Joyce Chen started with a 250-seat restaurant, went to 350 and only grew her empire from there

by Deb Mandel, 2022

I recently began working as a volunteer for History Cambridge, updating the 2011 Culinary Cambridge website written by Rain Robertson. Digging through the Cambridge Public Library’s Historic Cambridge Newspaper Collection has been a great opportunity to revisit some of my favorite restaurants. My best experience so far has been speaking with Stephen Chen, son of Joyce Chen, to review information and enrich the restaurant’s history with photographs and personal stories. In honor of May being Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we salute Joyce Chen, her restaurants and her family legacy.

Joyce Chen was Boston’s first real celebrity restaurateur and holds indisputable importance in U.S. culinary history. In the same era Julia Child was changing America’s palates through French cooking, Chen was doing just that with regional Chinese, introducing dishes such as Peking duck, hot and sour soup and moo shu pork.

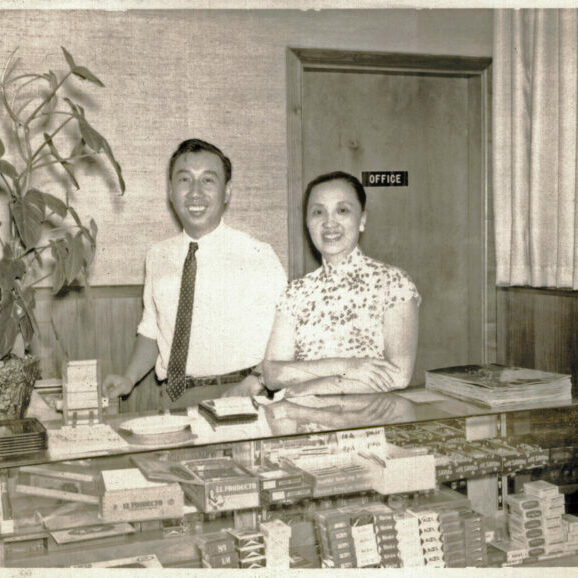

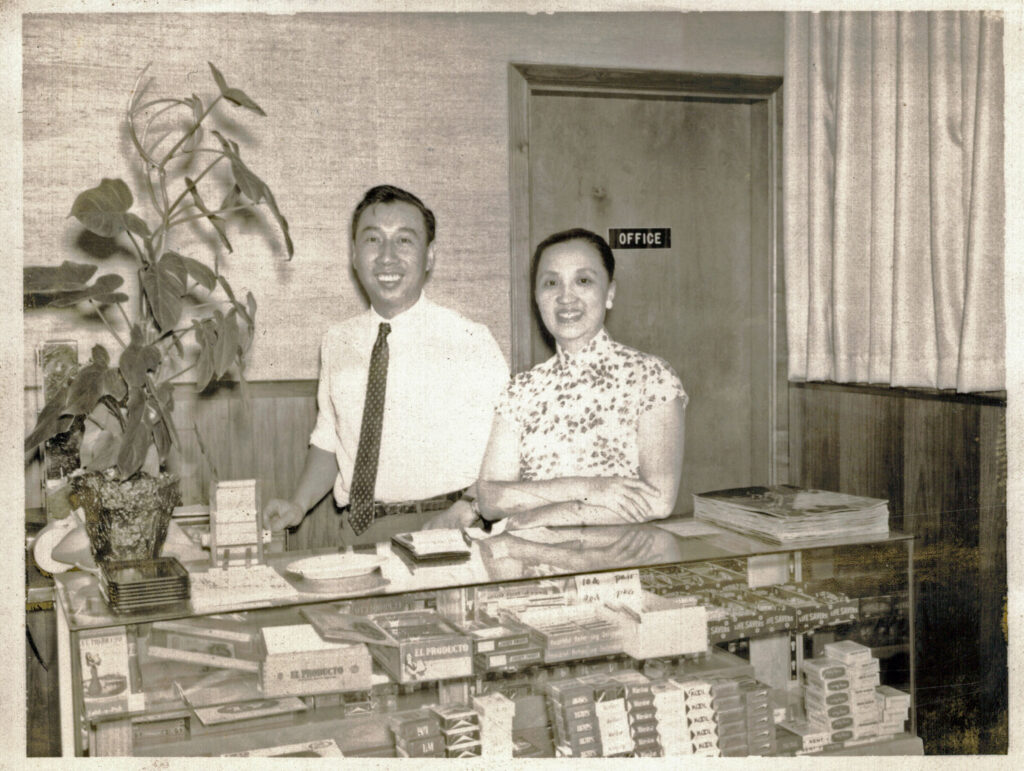

