Swimming in a Countercultural Sea

By Dick Cluster, 2010

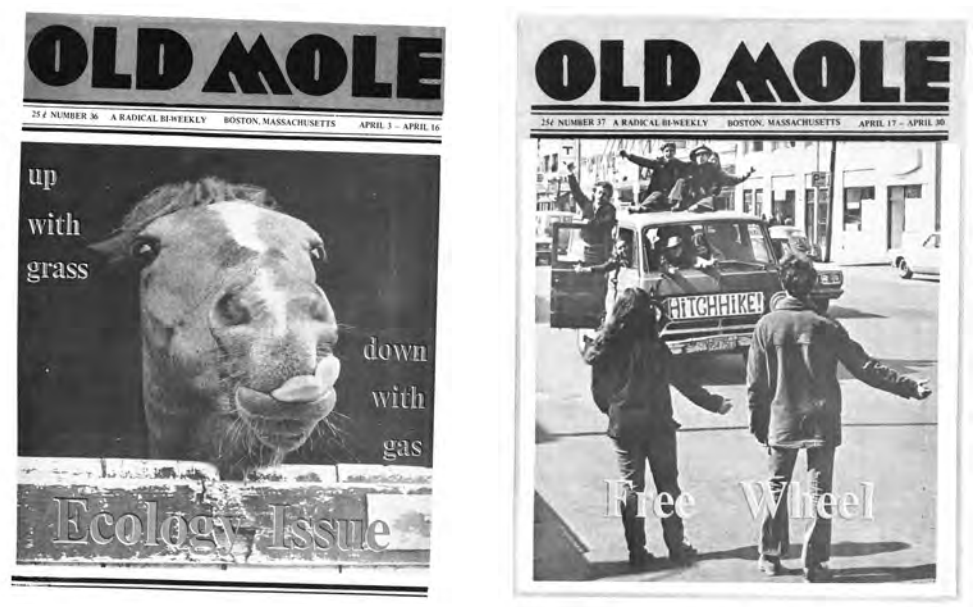

For much of its brief existence between 1968 and 1970, the 16-page tabloid underground newspaper Old Mole featured a column of short items called Zaps on page 4.

Here are two:

- “PEACE CORPS EXPELS 13 FOR ANTI-WAR ACTIVITY –– a real, live headline from the Washington Star.”

- “If it isn’t in the New York Times Index, maybe it didn’t happen.” [cut and pasted from an ad in the Times]

The point being, there was a lot that happened that didn’t get reported, and a lot that was reported incorrectly. Or, let’s say, we saw it from a different point of view. The Old Mole, whose nameplate pronounced it “a radical biweekly,” grew out of the radical student movement of the 1960s.

Its staff members, paid and volunteer, had been or were active in the national movements for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam, for shaking universities loose from their liberal or conservative adherence to the status quo, for women’s liberation, tenants’ rights, welfare rights, abortion rights, school reform, labor organizing . . . that list might go on and on, and some of the words (let’s try “school reform”) would not mean what they mean today. In the national spectrum of the “underground” press (that is, poor, alternative, and illegitimate in the eyes of authoritative voices in whatever field), the Mole was more toward the “politico” than the “hippie” end, but all the papers swam in the same countercultural sea.

The paper drew its name from an obscure speech by Karl Marx. The version on our masthead said, “We recognize our old friend, our old mole, who knows so well how to work underground, suddenly to appear: the revolution.” That appealed to a sense that, while no new American revolution seemed anywhere near a point of triumph, one did seem necessary.

There was a lot of exciting movement and heresy out there, and who knew where it might lead? The paper’s job was to offer some journalistic help.

The Old Mole published 47 issues from September of 1968 to September of 1970, mostly out of a storefront and basement office at 2 Brookline Street in Central Square. The first issue covered, among many other things, the demonstrations at the Democratic Party’s National Convention in Chicago; the last, the Black Panther Party’s Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. About half the coverage was local. The masthead (“staff of the Old Mole, an anti-profit institution”) listed 20 to 30 people who had worked on a given issue of the paper, none with ranks or titles. I don’t think there were ever more than four paid staff (at something like $140 a month). Most of the staff had other jobs; they also got free bundles of the paper to sell on the street. Most were college graduates, some from local schools, others who had gravitated to Boston from elsewhere. A few were high school or college students or dropouts or grad students. They were about half female and half male, and almost all were white.

The paper circulated by subscription, street vendor sales, and newsstand and bookstore sales. The cover price was “15¢ cheap” for the early issues, 25¢ later on. Subs were free to prisoners and soldiers, and there were quite a few APO and FPO addresses on our list. The subs to soldiers and sailors went out inside a brown wrapper; letters we got back often said the paper provided the only touch of sanity in their lives. Press runs were about 8,000-10,000, as best I can recall. Donations as well as sales supported the paper.

The only issue that had a second printing was the one in which we reprinted letters and memos liberated during the 1969 student strike that described Harvard’s CIA links and its administration’s duplicity in trying to get around student and eventually faculty pressure to end its ROTC program. Two printings of that issue sold out. “But how can we know these files are authentic?” asked reporters from what we called the straight, or bourgeois, or pig press. A few months later, Daniel Ellsberg started copying the Pentagon Papers. Two years later, after six years of growing antiwar organizing and education, the New York Times and Washington Post finally printed those truths about the war. The underground press, including the Old Mole, had something to do with that.