Who Is Essential Cambridge? Part 4: COVID-19

In our last installment, we examined the role of nurses as essential workers in Cambridge and beyond, exploring the ways in which gendered notions of caregiving and self-sacrifice both elevated nurses in the public opinion and limited their ability to advocate for better pay and working conditions. In this, our final installment, we look at the current COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on those workers deemed “essential” to the continued operation of the local and national economy, particularly women essential workers. In their occupations as grocery workers, health care workers, public transportation and delivery drivers, these women’s labor has been vital to the survival of society over the past ten months. The pandemic has shed light on just how essential these workers are, but it has also highlighted the vast racial and gender inequities that have long existed in the U.S. labor market.

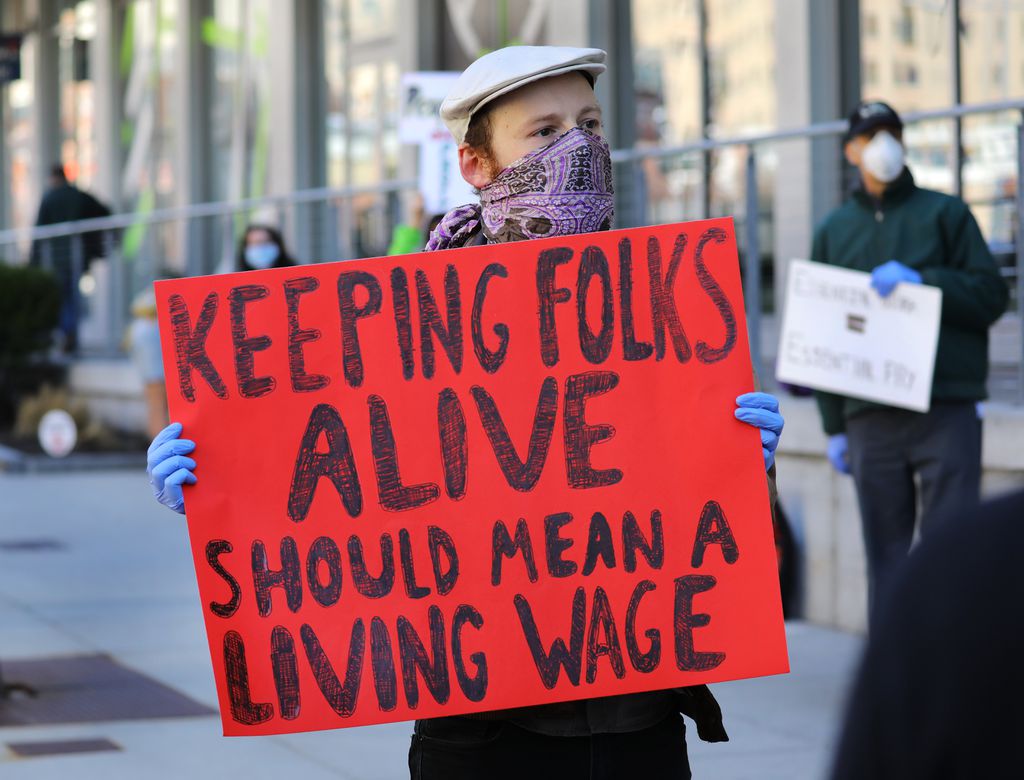

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health confirmed the first case of the COVID-19 virus in the state on February 1, 2020, identifying the victim only as “a man returning from Wuhan, China who is in his 20s and lives in Boston.”[1] Boston Public Health Commission Executive Director Rita Nieves emphasized that this was only the eighth confirmed case of the novel coronavirus in the United States, stating that “[r]ight now, we are not asking Boston residents to do anything differently. The risk to the general public remains low. And we continue to be confident we are in a good position to respond to this developing situation.”[2] By March 15, Governor Charlie Baker had ordered a 3-week shutdown of all Massachusetts schools, and on March 23, the Baker Administration issued a stay-at-home advisory requiring all non-essential businesses to close their doors.[3] Following this order, many Massachusetts residents were able to perform some or all of their work duties from home, but those in the service, hospitality, and transportation sectors were considered essential and, unable to do their jobs remotely, continued to report to work in person. These essential workers were recognized and appreciated, often for the first time, by a general public relying on their services, but they also experienced a lack of support and protection from their employers and the stark reality that they were required to risk their own health and safety to keep the shaky financial safety net of their low-wage jobs.