Chen left China in 1949 and opened her first restaurant in 1958 at 617 Concord Ave., Cambridge Highlands, with 250 seats. A skilled entrepreneur from the start, she regularly advertised Tuesday and Wednesday “all you can eat” dinner buffets for $3; these included turkey and ham to attract newcomers. The lines were out the door, so they played fast-tempo music to speed up the lines. During this early period, the restaurant also offered American food to customers unfamiliar with Chinese food or too timid to try it. American chop suey and chow mein were initially offered, but later dropped from the menu’s second printing as Chen’s more authentic dishes became popular. The restaurant also offered takeout and party facilities.

As in many immigrant families, the Chen children helped out in the restaurant. From the beginning, Henry, the oldest son, Helen, the middle daughter, and Stephen, the youngest, were on hand. At age 6, Stephen began his career by filling duck sauce and mustard containers.

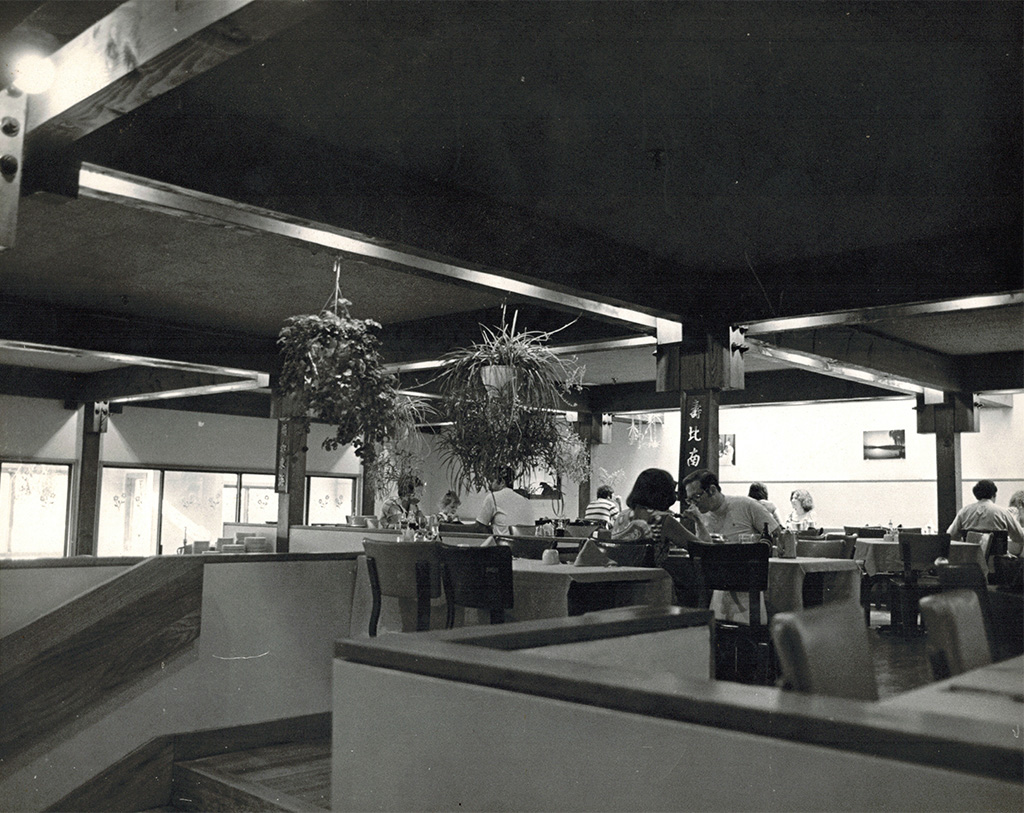

In 1973, Chen opened her 350-seat 390 Rindge Ave., North Cambridge, location. It was on two floors, with a kitchen in the basement where chefs specialized in five primary cooking styles: Kan Shao, Kung Pao, Ma P’o, Yu Hsiang – all Szechuan – as well as Mandarin Moo Shi and Shanghai cuisine. A perfect example of Chen’s ethos was her clever coining of the term “Peking ravioli” to entice Americans, making the pan-fried meat potstickers a household word in Boston and beyond.

