‘Here Lies Darby Vassall’ fall art installation makes the invisible visible at Christ Church

By Beth Folsom, 2022

If Cantabrigians have heard of Darby Vassall, more than likely their knowledge centers on the story he told later in life of his boyhood encounter with Gen. George Washington. Soon after arriving in Cambridge to take command of the Continental Army in the summer of 1775, Washington saw 6-year-old Darby swinging on the front gate of the John Vassall house. Darby had been born into enslavement there, as his mother, Cuba, was enslaved by John Vassall, while his father, Tony, was enslaved by John’s aunt and uncle, Penelope and Henry Vassall. When Darby was very young, he was given to George Reed of South Woburn; after Reed succumbed to injuries sustained at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Darby Vassall made his way back to Cambridge, where he was reunited with his family at the home of their former enslaver.

John Vassall and his family had abandoned their Cambridge estate for the protection afforded Loyalists by the British troops in Boston in 1774 before moving to Halifax, Canada, in 1775. The estate was commissioned as the headquarters for Washington during his nine-month stay in Cambridge. On that July day in 1775 when the general encountered young Darby in the front yard, he asked the boy to work for him. Upon asking what his pay would be, Washington scolded him for his impudence; in retelling the story, Darby often remarked that Washington “was no gentleman, [wanting a] boy to work without wage.”

Although free in name, the Black Vassalls remained legally enslaved, but they stayed at the Brattle Street estate and ran it throughout the Siege of Boston. In 1781, the Massachusetts state Legislature took control of the property, but agreed to pay Darby’s father, Tony Vassall, a dozen pounds per year as compensation. Upon Tony’s death in 1811, the Legislature agreed to an annual 40-pound payment to Tony’s widow, Cuba Vassall, who died the following year. Between the time he was a 6-year-old child bargaining with Washington and a 92-year-old man preparing for the end of his life, Darby Vassall was a son, husband, brother and father. He was a caterer, a property owner and an activist with religious, political and economic societies. Upon his death in 1861, he was buried in the Vassall family tomb at Christ Church, Cambridge, after nearly two decades carrying a note from Catherine Russell, granddaughter of Henry and Penelope Vassall, giving her permission for Darby to be interred in her family’s crypt.

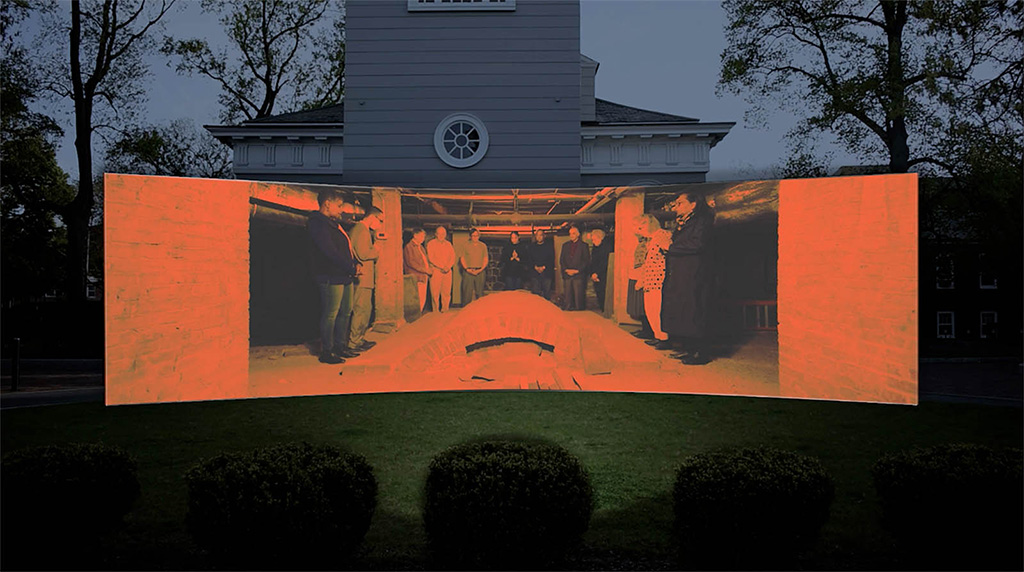

A temporary art installation on view on the front lawn of Christ Church seeks to bring Darby Vassall’s long and rich life to a wider audience. In “Here Lies Darby Vassall,” Nicole Piepenbrink, recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s 2022 Design Studies Thesis Prize, examines the perceived invisibility of slavery in New England through the lens of Christ Church, the final resting place of Darby Vassall. The inaccessible, largely unknown Vassall Tomb in the basement of Christ Church is shared with the public via a looped video projection telling the story of this church’s collusion with, dependency on and profit from the slave trade that provided economic foundations for the establishment and growth not only of this church, but of Cambridge, Massachusetts and New England. In so doing, Piepenbrink highlights the connections between plantation slavery in the Caribbean and on the Southern mainland, northern fortunes built on the backs of enslaved workers, and the philanthropic endeavors of many of the region’s prominent individuals and families.

“Here Lies Darby Vassall” is on view nightly from 6 to 8 p.m. until Nov. 6 at Christ Church, Cambridge, Zero Garden St., Harvard Square. On Oct. 27, Piepenbrink will discuss her project as part of the Fall Lecture Series co-sponsored by History Cambridge and the Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Park. This program is free and open to the public, but registration is required and can be found here.