On March 20, even before the Governor’s stay-at-home order, an editorial in the Boston Globe remarked that “[h]ospital workers will care for the sickest among us, but it is those grocery store workers who will care for and feed the rest of us.”[4] The article went on to advise Massachusetts to officially designate grocery workers as essential for the purposes of providing increased benefits, including free child care. As the pandemic spread and more residents became infected, grocery workers began to protest a lack of protection from their employers, both in terms of wages and in provisions for their health and safety. In April, the United Food & Commercial Workers Union and the Albertsons Companies, which owns the Massachusetts-based Shaw’s and Star Market chains, embarked on a nationwide campaign to have grocery store employees designated as emergency personnel, giving them priority for coronavirus testing and access to personal protective equipment (PPE). In an interview with the Boston Globe, Shaw’s employee Lisa Wilson explained that “[e]mployees are allowed to wear gloves and masks, but the store doesn’t provide them, and workers get a 5 percent discount on the gloves it sells.”[5] Wilson also told reporters that she made $12.75 an hour and got one hour of paid sick time for every 30 hours worked, noting that she was also helping to support her parents, both of whom were out of work due to the pandemic. Despite an industry-wide response to workers’ demands for PPE, supermarket employees were among those filing complaints with the Massachusetts branch of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in April and May, alleging that their employers were not doing enough to keep them safe. According to OSHA records, “[s]ome workers said they were forced to work alongside sick colleagues. Others said they were ordered to keep working with symptoms or confirmed infections. The accusations include complaints about a lack of masks, gloves, and personal protective equipment and assertions that companies failed to adequately clean work spaces or communicate risks to employees.”[6]

Another group of essential workers who have been (literally) keeping society running is transportation workers. Drivers and other personnel working for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) have provided crucial services, particularly to other essential workers travelling to and from their jobs and to those accessing other essential services such as medical care and groceries. In August, relaxed restrictions on passenger behavior had drivers like Catisha Berment worried about a surge in virus transmission. Berment, who was diagnosed with COVID in April, was anxious about reinfection, stating that “[p]assengers, not all of them in masks, are allowed to board through the front again, sometimes standing right beside her as they load their Charlie Cards.”[7] As of the end of July, 177 MBTA employees had tested positive for COVID, although none had died; no hazard pay was provided to MBTA workers.[8]

Another category of essential worker whose continued presence was crucial, though largely unseen by the general public, was health care aides working in private homes or in skilled nursing facilities. By mid-April, Cambridge had reported over 200 COVID cases among residents and workers at the city’s assisted living facilities.[9] The owners of these nursing homes petitioned Massachusetts to allow them to bypass state-imposed wage caps in order to increase workers’ pay in an effort to retain staff, particularly the nursing aides as the lowest end of the pay scale.[10] In addition to helping them fill shifts, nursing home operators advocated for the pay raise as a means for potentially stemming the high infection rate in Massachusetts assisted living facilities. Nursing home executive Frank Romano cited low pay as a contributing factor to the spread of COVID, stating that “[m]any nursing home employees must work in several facilities to make ends meet and cannot afford to stay home during the public health crisis. As a result, many may have been accidental spreaders of the virus between their various workplaces.”[11] Because so many nursing aides lived on the edge of the poverty line, and because the nature of their work required an in-person presence, they were unable financially to stay at home during the pandemic. In addition, the piecemeal nature of their work in multiple nursing facilities not only put them at heightened risk of contracting COVID themselves, but also exposed their patients to greater risk of infection due to cross-contamination.

