Cambridge’s candy history is more than just a sweet story

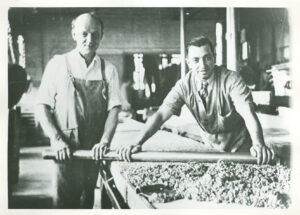

Above image: A confectioner mixes chocolate at the Daggett’s Chocolate factory in Cambridge in the mid-20th century. (Photo: History Cambridge)

By Beth Folsom

Last month, History Cambridge made its TikTok debut in a video produced by WBZ Radio. The piece, highlighting Cambridge’s role as a center of candy-making, features an interview with program manager Beth Folsom about the city’s confectionary past. The TikTok format is limited to two minutes or less, making for a fun and fast-paced overview of the subject, but there is more to the story of Cambridge’s candy industry, particularly its ties to the plantation slavery that dominated the Caribbean economy in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

At its peak in the mid-20th century, Cambridge boasted 66 candy companies, including Squirrel Brand, Daggetts and Necco, and Main Street was nicknamed “Confectioners’ Row.” The candy industry began in the 1760s, when an Irish immigrant named John Hannon built a chocolate mill on the Neponset River in Dorchester. The introduction of the steam engine in the 1840s created a boom in the candy market, and many companies moved from Boston to Cambridge, where land was cheaper.

Over the course of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, wealthy Cambridge families maintained ties to the sugar plantations of the Caribbean; many of the city’s white elites not only enslaved people of African descent on their estates in and around Cambridge, but also owned and/or profited from the enslavement of vast numbers of people in Jamaica, Antigua and other islands. The proceeds from this enslaved labor helped to fund private residences and public institutions throughout the city, and continuing economic ties to the Caribbean sugar economy greatly contributed to the rise of Cambridge as a candy-making hub.

During its first eight decades, the candy industry, like so many others in the Northeast, was made up mostly of British and German immigrants, many of whom had worked in food production in their home countries. Beginning in the mid-1800s, these workers largely transitioned to other industries, and the legions of Irish immigrants fleeing from the Potato Famine took their place. A generation later, at the end of the 19th century, the Irish were in turn replaced by new arrivals from Italy, Portugal, Lithuania and other parts of Eastern and Southern Europe – as well as Barbadians and other Caribbean immigrants seeking to escape from their islands’ collapsing economies. Beginning in the early 20th century, these immigrants from abroad were joined by Black migrants leaving the South to find better socioeconomic and political conditions in the North, including the racially integrated schools of Cambridge.

The beginning of the end for Cambridge candy came with the rise of the big national candy conglomerates, namely Hershey’s, Nestle and Mars. These companies understood that distribution had changed. You had to get involved with the big chains, and you had to be more centrally located and be able to ship everywhere. Success in the industry became less about who was producing the best candy and more about who could get to market first. Independent confectioners were hard pressed to match the conglomerates’ distribution levels, national marketing efforts and slotting fees – the price companies pay to have their candies front and center of the register at the grocery store.

Today, the only remaining large-scale candy company in the city is Cambridge Brands, producers of Tootsie Rolls and Junior Mints, whose chocolate aroma wafts through the air around its manufacturing plant outside Kendall Square, but a number of smaller candy shops carry on the city’s confectionary traditions. To learn more about Cambridge’s history as a candy capital, including the industry’s connections to plantation slavery and the region’s immigration history, check out History Cambridge’s self-guided tour and sign up for our newsletter to find out about upcoming events and programs.

Note: In its video, WBZ erroneously identified Beth Folsom as an employee of the Cambridge Historical Commission. While this is incorrect, History Cambridge works closely with the commission and is grateful for its support and partnership.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.