Indigenous scholars put up with missionaries, Harvard’s Indian College and ‘praying towns’

By Fatimah Ali, 2022

The history of Indigenous people in the place we call Cambridge is vastly untold and underrepresented, yet important to understand to comprehend the roots and depth of the cultural genocide that Native Americans faced over centuries within Massachusetts and the United States as a whole. Indigenous scholars, who were instructed under Colonial education systems, have similarly received very little recognition despite their impact. They disrupted the colonists’ “conviction of Colonial dominance” over the Native people. They used their learned and observed skills and the Colonialist teachings thrust upon them to their advantage to benefit themselves and their communities. James Printer and John Sassamon are among the many examples of Indigenous people – often apprenticed to Christian missionaries – who used assimilation to their advantage to reclaim their humanity and rights.

Though few written records exist concerning Indigenous presence on this land before its colonization, the founding of New Towne in 1630 served as a trigger for the exclusion of Indigenous life from the area. Later named Cambridge after the English Cambridge University, the village soon developed from plowed land, a church and a meetinghouse into a larger center of education, ministry and governance with the founding of Harvard College in 1636, as well as the influence of town founder Thomas Dudley, governor during this time. The creation of the Harvard Indian College in the 1640s was key to the assimilation of Indigenous people into the small English community. Very few ultimately graduated during the school’s short history, though, due largely to death from disease.

The Native American tribes that lived in the surrounding areas were the Massachusett and Wampanoag. Since the town’s inception, the presence of Indigenous people was influential, even in deciding the town’s location. Though there was a path leading to the ocean, the young town was largely surrounded by wilderness, leading to the construction of walls and ditches such as Windmill Hill (the present site of Ash Street), to protect against wolves and Indigenous people whom they viewed as equal threats.

The high mortality rate caused by the transfer of disease from English Colonials to Indigenous people meant few groups of Native Americans remained in the area for long.

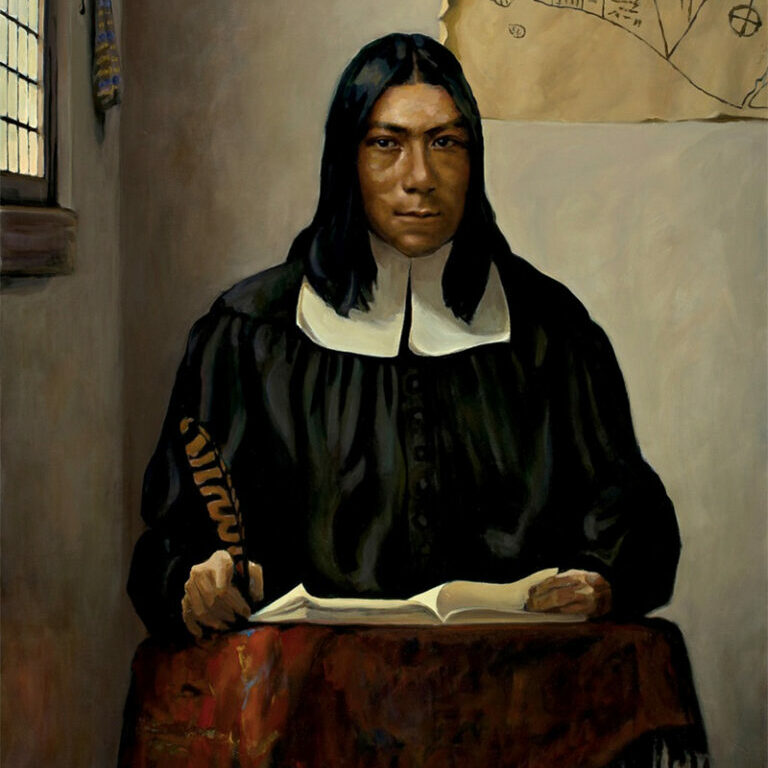

Some Indigenous people formed professional relationships with the colonizers, though. One was Sassamon, an Indigenous scholar, translator and apprentice to Puritan missionary John Eliot during the early to mid-1600s. Sassamon, the first Native American to attend Harvard College, helped Eliot in many of his Indigenous language translations – created in an effort to assimilate the Native population into Colonialist culture.

Sassamon also served as a preacher, teacher and interpreter of the Algonquin language, acting as an intermediary between the English and Indigenous peoples in disputes and exchanges of land. He was bilingual and bicultural, able to travel between the two cultures while not being fully immersed in either. Some believe it was this, and Sassamon’s role as an informant for the English, that led to his murder in 1675, the trigger for the brutal King Phillip’s War.

Nonetheless, Sassamon played a significant role in gaining and maintaining indigenous people’s rights through his own cultural fluency, despite attempts by Colonials – Eliot among them – to strip him of his culture through assimilation.

Another Indigenous man who faced assimilation through the imposition of English literacy and education was Wowaus, or James Printer. Printer was an Indigenous typesetter, teacher, Christian missionary and leader educated at Harvard College and played a role in the spread of English literacy among his students in Hassanamesit (now known as Grafton) and Waeuntug (current-day Uxbridge). His English literacy and connection to Indigenous and Colonial cultures also allowed Printer to serve as an adviser and translator to Metacomet, or King Phillip, during the King Philip’s War.

Like Sassamon, Printer was an apprentice to Eliot. He lived mainly in Hassanamesit, one of the many Massachusetts “praying towns” – established by the English Colonial government for Indigenous people wherein the practice of Christianity and becoming “civilized” to English standards was central. Indigenous people were often taken to live in these towns by force, faced with the alternative of exile.

Indigenous missionaries who lived in these towns and preached the principles of Christianity bridged the gap between the Colonials and Indigenous peoples by teaching English literacy. As Sassamon did, missionaries often served as intermediaries and spokespeople for their communities, having the ability to negotiate land rights and ownership in disputes with the English. While this often led to them owning land, they were also able to provide inroads toward land autonomy for other Indigenous peoples.

Sassamon and Printer’s journeys exemplify the varied nature of assimilation and its use by Indigenous people to fight settler Colonialism and regain their liberty and rights as a people.

History Cambridge will provide resources to further explore the histories of Indigenous peoples in Cambridge in the forthcoming Indigenous Peoples History Hub. Follow our progress at historycambridge.org.

Fatimah Ali is an intern this summer with History Cambridge researching the history of Indigenous people in Cambridge. She is a rising senior at Wellesley College studying architecture with a concentration in urban studies.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.