Native Americans thrived in the ‘Great Swamp,’ marshy headwaters that we know of as Alewife

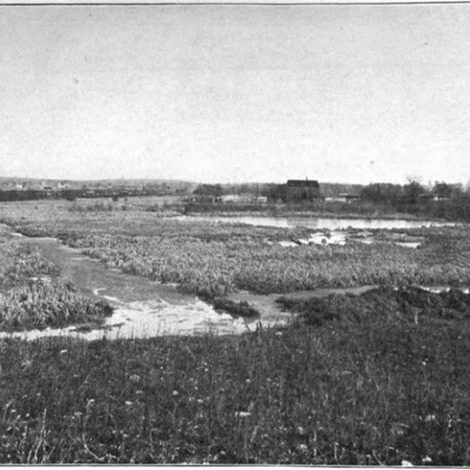

Above image: Wetlands of the Alewife in 1904, before the Little River was channelized. (Photo: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

By Marjorie Hilton

Imagine it is mid-April four centuries ago, in the area we now call Alewife. The women of the longhouse are preparing storage pots and baskets. The men are repairing fishing nets. The alewife and the blueback river herring will soon begin their annual journey from the ocean near where Boston is today to their freshwater spawning places up the Missi-Tuk – meaning “great tidal river.” This we call the Mystic.

This would have been a time of celebration, of storytelling and of teaching the traditional ways to the next generation. Elders passed on their knowledge using ritual dance, musical instruments, stories and songs. In early autumn, the people returned to their longhouses near the land we call “Alewife.” A matrilineal tribe, the women owned the longhouses, which held several families.

The women have started fires and are preparing fish and shellfish brought back from their summer encampments by the ocean. Fish and game are smoked and preserved using salt collected from the ocean during the summer. Other food is dehydrated by drying it in the sun. They dig grounds in preparation for growing, giving special attention to planting the “Three Sisters”: corn, beans and squash. Remains of the alewife fish not eaten are placed in the ground with seeds and used as fertilizer.

Women in the “Missi-Tuk” headwaters in the Alewife may have planted peas or grapes in this area. Nuts and berries were eaten fresh but, more importantly, were dried and pounded into meal, boiled or crushed for their oil. Fresh water had to be hauled (to the longhouses and smaller summer lodges called “wetus”) and kept clean for drinking and cooking. Other water is needed for crops. In autumn and winter camps, plentiful supplies of pure water are gathered from nearby streams and springs such as the Menotomy River.

The Menotomy, now called Alewife Brook, was described as a “beautiful outlet” that undulated its way through the marshes and meadows from Fresh Pond to the Missi-Tuk. The Little River, a tributary, was the outlet of Spy Pond and joined Alewife Brook near today’s Alewife MBTA station. Today, the Little River and Alewife Brook, channelized in some places by concrete, are the heirs to the Menotomy River, draining the Alewife area into the Missi-Tuk.

Water collection might have been the job of the children, and making twig brooms. Women and children collected wild berries, greens and herbs for food and medicines. In addition, they used mortar and pestles in their daily activities and made baskets and sleeping mats from the rushes that grew along the Alewife wetlands.

Women fashioned clay found nearby to make pots – clay which in the mid-19th century became an expansive resource extraction industry in the Alewife lowlands. Kilns could have been made by piling large rocks together. Perhaps animal bladders sewn together became bellows. The people used these pots for storage and preservation. The meat of deer, bear and other game was put into fat and stored in these pots. Corn and other foods were boiled in clay pots. At the summer ocean camps, fish and shellfish were often prepared – perhaps akin to today’s clambakes.

Early clay pots were probably not suspended over the fire, but set into a small amount of earth or ash with the fire kindled around their bases. Women might have decorated the pots with lines, dots and perhaps stamp impressions – rather like decorating a pie crust.

