The Story of the Bee

Read the full The Story of the Bee by Mary Towle Palmer (1924) as a PDF here

Read the finding aid for The Bee Records, 1861–1934 here

Cambridge Proceedings, Volume 17, 1924

EXTRACTS FROM “THE STORY OF THE BEE”

BY MARY TOWLE PALMER

Since there is no record of the exact pages which Mrs. Palmer read before the Society at its meeting of October 28, 1924, the Editor here reproduces the first three chapters of the book with the gracious consent of Miss Elizabeth Ellery Dana, Mrs. John Allyn, and Miss Elizabeth Harris, three of the original members of The Bee.

CHAPTER I: BEGINNINGS

As people approach the advanced age of three or four score years, they are apt to make the discovery that not far in the future they and their interests will have wholly disappeared from the world unless they can leave behind them some sort of a record which some day some one will like to read. People take to writing autobiographies at seventy, or they begin to write a long-postponed account of some outstanding event in their fast-ebbing lives, with a lingering and loving glance over that precious past which is beginning to grow dim as the years race by and which must be caught and held before it is buried under the accumulating transactions of every day.

And thus it happened with us, the Bee, that one evening half-a-dozen years ago Susanna Willard startled us by asserting that our history must and should be written. At this meeting (the date of which I do not know, for our records are somewhat imperfect) two of our members were elected as historians, and straightway we all glowed over the prospect of renown, the prospect of at least becoming known to a chosen few of our descendants. We were ten years younger as we bade one another good-bye that evening!

The two historians were to be Carrie Parsons, one of the members who had been present at the first meeting of the Bee in 1861, and Susanna Willard, the newest member of the Bee, originator of the plan to write a history.

Five years went by and we heard nothing of the book. It is pathetic to remember that ill-health and manifold cares came upon our historians. After having written a very entertaining paper for our fiftieth anniversary and after having made some valuable memoranda, Carrie Parsons died suddenly two years ago. And last spring Susanna suddenly died.

Their unfinished and much-loved work I hesitatingly pick up. Of those of us who are left, not one feels herself capable of doing justice to a theme so warmly loved, so beautifully alive, so close to our hearts. At this late day I reluctantly yet gladly venture to write about the Bee.

It seems always a miracle in the case of even one individual to be able to look backward over sixty rich years. In the case of an organization the interest is heightened and the color deepened by the variousness of temperament and character that combine to form the unit. For four years the Bee met once a week from November to May, and thereafter for fifty-eight years it has rarely failed to meet every fortnight.

It was once wittily remarked that the Cambridge women seldom marry and never die. This may account for our longevity. I am writing in the year 1923. It was in the fall of 1861 that the first meeting of the Bee was held.

In April, 1861, Fort Sumter had been fired upon. Thus began the four tragic years of fighting between the Northern and Southern States of our Country, the Civil War. In Cambridge there was a passionate fire of patriotism. Her sons went forth to battle. Their little sisters, full of wonder and only half understanding the darkness of the cloud that had come across the sky, were moved to help as their elders were doing. Groups of women of various ages began meeting to sew and knit for the soldiers and to make lint by scraping old linen to be applied to bleeding wounds at the front; a dressing for wounds not tolerated in the present day. There were some detached meetings of workers, during the summer of 1861, and Lizzie Harris records how “one Wednesday in the early summer of that year we petitioned stately Miss Lyman (our school teacher) to omit the usual poetry recitation and let us devote the forenoon to making blue flannel shirts, for which there was imperative demand. She cordially consented, and we worked like beavers in her schoolroom over our self-imposed task, beginning with cheerful chatter, which, as the hours passed, became more and more subdued, backs and fingers wearying with the unaccustomed work. I remember well the triumph with which Sue Whitney waved aloft the first completed shirt. I remember that we bent with renewed and grim vigor over our own garment, to be not far behind her.”

But this was not “The Banks Brigade,” the real Bee. The Bee began its long life on the first day of November, 1861, at the house of Mr. Epes S. Dixwell, on Garden Street. Just a week before this, a group of fifteen (1) girls had been invited to the house of Mrs. Asa Gray, wife of the great botanist, to meet her niece, Julia Bragg, and to sew for the soldiers. Instead of disbanding after this pleasant party, the sixteen agreed to meet on the following Friday at the Dixwell house. It was here that they organized themselves into a working unit and adopted the name of “The Banks Brigade” in honor of General Banks, who at that time led the Massachusetts forces at the front.

At this first meeting Sue Dixwell was elected “Colonel,” because she had knitted for the soldiers more socks than any one else, and of course we must needs give her a military title to express our intimate connection with the army.

From that time until the end of the Civil War the Banks Brigade met every Friday afternoon, choosing that day because of its freedom from study, for we were school-girls of fourteen and fifteen, very busy with our school work as well as with many other affairs.

