The ‘Gerry’ of ‘Gerrymandering’ was one of ours, co-writer of the Bill of Rights and a vice president

By Marni Zea Clippinger, 2022

It is hard to find a news story or an opinion piece about the upcoming midterm elections and the imperiled state of the U.S. democracy without coming upon the word “gerrymandering.” This term denotes the redrawing of electoral districts to give an advantage to one political party over another. What is the story behind this frequently used expression? Who was the “Gerry” behind “Gerrymandering”?

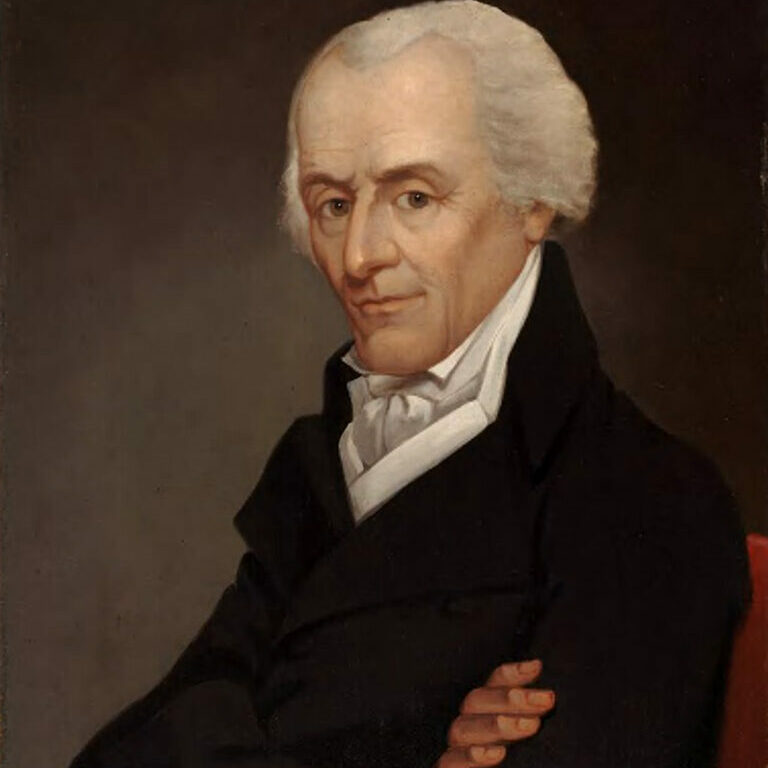

The person credited with the dubious distinction of being the “father” of partisan redistricting is onetime Cambridge denizen Elbridge Gerry (1744-1814). While it’s not a name heard frequently around Cambridge today, he was a well-known national figure before, during and after the American Revolution. Gerry was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. He co-wrote the Bill of Rights and was a member of the Continental Congress and delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He served two terms in the House of Representatives, two terms as governor of Massachusetts and, in 1812, was elected vice president of the United States under James Madison. For all his many accomplishments and extensive service to our country, what Gerry is most often remembered for today is his creative use of redistricting to increase his party’s majorities.