Chen, a descendant of a war hero in China, became a pioneer in her field. After Nixon visited China in 1972, a new trade agreement enabled her to import needed ingredients. She also aspired to make Chinese ingredients and utensils accessible to the American public. Joyce Chen Foods imported and sold lines of kitchenware, and she self- published “The Joyce Chen Cookbook” in 1962. In the early 1960s, Chen taught thronged cooking classes at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education. In 1967, she had her own national PBS show, “Joyce Chen Cooks,” filmed at the WGBH studios and using the same set as Julia Child’s “French Chef.” The show became popular internationally.

In 1971, Chen established Joyce Chen Products, featuring knives, a cutting slab and a wok that Chen redesigned for use in modern Western kitchens. Her first return visit to her native country in 1972 was filmed and shown on PBS as “Joyce Chen’s China.” In June 1974, Chen spoke at the Cambridge Forum on the topic of “What’s Happening in China?”

Chen’s restaurants were packed with students, working people, and celebrities alike. Through the years, she developed relationships with Julia and Paul Child, Henry Kissinger, Danny Kaye and Beverly Sills.

The onset of dementia in the early 1980s diminished Chen’s ability to manage her restaurants, and her children’s responsibilities increased. Some public appearances continued: In 1983 she autographed her cookbook at the Harvard Coop and demonstrated her “Peking Pan”; in 1985, the Cambridge YWCA honored Chen with the “Outstanding Achievement Award for Business and Industry” at a “Tribute to Women” luncheon. Chen died in 1994. The Rindge Avenue Joyce Chen Restaurant was the last, closing in October 1998 after a successful 40-year run.

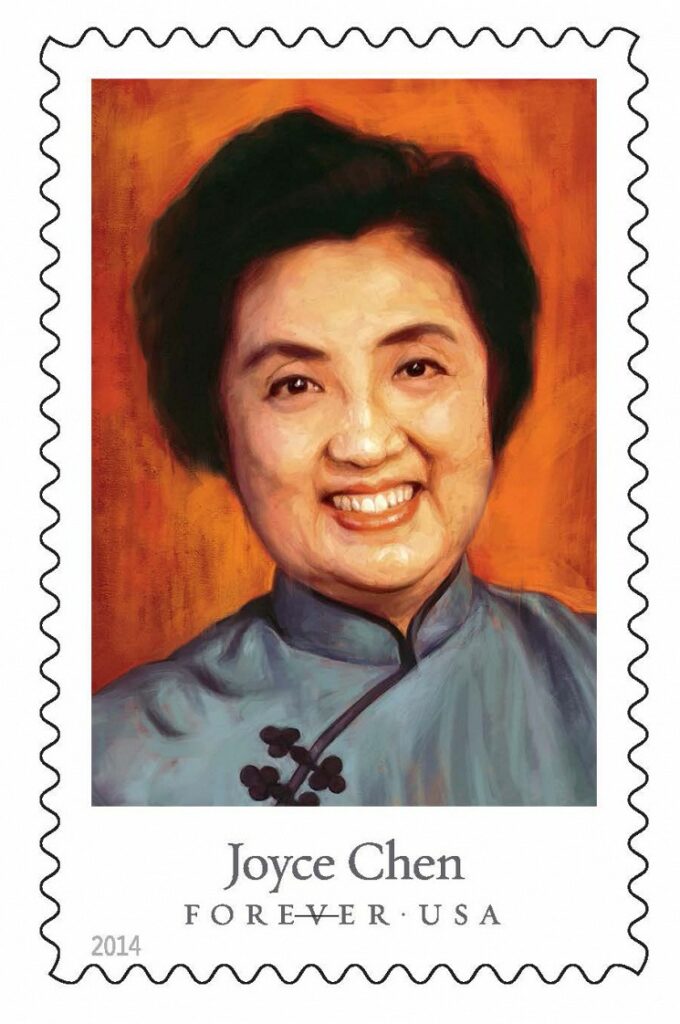

In the words of former Harvard president Nathan Pusey, Joyce Chen’s will be remembered as “not merely a restaurant, but a cultural exchange center.” In 2001, Friends of the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge named Joyce Chen “person of the week” and led a tour in her honor, and in 2014 Chen was honored with a Forever stamp as a pioneer in Chinese cuisine.