We met at four at the houses of the members, with supper at six or half-past six. Our mothers presided at the table, but fathers and brothers were, from the beginning, banished to regions unknown.

The suppers consisted often of escalloped oysters, rolls and chocolate, followed by cream pie. Sometimes cream toast was the chief dish, and one cook, amazed at the amount consumed by the young workers, remarked that “those girls ought to have a lot of Harvard students taking supper with them, and then they wouldn’t eat quite so much.”

The plan of admitting Harvard students to the Bee after tea had already been discussed and disposed of, as the following extract from Lizzie Harris will show:

“I remember well how some of the kind elder sisters of the Bee, thinking that life was rather sombre for girls of our age, suggested that our young student friends should be asked to join us after supper on Fridays and have a dance. At a meeting of the Banks Brigade the suggestion was submitted to the Colonel, who turned it down summarily with inimitable scorn. The question was never again raised, and often have I blessed Sue’s quick decision, for she saved the life of the Bee that day.”

After we had sewed diligently through the afternoon, and had enjoyed our supper and our glimpse of the welcome mother in the house, we often allowed the musical Bees to lay aside their sewing and give us tunes. Our blonde Charlotte Dana sang for us with her clear soprano; Katie Toffey, dark-eyed and piquant, plucked her guitar and sang, “Her eyes the glowworm lend thee.” Less romantic was a vigorous tour-de-force on the piano called “Tarn o’Shanter,” wherein the prominent feature was the realistic trotting of Tarn’s horse, followed by a grand crash representing the loss of the horse’s tail. Often Grace Hopkinson cheered us with both piano and song.

During the Civil War, we were never without our knitting, steadily making blue socks with red-and-white borders, knitting while we studied our lessons and while we recited them, knitting while we walked or talked or played.

A Bee record book was started which was to contain a concise account of our doings, but life at fifteen is full of imperative interruptions and writing seems less important than action. This is the only occurrence I find recorded for the eyes of the future, but it is indeed important:

General Order No. 1

Headquarters Banks Brigade

It is ordered that Major-General Banks be elected honorary member of the Banks Brigade.

By Order of Colonel S. DIXWELL.

November 22nd, 1861

Infinitely precious is this little paragraph! It gives the whole spirit of the time in a nutshell. Wherever in our walks we saw a United States flag flying, we saluted it like true soldiers.

We sometimes passed the old arsenal which stood on the corner of Garden and Follen Streets, where a house of singularly beautiful brown stone now stands surrounded by its large garden. There we would stop and peer through the fence to watch the evolutions of the Harvard students who lived there in squads and were armed by the State and were regularly drilled. They formed a guard for the arsenal. Our brothers and cousins were there and might some day become full-fledged soldiers.

As you look along handsome residential Brattle Street, can you imagine that cars drawn by two horses used there to run up and down, their little bells jingling, while the conductor watched for passengers and obligingly stopped wherever he received a signal from a waiting individual? We needed not to hasten to a corner in those days. In 1861 there was plenty of time.

As for the winters, they could quite be depended upon to give us continual snow, so that after the first heavy fall the horse-cars were discontinued, and long vehicles on runners called “barges” took their place and ran every half-hour in and out of Boston, giving the passengers an excellent sleigh-ride.

We paid for our rides with paper currency, for silver disappeared as the war progressed and the little twenty-five-cent bills I remember very well.

The occupants of those old horse-cars were not always more courteous than those in the electric cars of the present day; for once when a member of the Bee entered a car and found it apparently full, a man rose instantly and the lady, supposing that she had been offered a seat, said politely, “Oh, thank you, I don’t object to standing.” The man looked at her astonished and, with startling candor, replied: “I don’t care whether you stand or set. I’m going to get out.”

The following is an extract from Alice Allyn’s reminiscent paper read at our Sixtieth Anniversary:

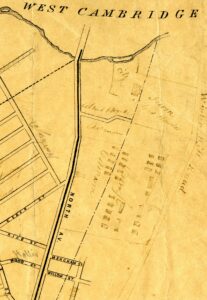

“Sixty years ago! What a different picture Cambridge then presented! Brattle Street, with its tinkling little horse-cars, had the babbling brooks in its gutters in the spring. The lamplighter made his evening round with a ladder. The streets were undrained and rubber boots were a necessity. Harvard Square was a village centre. We collected our mail from a numbered box in the Post Office in the Lyceum Hall building. Under a large tree in the square were the pump and the city scales. The car-horses were watered there from pails which stood on the curbing around the tree.” (There were then no sidewalks, paved or asphalt.)