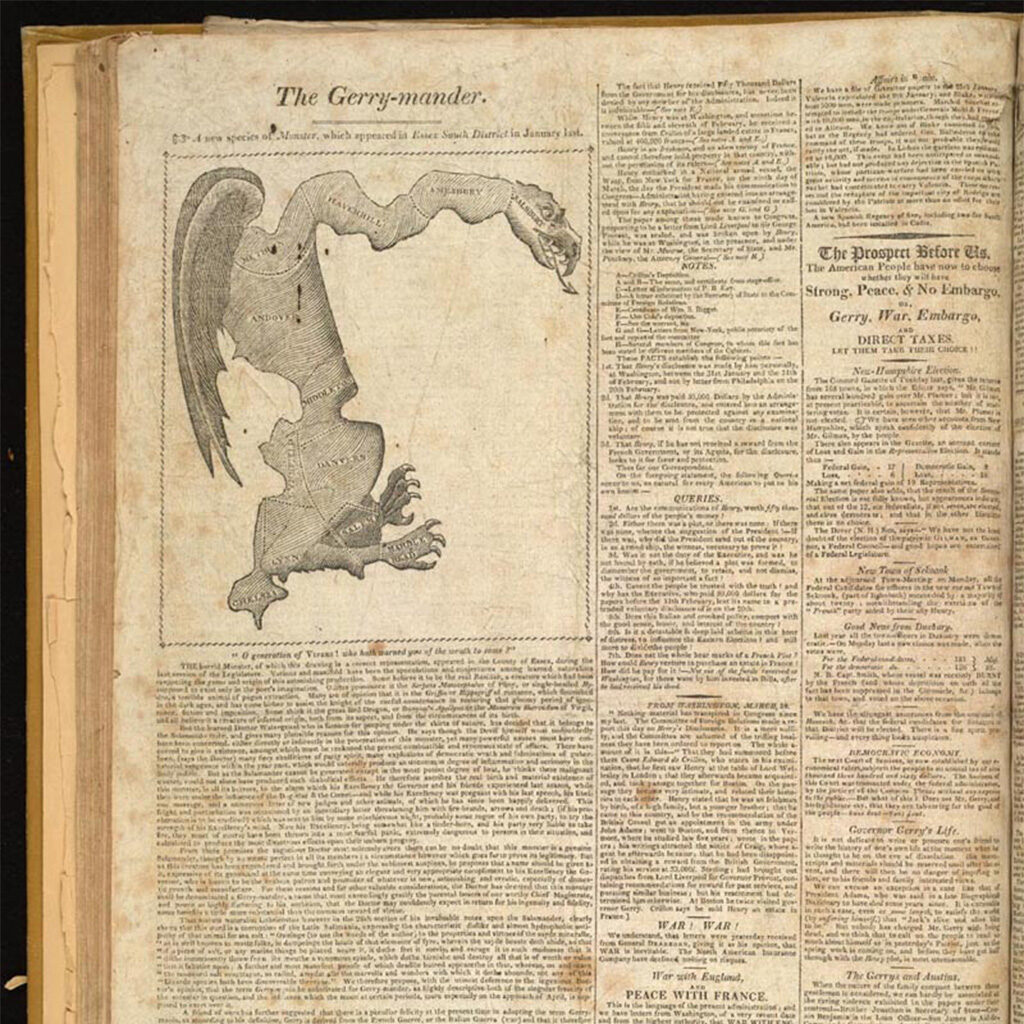

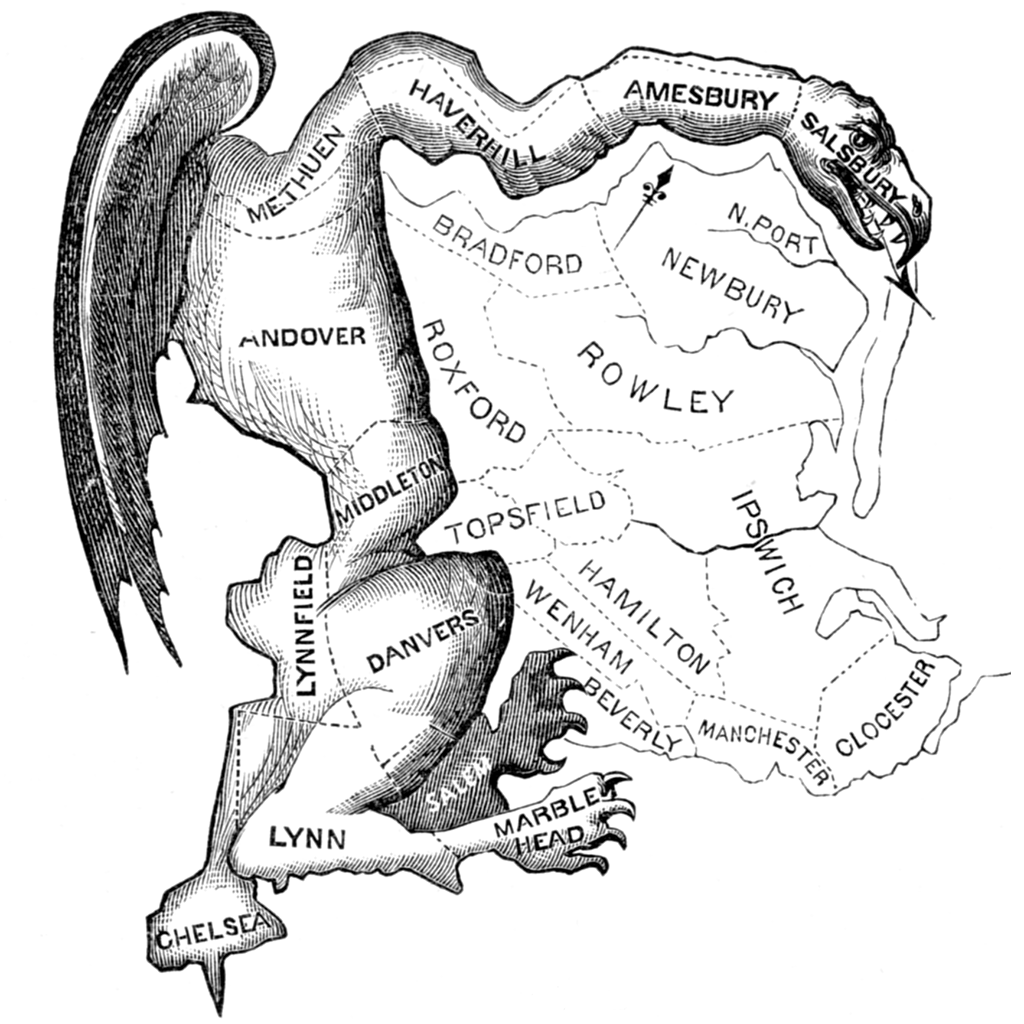

In 1812, during his second term as governor, Gerry signed a bill that redrew electoral boundaries in South Essex County to secure a victory for the Democratic-Republican Party. The redrawing resulted in the Federalist vote being concentrated in a small number of districts and the Democratic-Republicans being well distributed across many districts. The strange shape of the resulting electoral map did not go unnoticed, and became the target of criticism and ridicule.

On March 26, 1812, the Boston Gazette published an illustration, believed to have been drawn by Elkanah Tisdale, that portrayed a map of the new Essex district as a menacing salamander with teeth and claws, with the title “Gerry-mander: a New Species of Monster.” The redistricting worked for Gerry’s Party: The Democratic-Republicans won 29 seats, compared with the 11 won by the Federalists. Ironically, Gerry was defeated in his run for a third term as governor in that election, although he was elected to vice president shortly thereafter.

What else do we know about Gerry, a man whose name is associated with a practice that has had such a destructive effect on democracy? As a onetime Cantabrigian and the second resident of “Elmwood” – the Brattle Street mansion that is today the Harvard president’s house – he seems to have captured the attention of early participants of History Cambridge (formerly the Cambridge Historical Society). While much has been written elsewhere, to learn more about the man behind the portmanteau, we need look no further than the History Cambridge website. There are numerous articles about him in the Cambridge Historical Society Proceedings. For example, in her 1918 paper, “Gerry’s Landing and Its Neighborhood,” Mrs. (Mary Isabella) S.M. de Gozzaldi provided this biographical overview:

Elbridge Gerry is the only Vice-President of the United States whom Cambridge can claim. He was the son of Thomas Gerry, a merchant of Marblehead. He graduated at Harvard in 1762, and ten years later represented that town in the Provincial legislature. He married the daughter of Charles Thompson, of Philadelphia, an accomplished and beautiful lady, who had been educated in Europe.

(Gerry) was a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses, and of the Provincial Congress at Watertown in 1775. It was he, who with Azor Orne was at a meeting of the Committee of Safety and Supplies at the Black Horse Tavern on the road to Lexington, who warned Hancock and Adams, who were sleeping at the Clarke House, that the British were coming, and so saved their lives.

