Growing up in Cambridgeport was unforgettable for Louis Fenerlis, the child of Greek immigrants

By Gretchen G. Adams, 2023

Louis Fenerlis, owner of Louie’s Haircuts on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, considers himself to be a proud product of Cambridgeport. During recent conversations, he shared fond memories of growing up there in the 1960s and 1970s among a close community of Greek Americans, raised by hard-working, immigrant parents who were determined to give their children the childhoods they had never had. Here are some of the stories he remembered.

Fenerlis’ mother, Dina, was born in a field in Greece where her parents cultivated olives and oranges. The day after giving birth, her mother was back at work outside with the baby, feeding the baby fresh and nutritious goat milk. As soon as she was old enough to help, she worked side by side with her parents.

Fenerlis’ father’s family endured generations of trauma. They lived in and around present-day Istanbul, some in the eponymously named town of Fener. When the Greco-Turkish War ended in 1922, Fenerlis’ ancestors were forced from their homes; one was killed as he was packing to flee. They sought refuge in Thessaloniki, inside the redrawn Greek border. The local people shunned refugees such as the Fenerlises, though, seeing them as Turks rather than fellow Greeks. In 1941, Nazis overran Thessaloniki, home to the largest concentration of Jews in Greece. Fenerlis’ grandfather, Peter, operated a painting business that employed many Jews. The Nazis executed Peter along with his laborers, leaving Fenerlis’ grandmother a widow with six children to raise alone.

Only 6 years old at the time, Fenerlis’ father, John, went to work immediately to help support his family, selling cookies on a street corner. By the age of 11 he was working as a barber, trimming hair, whisking hair off customers’ necks after their haircuts and sweeping floors. Always scrambling to make money, he applied for and was hired to run errands for an upscale hotel overlooking the sea. There he befriended a long-term guest, U.S. foreign service officer Arthur Dukakis, a first cousin of Michael Dukakis, who was later governor of Massachusetts.

Knowing that his prospects for prosperity in Greece were slim, John Fenerlis applied to emigrate to the United States and was thrilled when a sponsor was found. Arthur Dukakis was equally excited until he heard of the assignment to … North Dakota. Dukakis feared that John Fenerlis, accustomed to a Mediterranean climate, would be unable to endure living in a state where temperatures plunge below zero for 50 days each year.

Crisis averted! Dukakis found a new sponsor for John Fenerlis – a Massachusetts doctor, Philip Sherwood, who owned a farm in Westwood. Nineteen-year-old John Fenerlis sailed to Boston in 1956. After living and working on the farm, he got a job as a janitor at New England Baptist Hospital.

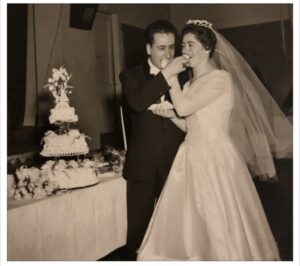

Three years later, John attended the wedding of a Greek friend. He was smitten instantly with another attendee, Dina, a first cousin of the bride who had traveled from Greece with her father to attend the ceremony. With her father as chaperone, the couple courted, marrying just one month after making each other’s acquaintance. They remain happily married 64 years later.

To be near one of the largest Greek Orthodox churches in the region, Saints Constantine and Helen on Magazine Street, the Fenerlises settled in Cambridgeport at William and Pearl streets. Their family doubled almost instantly when Dina’s father sent two of her teenage brothers from Greece to join them. Having grown up in a tiny village (population around 300) the boys went a little crazy in the big city and sometimes got into trouble. They soon calmed down and enrolled in hairdressing school, eventually becoming successful barbers.

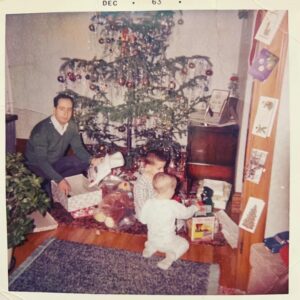

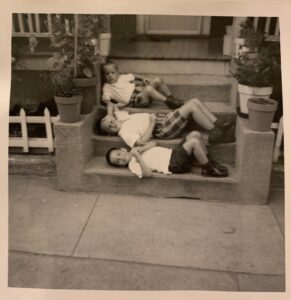

In 1961, with one son, Peter, and another (Louie) on the way, the Fenerlis family outgrew its apartment on William Street and moved a few blocks closer to the Charles River. Their new address was on the first floor of 209 Allston St. A distant relative, the proprietor of the Bradford Cafe in Central Square, owned the building and lived upstairs with his family. The apartment had (to Fenerlis) a big yard. Inside there was plenty of room for a third child, Kathy, who was born in 1964.

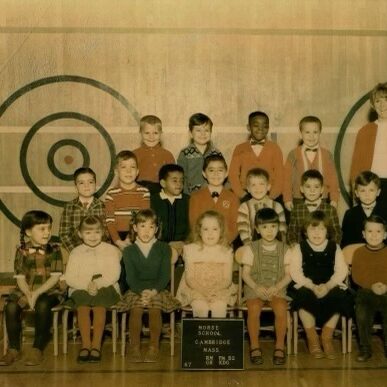

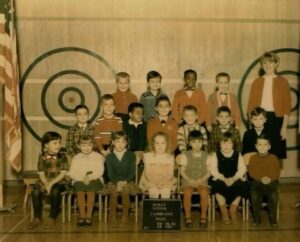

Starting in kindergarten, Fenerlis attended the “new” Morse School on Granite Street. His classmates were of African, Irish, Greek and Italian descent. Although strict, the teachers created a loving atmosphere for the children. The faculty made an effort to get to know the parents of their students, passing along background information about the families as the children moved from grade to grade. Fenerlis feels he got an excellent education at Morse that served him well throughout his life.