The members of the Bee, like the rest of womankind, wore hoopskirts, nor could we imagine that a time would ever come when our dresses would be less than six yards around. They are now less than two, and so short as to come not far below the knees. Sitting down in a hoop-skirt was an art that needed to be well practised, otherwise the hoops would flare up in front revealing a ‘limb,” which was something always invisible in those Victorian days. We learned to sit down very carefully, bestowing our skirts behind the calves of our legs, so that we looked as demure as the Puritan maidens we were.

We wore bonnets, real bonnets, tied with a bow under the chin and large enough to hold roses beneath the brim in front. Our dresses frequently were trimmed with velvet of a color called “Magenta” or with touches of a lighter but still purplish tint called “Solferino.” We wore our hair in nets of silk or chenille and later these were decorated with beads. Later still there was a wave of black alpaca dresses, buttoned down the front with large round white buttons.

Every Friday during the four years of the Civil War, the group of young girls sewed diligently, making shirts, night clothes, and even quilts. The record of articles finished at the third meeting reads: 5 pairs hospital drawers, 2 shirts; and at the fifth meeting: 4 pairs hospital drawers, 3 shirts, 1 quilt.

Whoever had been the recorder of the work accomplished became exhausted after this last entry in the little book and no more lists were jotted down, but we know that the work went on with increasing rather than diminishing energy — on and on until, behold! we were growing up, without knowing it! When the war ended, we were actually young ladies of eighteen and nineteen.

One precious bit of print has been preserved, which reads: “From the National Intelligencer

“WASHINGTON, D. C., November 26th, 1862. The ladies of the Samaritan Society of Salem, and those of the Banks Brigade, Cambridge, Massachusetts, are hereby informed that their bounties for the sick soldiers have been duly received and part have already been distributed to grateful recipients.”

Just one week after the birth of the Banks Brigade another organization of the same kind came into existence. It called itself “The McClellan Club,” and was formed of girls somewhat older than the Bees. It also met on Friday evenings at the houses of the members, and the two groups, the Club and the Bee, have always kept a close and neighborly interest in each other. The two often celebrated their anniversaries in common and sent messages to one another. “The McClellan Club” afterwards became “The Lincoln Club,” and at last called itself simply “The Club” and its members became “Clubs.” Its meetings have ceased, but at the time of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Bee, the Club met with us at the Oakley Country Club House and several of its members read most interesting papers.

The paper read that evening by Carrie Parsons is so largely reminiscent of the old days that I give here a quotation from it:

“Through the hot summer of 1861 a group of girls who afterwards went into Club and Bee made ‘havelocks.’ These have-locks were a sort of masculine sun-bonnet and were warranted to prevent sunstroke in the torrid South, and we declared that at least one company of Uncle Sam’s soldiers should be thus protected. So we finished and sent off one hundred havelocks — and heard afterwards that the men used them to clean their rifles. As headgear their whiteness made too good a mark for the enemy.”

Here ends the account of our first four years. We were very young girls. We were “The Banks Brigade.” For four years we had heard echoes of the beating of drums, of distant battles and bloodshed, of lost brothers and cousins and friends, of the fortunes of one General and another, and of the sublime leadership of our President, Abraham Lincoln.

Our meetings had been in the houses of our fathers, presided over by our mothers. It is now long since a mother or father has been left to the Bee, but the remembrance of their benign presence, of their interest in our doings, and of their gentle faces will never fade from our hearts.

CHAPTER II: THE GROWING BEE

The fall of Richmond on the 3d of April, 1865, ended the Civil War, and a long era of peace came to our country. Great was the joy in the Northern States. Flags were flying everywhere. When the news came, all the city houses were illuminated from top to bottom. The world was joyous for twelve days, and then came the overwhelming tragedy of President Lincoln’s death. I was in Washington at that time, and had just escaped being in the theatre on the night he was shot. On the following never-to-be-forgotten Saturday morning, I awoke and heard the bells of Washington tolling, tolling, and I lay and wondered what it could mean. Presently a knock at my door was followed by the shocked face of our old housekeeper, who put her head into the room and solemnly said: “Your President is dead.” At eighteen, I felt a desolating sense of grief at this news. I had met Mr. Lincoln several times during the preceding winter, and had often seen him, with his sad, strange face, at the Capitol or the White House. I felt an adoration for him, and it seemed impossible that life could go on with him out of the world. It was part of the tragedy that he was not permitted to see the ragged armies marching back from the war, marching through Pennsylvania Avenue for two whole days, with their soiled uniforms, their tattered flags and their glory.

In Cambridge remained “The Banks Brigade,” radiant young women of seventeen, eighteen, and nineteen, who had for four years been sewing each week “for the soldiers.” This duty being ended, the society might with propriety disband and hold the remembrance of a finished work.

Certain changes did occur, but its meetings went forward without a break. The name “Banks Brigade” was dropped; the Bee began to meet once a fortnight instead of once a week; and its “Colonel” became its “President.”