Gerry was elected governor of Massachusetts by the famous “Gerrymander.” He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and was sent by President Adams to France as commissioner during the French Revolution. While he was Vice-President of the United States he died on the way to the Capitol, was buried in the Congressional Burying Ground, and by special act of Congress a monument was erected over his grave bearing this inscription “Every man though he have but one day to live should devote that day to the good of his country.”

A longer, more vivid (and gossipy) biographical sketch can be found in “The Owners of Elmwood: A History and Memoir” by Lucy Kingsley Porter, read to the Cambridge Historical Society on May 31, 1949 (and found here on pages 68-76). Among many other things, we learn about Gerry’s involvement in what became known as the XYZ Affair, an unsuccessful attempt to negotiate a treaty with France to settle several long-standing disputes.

President John Adams sent Gerry, along with John Marshall and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, to France in 1797. Marshall and Pinckney soon left in disgust in response to demands for bribes from the French foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand and his subordinates. Gerry stayed on at the insistence of the French to continue negotiations. As a result, he was criticized severely and ultimately ostracized by his Federalist colleagues, who viewed his remaining in France as a sign of disloyalty. Due to these events, Gerry left the Federalist fold and joined the Democratic Republicans who felt that he had saved the country from war with France.

Various articles describe Gerry’s personality as cunning, obstinate, contrarian, contradictory and unpredictable. For example, while he was a fierce proponent of independence and believed in a strong central government, he refused to sign the Constitution, fearing it would take too much control away from the states and lead to conflict and monarchical rule. Once it was ratified, however, he came out strongly in its support.

Like most leaders – and most people – Gerry was a complex character. Deeply and passionately involved in countless aspects of the founding of the country, Gerry clearly took his responsibilities seriously and rose repeatedly to the occasion when asked to serve. Given all that he contributed, it is unfortunate that the thing that he would probably least like to be remembered for is the very thing that keeps his memory alive today.

Additional reading about Gerrymandering, its impact on democracy, and how mathematical modeling is being used to try to fight it: “Gerrymandering Explained” by the Brennan Center for Justice; and “Can computer simulations help fix democracy?” published this year by The Washington Post.