Women made clothes from animal skins and furs. The men of the tribe hunted and fished at camping areas. In the summer camps by the ocean, they might have gone on whale hunts. Men were responsible for protecting the tribe. They fashioned tools and weapons. They were responsible for mining any quarriable stone. Men hunted and fished using arrow points fashioned from rock outcrops found on present-day Churchill Avenue in North Cambridge, where the rock was easily quarried. (There is no acknowledgment on this street of such important activity.) The men hunted birds and small animals in the marshes, and gathered the traditional natural resources of the landscape.

The men used stones of different sizes for hammers, anvils and nutcrackers. They fashioned scrapers to dress skins and to make bowls and dishes. Burning the center out with fire, men then used scrapers to hollow out logs to make canoes. Two canoes might be lashed together to be made more seaworthy for whaling on the open ocean. Canoe building would have been important – they were also used as transport to the summer campgrounds along the marshes that once surrounded what we know of as Boston Harbor.

Canoes not taken to the summer grounds could freeze in cold weather and might develop cracks. To preserve them, they would be sunk in the water (perhaps in the marshes) to prevent drying out, then restored in the spring. People find buried canoes when digging in marshes today!

In general, we can assume that the people trapped alewives in a weir spanning the brook near today’s Massachusetts Avenue, hunted birds and small animals in the marshes and used the traditional natural resources of the landscape. Little River next to Cambridge Discovery Park and Route 2 has been channelized, but maintains some elements of the natural ecology of meadow grass and swamp willow, and small parts of it are being restored by an environmental group, Green Cambridge.

The land along the Missi-Tuk River and down through the marshy headwaters in the Alewife was plentiful with game in most seasons. In the winter, the men might have made snowshoes for hunting deer and turkey.

Though the people would go back to the same area each year, they were careful to vary their planting or hunting annually. They would try to go to adjacent regions, giving the land and animals a chance to replenish.

Children were born into the mother’s clan. They were cared for not only by their parent, but raised collectively by members of the tribe. They probably were related to most of the tribal members. They were raised and instructed in rituals, history and the “livelihood work” of the tribe. Children followed the routines of their parents and learned by doing. The children were employed to keep the birds away from the planted fields.

Of course they had toys, but their games often did double duty: having fun and developing a skill. One toy was made by attaching a bone circle to a string with a stick at the other end. The object was to toss the bone circle and catch the bone circle onto the post. Games of this sort gave a lot of eye-hand coordination practice and exist to this day. Children played kickball, and the boys gained experience using a small “atlatl,” a spear thrower. Girls played with dolls fashioned from cornhusks.

Elders were responsible for teaching the customs, music, rituals and history, with the tradition of storytelling as their main tool. Elders were respected, honored for keeping the tribal traditions alive and passing them on. They kept the ancient medicine “ways” alive to be practiced by the tribe.

Summer villages were located near the ocean to use the resources found there, more separated at the seashore than during farming season. Families lived in round structures made of saplings covered in bark – the wetus – made and owned by the women and usually big enough for only one family.

So who were the people of the tribe living, hunting and fishing in the Alewife marshlands along the Menotomy River and tidal flows through the Missi-Tuk? The area we know today of the Little River and Alewife Brook, stretching between Fresh Pond and Spy Pond in Cambridge, Arlington and Somerville?

They were part of the Mass-adchu-set (Massachusett) tribes, which lived on land that stretched at least from Duxbury, south of Boston, to Cape Ann in the north and at least to Concord in the west. A tribe was founded by a group of family bands that came together, and the leader was called the sachem.

The tribes of the Alewife area were called the Neponset and Pawtucket bands of the Mass-adchu-set; both bands paid tribute to the Mass-adchu-set sachems. Their language was a dialect of Algonquin. Today, through a language-reclamation project, the tribe is once again speaking the ancestral tongue.

- You can help restore the Native American narrative in the Missi-Tuk headwaters. For PondFest 2023, the seventh annual Earth Day event from Friends of Jerry’s Pond, a leader from the Mass-adchu-set tribe will guide volunteers – with the help of artist Ross Miller – in the building of a demonstration fishing weir. Information on PondFest is here.

Marjorie Hilton is an archivist and exhibit planner at the Old Schwamb Mill in Arlington and works in research and exhibit planning at the Weston Historical Society.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.