Miss Emily Parsons, elder sister of one of our members, had been a nurse in the Northern Army for two years and was later active in establishing what is now the Cambridge Hospital on Mount Auburn Street. Much sewing was needed to furnish the new hospital with bedding, towels, and nightclothes, and the Bee (as it was now called) found plenty of employment for its energetic fingers. Besides this, the Bee had protégés down on the marsh with large and needy families. A certain Mrs. Gribbens was capable of absorbing flannel petticoats and shirts to any extent, and for years our reports of sewing done always contained the name of “Mrs. Gribbens.” Her euphonious appellation lent itself to endless quotation and fun and we were fortunate in having so picturesque an object of charity.

Periodically through our long career we have been attacked by moments of conscience, commanding us to pull ourselves together and behave like other virtuous Clubs. In one such mood we voted to institute a scheme of fines. Under date of 1863 the following inexorable rule is written: “A fine of five cents shall be levied for lateness and a fine of ten cents for absence.” For nine years we tried meekly to follow this law. But in 1872 all fines were abolished forever. For many years our rule has been for each member to pay one dollar at the beginning of the season, and to have no further mention of funds, except when we needed to collect money for sending flowers to some sick member of the Bee, or to a wedding or a funeral.

May blessings fall on Lily Dana for her virtuous Victorian habit of keeping a diary! You will enjoy reading extracts from this priceless document:

“February 7, 1868. Went to the Bee at Mrs. Waterman’s. A Bee was at our house last time. I had to carry the Bee basket there. Stopped for Grace Hopkinson, but she was busy cutting out more sewing for us. Couldn’t wait for her for fear I should be late, and can’t afford to pay any more fines. Had an awful time at the Bee. Grace got hold of some work that I had sewed last time, showed it round to the girls and wondered who it could be that sewed so awfully. I didn’t say anything, except that when she showed it to me I said the stitches were rather huge. Then they asked if it was Miss Rotch’s work, and I said no, she had left early and had sewed button-holes all the time. I shall have to confess at the next Bee.

“February 28. After dinner got ready for the Bee, and was just starting when mother said she should think I would stay at home and see Dick, as he goes back to-morrow, so I took off my things. However, I made mother pay my fine for being late at the Bee. Then I crinkled my hair, put on my pink ribbons, and went to the Bee, which was at Mamie Storer’s. Nothing in particular happened. Katie played and sang a little and we sewed.

“March 13. Went to the Sparks’s, Miss Rotch’s, and Anna Shaw’s to tell them about the Bee, then to Emily Atkinson’s to get the Bee basket, for I have got to have the Bee, as there doesn’t seem to be anybody else to have it. Lugged that great heavy basket way up Quincy Street. Met Mrs. Little, who offered to take home my basket. I was delighted to get rid of it. No one came till five. We had a real nice time. The cook was gone all day, but we got up a supper of coffee and tea, dipped toast, rolls, marmalade and cake.

“March 26. I always hate to leave the Bee, but had to go before dark on account of Mrs. Hubbard’s Wednesday evening Singing Class.

“April 24. Met Anna Page, who went to the Bee with me. She did look lovely in her blue walking-suit and hat. I went down at six o’clock to Mary Fuller’s. We had a real jolly Bee, telling stories all the time about ghosts, robbers, and mediums.

“June 8, 1868. Went to the Bee at Mrs. Waterman’s. Mr. Waterman came to tea and spent the rest of the evening in the parlor with us. We spent most of the time talking about tipping tables and planchette. Grace, Mr. W., and Mary F. tried to tip a table, but didn’t have time before the Bee broke up.

“Nov. 14, Saturday. Charlotte and I went to the Bee as soon as I had finished my dress, which was very late. It was at Mrs. Waterman’s, her last Bee, so she had a nice supper, and in the middle of the table a frosted cake with a wreath of green round it, and stuck all over it little bees and butterflies on wires so that they would vibrate. There was a handsome plain gold ring in it, which Anna Shaw got. We were all quite excited about getting it and I was really in hopes I should, though I already have the ring of the first Bee cake (Sue Dixwell’s).”

Lizzie Harris speaks as follows about some fluctuations in the life of the Bee:

“It was Caroline Parson’s fidelity which held the Bee together during one critical period, and in this she had a devoted and able aid in Grace Hopkinson. Some members had married and left Cambridge, two were invalided, and unable to attend the meetings; others immersed in home cares had become somewhat careless of Bee claims upon time and attention. But Caroline, seconded by Grace, never relinquished her protection. Carefully did she watch over the remnant, holding it together, and finally being instrumental in adding a few members to fill the temporary lack. The critical time passed and never again has the Bee languished.”

