional Correspondence Files, Region I, Mass. 1943. Box 17:5; War Manpower Commission Central Files 1942-1945, Record Group 211, Series 269, NAID 6278149. National Archives.

Image: Helen Franklin to Richard Walker, War Manpower Commission, August 15, 1944; War Manpower Commission. Regional Correspondence Files, Region I, Mass. 1943. Box 17:5; War Manpower Commission Central Files 1942-1945, Record Group 211, Series 269, NAID 6278149. National Archives.

[14] “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” cropped image, Boston Chronicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, pg. 1.

Image: “Funeral Rites for Social Worker,” cropped image, Boston Chronicle (Boston, MA), Jan. 29, 1949, pg. 1.

[15] Elam-Thomas, Diversifying Diplomacy, 20-21.

Image: NPS/Woods, Based on poem: “Reflection,” Poem from scrapbook, page with two poems by Helen B. Lee, 1939, “Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook: Histories, Reports 1939-1940” (Folder 8), Isaac W. Taylor VFW Post No. 2443 Records, 1932-1999 (131), Box 1, Cambridge Public Library Archives and Special Collections. https://public.archivesspace.dlconsulting.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/9300