Although generally kind, the teachers weren’t averse to hitting children if they got unruly. In fact, wanting his children to make the most of their education, Fenerlis’ dad had specifically given the teachers permission to strike his kids if they got out of hand. After Louis Fenerlis told a lie, a male teacher approached him quietly from behind and walloped the back of his head with a textbook.

Fenerlis and his older brother walked home from school every day. They were under strict orders to remain inside until 3:30 p.m., when their mother returned from her job at the Revelation Bra factory in Central Square. Paid by the piece, she often brought lingerie home to continue stitching in the evenings. Fenerlis said he was fascinated by her work, particularly when she was sewing undergarments for full-figured women!

When allowed to venture outside in the late afternoon, he played in what he and his friends called Trash Park, at Allston and Brookline streets – the site of the first Morse School, which the city had demolished. They played basketball and street hockey on the tennis courts until suppertime. The children with whom he played in the 1960s and 1970s are still some of Fenerlis’ closest friends.

Not all of the local children were as well cared for as Louie. One boy, Joey, lived on the street with parents who suffered alcoholism. Joey once threw a rock at Louie’s head, splitting it open. Blood gushed from the wound. Fiercely protective of his offspring, Louie’s dad chased Joey down and gave him a beating, hoping this would prevent the lad from ever again laying hands on his son. Louie learned years later that Joey had been found guilty of murders and died in prison.

Fenerlis’ dad always worked two or three jobs. During the day he cut hair; at night he pumped gas at a Shell station in Brighton, but quit when a co-worker was murdered there. He found safer night-time employment as manager of the 1200 Beacon Street Restaurant in Brookline, now a Holiday Inn. According to Fenerlis, whenever he had time off, his father showered attention on his children. A self-taught musician, he made up songs for them that he performed on the guitar, harmonica, accordion and bouzouki. When Fenerlis expressed a desire to learn the drums, his parents saved the money to buy him a set – which Fenerlis still owns.

Fenerlis’ parents never had to force him to attend church services or Greek School at Saints Constantine and Helen. In no small part this was because of the dynamic priest, Arthur J. Metaxas. The priest understood children; he made an effort to get to know each of his young parishioners, and worked hard to ensure that church activities appealed to them. On Greek School nights, Metaxas drove his Oldsmobile station wagon around Cambridge, collecting kids who lived too far away to walk to the church. Fenerlis could hear the car approaching, because Metaxas allowed the children to blast rock ’n’ roll music from its radio.

A member of the choir and an altar boy (eventually the president of the Saint Andrew’s Altar Boy Society), Fenerlis was proud to play a role in religious services. During communion, he held the basket of holy bread for the priest. During funerals, he held candles around the coffins. On Friday nights during Lent, he sang solos at church services. As church members paraded through the streets of Cambridge on Easter, he carried a heavy cross.

Fenerlis said he is especially indebted to the church for introducing him to his “effervescent” wife, Helen. They have been happily married for decades, and have raised three girls.

Fenerlis attended Cambridge Rindge and Latin for only a few months of his freshman year, but long enough to endure being hazed. In the 1970s, upperclassmen at Rindge “welcomed” new students by ripping off their clothes and forcing them to run home naked. Fenerlis and a friend thought they had escaped this embarrassing ordeal by running inside the friend’s home and locking the door. But no – the older boys kicked in the door and attacked them.

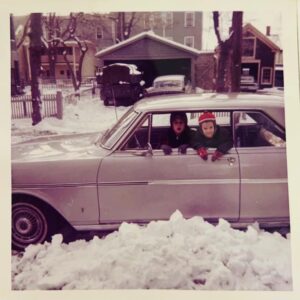

That winter, Fenerlis’ happy Cambridge childhood came to an abrupt end. His parents had saved enough money to invest in a two-family house. They opted to move to Arlington, where an extra unit would earn them more rental income than one in Cambridge, a city with rent control. Fenerlis never adjusted to the new town, where he felt other students looked down on the children of immigrants. He scraped by academically, completing so little work that he said he isn’t sure why the school awarded him a diploma.

Although he attended college for a year, generously paid for by his parents, Fenerlis was itching to begin working full time. After a succession of jobs in grocery stores and other retail establishments (including Nini’s Corner in Harvard Square), he trained to be a barber, working first with his uncle, then opening his own shop on Commonwealth Avenue. He makes certain everyone, from local luminaries to undergraduates, leaves his shop looking their best. Like his dad, Fenerlis was born with a gift for friendship and has formed lasting relationships with many of his clients and their families. Always eager to give back, he makes a point of hiring immigrants and men and women who have endured hardships that make finding work difficult.

Did you grow up in Cambridgeport? History Cambridge wants to hear your story. Fill out this Google form or email us at info@historycambridge.org.

Gretchen G. Adams is a volunteer for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.