A new phase of existence was now beginning, for many of the Bees were growing into beautiful women. Engagements and marriages were events to which we were becoming accustomed, while still there was wonder in our eyes as we saw our members stolen away into a region of romance of which as yet some of us were only dreaming.

I remember my awakening thrill when I first saw Mabel Lowell dressed in a low-cut gown of heliotrope satin, an amethyst necklace resting on her white neck, while her eyes shone like stars. She was like a sumptuous moth emerging from its chrysalis.

Our first wedding was that of Lucy Nichols and Captain White, a handsome young officer of the Northern Army, just after the war was over. To her came the first baby into the Bee, a little girl who never lost her interest for us, and to whom we sent a present at the time of her own marriage.

Then came the marriage (2) of Mollie Buttrick to Frank Goodwin, which took her unfortunately away from Cambridge, and the marriage of Helen Allyn to a charming Norwegian whom she met abroad.

As each Bee married, we gave her a gold thimble, engraved with the letters “B. B.” These were always heavy and handsome and were much prized. Our first badges long ago were made of gutta-percha, with a small silver plate engraved “B. B.” attached. These were sometimes worn with a necklace. After this we wore little bees made of silver, and finally the sixteen original Bees, always carefully and honorably distinguished from the rest of us, wore lovely bees of gold, with ruby eyes, the present of Anna Allyn.

The Bee basket, which was so faithfully carried by Lily Dana from one house to another and which she found rather an irksome load, could hardly have been as large as the dear old Bee basket which, from time immemorial, we have been using, and which is now carried by automobile. It is a large market basket, which once had an iron bar across the top to keep its contents secure, but which for years has been elaborately tied up with yards of twine to keep it firm in the hands of the expressman or the chauffeur. The basket is a species of presiding genius or mascot, like the ark of the Israelites. It always stands on the floor ready to serve the Bees with fresh sewing, holding in its inner recesses the Bee photograph album, and on top of this boxes of spools, tape, needles; holding also the necklace of tortoise-shell with a locket in the shape of a bee, which Mary Cobb brought from Rome, and the long necklace of beads, also from Rome, with its many bees wrought into the bead-work, brought home by Lily Hoppin. Dear old basket! How many merry meetings has it presided over, during its long existence!

In 1877 occurred an event which not only affected one member of the Bee, but really also the Bee itself. Grace Hopkinson took a prominent part one evening in a play given by the Cambridge Dramatic Club. President Eliot of Harvard College sat enchanted in the audience. Some months after this fateful evening they were married, and the household at No. 17 Quincy Street was established, which became the centre of brilliant hospitality. This house was torn down when President Eliot retired from his long task at Harvard; but the Bee will never forget the many delightful evenings it has passed at 17 Quincy Street, and though the bricks and mortar have disappeared our memories picture again the bright scenes which can never be forgotten.

Her new responsibilities as the wife of Harvard’s head seemed only to make Grace love her old associates the more. She managed to continue a very regular attendant of the meetings of the Bee, although it must often have been difficult to escape other engagements on those Friday evenings. She seemed to give a touch of romance to the Bee, coming from a world of wide social and educational interests into our busy midst, always the busiest of workers and the readiest to help. She was the centre of a group whose names I could easily mention, her special admirers, for it was our invariable habit to break into little sets of chosen ones who were most congenial to one another. It was one of our glories that we were not afraid of “cliques,” but quite frankly allowed our preferences full scope and cheerfully showed partiality to those we loved best.

Alice James left a classical remark for us to remember when she said: “It is astonishing how fond we are of the Bees, even of those we don’t like.” But in choosing a neighbor for an evening’s sewing, this universal sisterhood was rightly ignored.

Some of us not only sewed like devotees at the Bee meeting, but also took garments home to finish. Marriages now became frequent events and we grew less amazed at their occurrence. New members were voted in to take the place of the Bees who had flown away to New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, and even to Germany, Norway, and England. Those who went only as far as Newton, Boston, or Brookline could still reach Cambridge on Fridays, as could also those who moved to Lowell or Andover.

We passed through numerous changing fashions in dress. Hoop-skirts diminished in size, grew very small, and happily at last were seen no more. Sleeves became so tight that we could with difficulty bend our arms, and then so large that it needed nearly as much material to make a pair of sleeves as to make a skirt.

For a long time we wore waterfalls! Let me hasten to say that this was an arrangement of the hair which had no relation to running water. The back hair was thrown forward, a little cushion was placed against it and fastened, and the hair fell over this smoothly and was pinned underneath. I cannot resist the temptation to speak of the curious hair of the present, 1923, for this fashion also will pass by, although the covering of the ears has gone on for about ten years. In the girl’s eagerness to cover her ears, she often pulls her hair down lower and lower, until it suggests the whiskers which her grandfather used to wear. But this is a tempting digression which requires curbing. No member of the Bee wears her hair thus. It is only her daughter or grand-daughter to whom the ear is a forbidden member.