Joyce Chen’s legacy lives on in a number of Boston area restaurants started by former chefs that worked in her kitchens. Her son Stephen, president of Joyce Chen Foods, has continued to manage the company and its informative website. Her daughter Helen, a leading Asian culinary expert, continued to manage Joyce Chen Products, which she sold in 2003. She later began a consulting arrangement with Harold Import, a kitchenware distributor in New Jersey, to handle a product line called Helen’s Asian Kitchen.

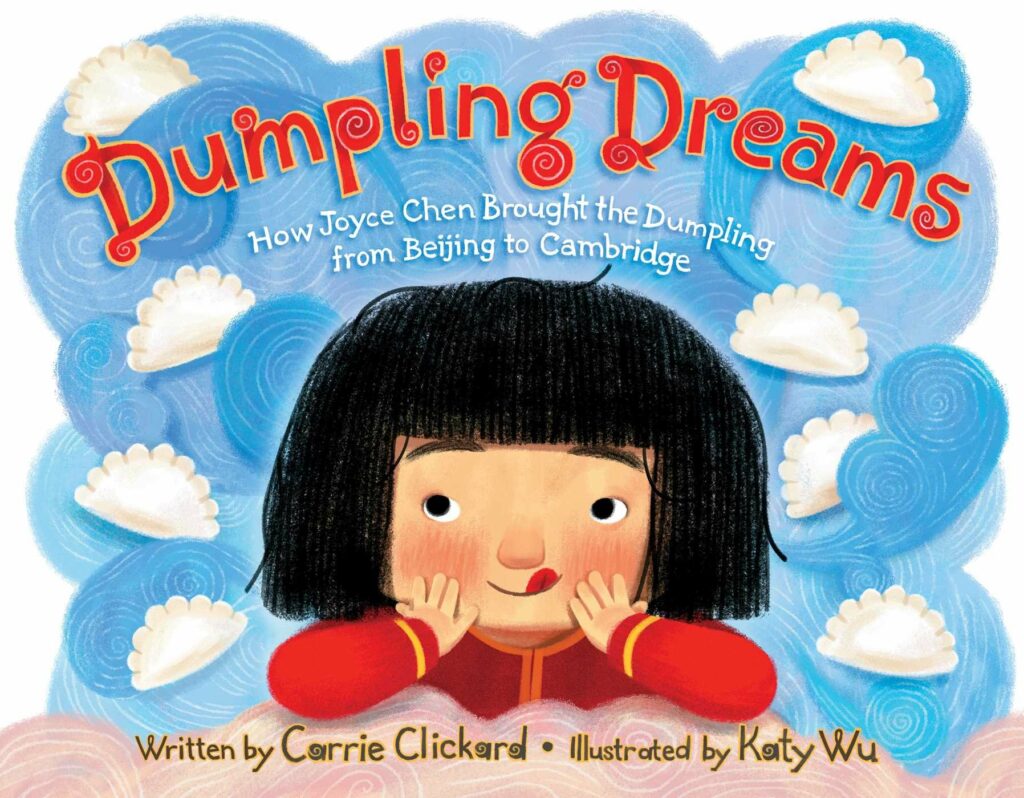

And to interest the next generation in cooking, a picture book called “Dumpling Dreams: How Joyce Chen Brought the Dumpling from Beijing to Cambridge” was written by Carrie Clickard in 2017 – another wonderful tribute to Chen and a surprise to the family. Clickard died in 2020.

Do you have memories of a Joyce Chen restaurant? Share them with History Cambridge on this feedback form!

Deb Mandel is a History Cambridge volunteer.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.