Several Bees married men connected with Harvard College and continued to live in Cambridge. Several who did not marry lived on in the dignified old houses, Colonial or Victorian, of their parents and kept the beauty of the old days in their surroundings.

As the century drew to its close, it became more and more rare for a Bee to have a parent left, and a few gray hairs began to sprinkle over our brown and gold and black heads. We began to show in our faces, which had always been so fresh and young, the marks of time’s passing.

When one of our members came back to Cambridge after a long sojourn in Washington and attended the first Bee she had seen for years, her heart ached to find a group of almost middle-aged women. They had the same features as of old, the same little gestures and mannerisms, the same voices. But wrinkles were beginning to change the old freshness. Figures were beginning to broaden, teeth were less white, eyes were less clear. The world seemed to shake under her feet! The returned Bee’s own looking-glass had already told her that one Bee was changing, but to find the whole group of twenty or thirty beginning to grow old was at first desolating. We know now that at the end of the century we had not yet met our friend, Old Age. That came later and much less painfully.

A detached record informs me that in 1887 the Bee suffered one of its futile attempts to become methodical, and voted solemnly that the president should be elected every three years. The result was that we kept our presidents as long as they were able to preside and never gave them up until marriage or failing health or death forcibly removed them.

Our first president, Susan Dixwell, married and went to live in the State of New York. She has often sent us photographs and messages, and once each Bee received from her a pair of white bed-shoes, knitted for us by her own devoted hands, hav-ing blue and pink borders in memory of the old-time socks of red, white, and blue. Next came Grace Eliot in 1867 who, I think, served until her marriage.

Our next president was bright and entertaining Mary White. There is no record to show how long we flourished under her cheerful guidance. The size and vitality of the Bee tell the story of constant prosperity.

When Mary White died, Lizzie Simmons was elected president and her reign was long and superb. Her ever-present humor, her brilliant talk, her great dignity, lifted us into a realm of never-flagging activity and happiness.

Our meetings became brilliant social occasions. The simple little suppers of our mothers were things of the past. We now had ornate dinners in our own houses. We dressed carefully, with old lace and jewels or trinkets from across the sea. Our china was often rare and curious, while old silver, ancestral and otherwise, was resplendent. Flowers glowed in the centre of the table, and the efforts of cook or chef made us sit long while our sewing lay awaiting us in the parlor. Our witty ones, Mamie Warner, Lizzie Simmons, Alice James, tossed the talk across the table until we were in gales of laughter.

Ice-cream grew to be our established dessert, and it often happened that a silence fell upon us just before this handsome confection appeared, in the midst of which Lizzie Simmons would remark solemnly, “The ice-cream hush!”

Sometimes one of us, on the way to a large reception or other function, would stop, dressed in evening dress, and take dinner with the Bee. On such an occasion Lilian Farlow, tall and Grecian, made a noble picture and we all gazed proudly and fondly at our beauteous companion. We commented on such parts of her costume as struck our fancy. To remark upon one another’s clothing has always been a prized prerogative of the Bee. Even on ordinary occasions we were apt to receive a volley of remarks over some new gown or necklace or way of doing the hair, all of which we accepted as a matter of course.

Long ago Lily Hoppin became our secretary, “because she owned a fountain pen and knew how to fill it.” Whether she was born in this capacity or whether she was ever voted for I do not know, but she has long kept an account of our absences by writing in a little book the letters “ab” for those of us who were absent. Of anything like “the minutes of the last meeting” I have never heard.

These were the years of peace, during which we had altogether forgotten the sound of the beating of drums and the marching of feet, when we had long known nothing of the knitting of socks, when we felt no special thrill when we caught sight of the United States flag, unless perhaps it met us suddenly while we were travelling in some foreign country.

We had the excitement of welcoming a new century and with it came the transformation of a world.

CHAPTER III: LATER YEARS

This is the period of the small changes which have been creeping in amongst us — a little deafness here and there, a little halt in the gait, spectacles on the nose. Is this too sad to record? No, because it is the road ordained from the beginning, and we walk it together.

Many a time on a winter evening after dark I have stood on some doorstep, waiting for the maid to come and admit me to a Bee, while near me a lighted window would reveal the room inside where a group of silver heads were bent over their work. How well I knew each head and the knotting of its hair! I know the faces, quiet and humorous, that belong to the heads and I feel a momentary desire to pray for a benediction upon them all. I know how it will seem, a moment later, to be amongst them, making my way to the basket, helping myself to work and finding a seat unassisted while the chat goes on undisturbed.

The Bee has never been exactly a social unit. That is, a member of the Bee may know as little about the daily life of another member as would be the case if one lived on Brattle Street and the other in China. Yet we call one another by the first name and greet each other affectionately once a fortnight. I maintain that this friendly and unsuspicious habit is one of the reasons for the brilliance and vivacity of the Bee. There could be no assemblage more opposite to the spirit of a Church Sociable than is our scintillating Bee. Is it a Sewing Circle, a dinner-party, or a Woman’s Club? None of these. We are sure that it is unique. We arrive at any hour before, or even during, dinner. We bow or shake the hand of those already assembled, kiss and embrace one or two, then go to the basket which stands on the floor. The newcomer must discover the basket for herself and pick out a piece of sewing. Then she goes to the table and, after some searching, she unearths thread and needle, taking the latter from a red velvet needle-book in the shape of a large B. After this she finds a seat, near the light if possible, and is ready to sew a leisurely seam while she is gradually drawn into the talk, unless she prefers to sit perfectly still, a silence which is always respected and no questions asked.

Here is the sole record made in a little book devoted to the “abs” by the secretary. It is dated 1892: “On February 5th, 1892, L. Horsford presented the Bee with 4 scissors in a case. Immediately after this L. Gage used the button-hole scissors for the first time.” This is, when examined, not one of the most important events in the history of the Bee, but it is the only one, apparently, which was considered worth recording. Some of our events have been indeed memorable, and a short account of them will be found in a subsequent chapter. These events are called back by memory alone. They took place in the midst of our busy lives, were heartily enjoyed, and then for a time they were forgotten. But later years have given them a new value as we look back and recall the numerous marked episodes that came to us, because we were members of the Bee, and as far as mere reminiscence can make them live again we like to picture them to ourselves afresh.

Probably we shall have no more expeditions to distant towns. These call for more physical strength than is now ours. I noticed with some surprise that when, this summer, Eleanor Jackson proposed having a Bee at Beverly, the plan, after discussion, was dropped. Not long ago how gladly we should all have flocked to the sea!

It was during the nineteenth century that postal cards came into use. At first we were somewhat scornful of them, many people sniffily declaring that they should never, never use them. Lily Dana speaks, in her diary, of her efforts in collecting the members of the Bee for meetings in the old days. We evidently gave the invitations verbally, walking from house to house for the purpose, and this was often a somewhat difficult task. The Bee soon wisely adopted postal cards and sent notices, laconically worded, to announce the place of meeting, adding “R.S.V.P.” in the corner. Now and then the invitations were sent in rhyme, which put the Bee on its mettle at once and the answers came flying back in often very amusing verse.

During this time the meetings of the Bee became very large. More new members were voted in, married women living in Cambridge, people who probably never had heard of “The Banks Brigade.” Some of these were distinguished in some line of accomplishment. They rapidly assimilated the Bee atmosphere and were as completely Bees as if they had been found amongst the redoubtable sixteen.

Our meetings were large enough to tax the ingenuity of the housekeepers. Twenty-four people to be seated at dinner and fed with numerous courses only caused us to pull ourselves together and make the event as beautiful as possible. About once a year several Bees combined to give a charming luncheon at the Oakley Country Club, always in spring when forsythias were in their glory. Sometimes we were invited to the Colonial Club in Cambridge — the basket always being on hand as it was in the private houses. One or twice we assembled at a feast at the Mayflower Club in Boston. On one of these occasions Carrie Brewster and Lizzie Simmons, just returned from Italy, gave each of us a silver Venetian coffee spoon. At the Brunswick Hotel too we made merry as the guests of Eleanor Jackson or Alice Wells. I have still on my bureau the Japanese wooden saucer holding a china cup which Grace Eliot brought from the East, and Lily Hoppin’s gifts from Greece were welcomed with enthusiasm. There were also little wicker cages which were souvenirs of one of Mary Longstreth’s Bees, little cages each containing what the Japanese call a singing bee. They had been ordered expressly for us from Japan by the generous Mr. Sharp, a member of Mary’s household of whom you shall hear again, for after Mary had died, he had a Bee. I think it was the only one ever held by a man.

We invariably went to the dinner table in pairs in a procession, one Bee inviting another to walk with her. No rule was observed for this rite other than perhaps the taller one acting as gentleman. Place-cards were almost unknown and often a small supplementary table was necessary. The hostess led the way, escorting the guest, for we not infrequently had an outsider with us, or a favorite sister. The president sat opposite the hostess at the table. It has been remarked that the Bee has been singularly free from gossip.

There was discussion at one time as to whether every one should be compelled by statute to sew while at the Bee, but after some debate the matter was dropped, and happily we had amongst us some who very seldom touched a needle. These, not being in the habit of sewing at home, saw no reason for doing it at the Bee, and their reposeful attitude and that of those who brought knitting added to the general charm and variety which marked our meetings.

I find myself speaking in the past tense, being oppressed by the historical consciousness, but these Bee habits continue still, though I notice that more and more we are a little less energetic about our work than formerly. Eyes are growing dim, perhaps, or tiredness is more observable. It is only within the last few years that our festive suppers, or dinners, have been replaced by lunches. Going out in the evening, for women of seventy-six and seventy-nine, is becoming difficult. Our Bee luncheons are merry and full of chat, but the softening effect of time is gently falling on them, and they are not as sparkling as the evening feasts of old. This does not depress us. There is a sweetness and gentle cheer in the atmosphere that keeps our meetings fresh and beautiful. At our last Bee, in June, 1923, at Grace Eliot’s, fourteen of us were together at luncheon. Grace herself was with us, though for some years she has been an invalid and has not attended meetings of the Bee.

Now and then we enjoy the festivity of a business meeting. I purposely call it a festivity, for it is usually so treated by the Bee at large. I can see now the gleam of fun in the eyes of our president, Lizzie Simmons, as she took her place to preside on these occasions. Strict adherence to parliamentary law was quite ignored. Our treasurer, Alice Wells, kept us in touch with the needs of the hospital and the poor, and we could depend on her to tell us how many nightgowns and surgical towels to make and how much they would cost. Gertrude Sheffield knew always of the needs of the Avon Home, where for many years she was a trustee.

The business meetings of the Bee were approached in very festive mood. They occurred just after dinner when, seated in a circle around the charming living-room of some large house, we were quite in the vein to be flippant and full of repartee. After much discussion of an irrelevant but most entertaining kind, some vote might get itself passed, and whether or not we acted upon it in the future depended upon the exigencies of the moment.

Suddenly, on the first of August, 1914, like a great tidal wave unforeseen and dealing destruction, came the World War, when England, France, Russia, and Italy, and afterwards the United States, fought against Germany, Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria.

After a long pause the Bee was again busy with socks and with sewing for the soldiers. The war engrossed our thoughts and energies to the utmost. It was not enough to sew on Fridays, but a series of morning meetings went on for two years, when the Bee met at the house of Mary Cobb to make dresses, aprons, and underclothing for the Belgian orphans who were crowding by the thousand into France.

Ah! that tragedy of Belgium! It still reverberates around the world. Hundreds of Belgians were driven from their homes, leaving little children behind in barns and cellars. Children were found in strange places and were picked up and sent to the countries ready to receive them. America sent food to Belgium even before she sent soldiers, and the Bee was very active, not only with sewing, but with its interest in the Cambridge Branch of the Special Aid to the War Relief, a large organization of women of which Lilian Farlow was at one time the presiding officer.

There were emergency Bees at her house, summoned suddenly to fill a demand from the Red Cross Society for more shirts and stockings.

These four dark years were the saddest the world had ever known. Cambridge was full of camps, temporarily built to hold the recruited soldiers. One of these entirely covered the Cambridge Common. Marines were drilling in front of the Widener Library, and large bodies of serious-faced youths in khaki were forever marching through the streets of Cambridge to the beat of drums. After many years, again the beat of drums!

Our festive dinners became much simplified and we went back to repasts like the suppers of the Civil War.

When our Government called for a great loan to be collected throughout the country to defray the enormous expense of our entering the war, the Bee stepped forward so generously that one day there came a note from Lilian Farlow reading as follows:

“Dear Bees, this honor-flag comes to you as subscribers to the Victory Liberty Loan, and I hope you will give it a warm welcome to the Bee basket as well as to your hearts and homes.”

I am quite sure that this three-cornered emblem of honor will never desert the Bee basket and that it will continue to decorate the room where we meet each fortnight to the end.

In the spring of 1918 a large procession of all the trades and organizations in Cambridge was planned, to march through the streets and proclaim the importance of the Liberty Loan. Lilian Farlow, in her patriotic zeal, determined that the Bee should be represented in the procession — the Bee which had worked for soldiers in three wars and had knitted socks by the thousand. She engaged a large truck belonging to the Manhattan Market, and this she fitted with rugs and easy-chairs, making it like a room. In large letters on the side the words “The Bee” told the outside world what we were. Ten of us, with our knitting, sat in the truck and rode through the cheering multitudes on the curbstones. Whenever among the crowd a veteran of the Civil War happened to be standing, he gravely saluted with the military salute the suggestive truck, and at least once I think his eyes moistened. Ten of us white-haired workers enjoyed the sensation of taking part in a solemn procession, a somewhat curious and novel experience.

The four years of the Great War passed by. Even this at last was over, though at the time it had seemed interminable. But it has left the world in a state of chaos which in its turn seems to be without visible end. What can be the outcome of the fierce hatred amongst the nations of the world, the straining competition, the jealousy, the want of honor and justice?

1. Sixteen, including Miss Bragg. — E. E. D.

2. September 27, 1866. — E. E. D.