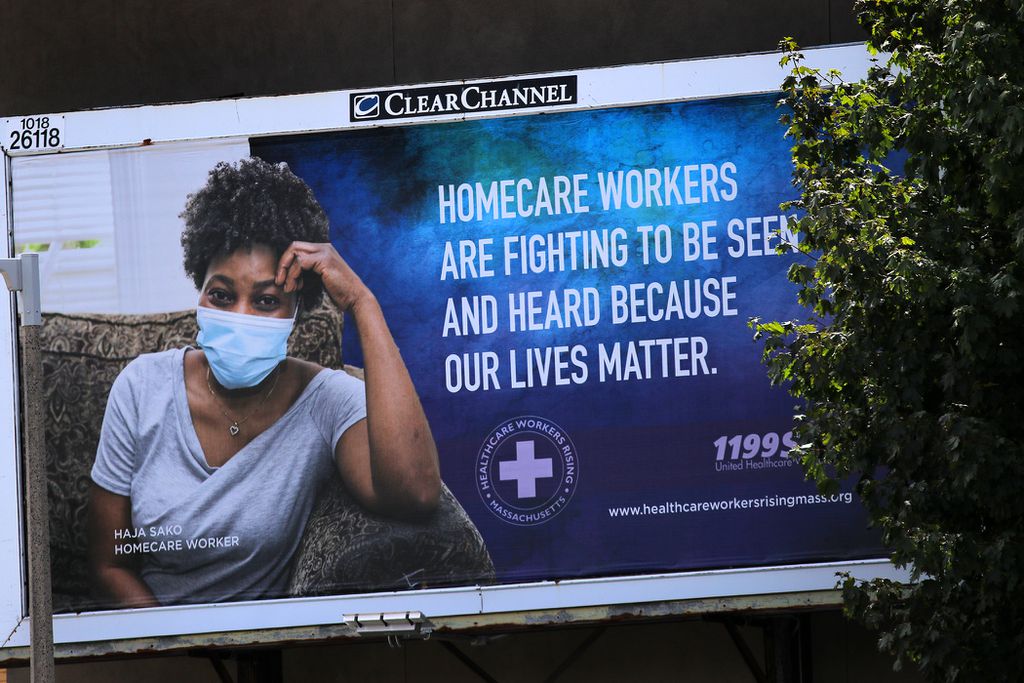

Even less visible than the health aides working in nursing homes are those assisting the elderly and disabled in their own homes. In an attempt to draw attention to the challenges facing these home health workers, the union representing about half of the 100,000 in Massachusetts put up a series of billboards highlighting what it called “the deep cracks in the overstretched and underfunded long-term care system that the pandemic has exposed.”[12] Healthcare Workers Union organizer Dana Alas told the Boston Globe that “[t]here is no system in place to make sure that the work that these workers do is respected and valued….We wanted to highlight that to the public and also to let these workers know that we see them.”[13] According to union estimates, the population of Americans 65 and older will nearly double between 2016 and 2060, and by 2026 the home healthcare workforce is projected to add more jobs than any other occupation in the U.S. The high rate of COVID infection in assisted living facilities has also led many families to reconsider placing their older loved ones in nursing homes and has expanded the demand for home health services. Yet, according to home health advocates, one in six home care workers lives below the federal poverty line, and more than half rely on some form of public assistance.[14]

The vast majority of home health workers are also women, and the challenges of performing low-wage in-person labor during the pandemic are compounded by the need to balance their work outside the home with the needs of their own families. With schools and many child care centers shut down or running at very limited capacity, working mothers are forced to make difficult choices to care for their children while still needing to perform their essential jobs. Unlike mothers in sectors that lend themselves more easily to remote work, home health workers must perform their work in person, exposing them and their families to greatly increased risk of COVID infection. But despite the need to report to jobs outside the home, they are also required to tend to their responsibilities as mothers and family caregivers, leading many to make the difficult choice to either leave their children home alone or to risk further exposure by placing their children in less-than-ideal group childcare settings—if childcare was accessible to them at all, given its high price tag compared to their low wages. According to a Brookings Institution report issued in October 2020,

[B]efore COVID-19, nearly half of all working women—46% or 28 million— worked in jobs paying low wages, with median earnings of only $10.93 per hour. The share of workers earning low wages is higher among Black women (54%) and Hispanic women (64%) than among white women (40%), reflecting the structural racism that has limited options in education, housing, and employment for people of color…..Women are much more likely than men to work in low-paying jobs: 37% of working men earn low hourly wages, nearly 10 percentage points lower than women.[15]

The report highlights not only the gender imbalance in wages, but also the racial disparities further impacting women of color. A recent analysis released by the Center for American Progress supports these findings:

Black, Latinx, and Indigenous women especially—all of whom face intersecting oppressions—are also feeling the multiple effects of being more likely to have lost their jobs, being on the front lines as essential workers, and solving their child care challenges on their own. As a result of a variety of factors, including policy choices grounded in racism and sexism, low-wage workers, solo mothers, and women of color—three groups with considerable overlap—are all too often not in the economic position to leave the paid labor force to care for their children. Women of color, and Black women in particular, have historically had much higher levels of labor force participation when compared with white women, but they also experience many more job disruptions due to inadequate child care. Women of color and immigrant women have often provided domestic labor that facilitates the employment and leisure time of wealthy and middle-class white women but prevents them from spending more time with their own families.[16]

The current pandemic has not created the gendered and racial inequities in the workforce, but has brought to the attention of white middle- and upper-class Americans the divisions that lower-class workers—particularly women of color—have been experiencing for decades.

In a year already reeling from the effects of COVID-19, the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement spurred a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, leading many activists to call attention to the “dual pandemics” of COVID and systemic racism. For many, the issues of economic and racial justice are fundamentally intertwined. According to Boston-based activist Monica Cannon-Grant, because the work of opposing and dismantling discrimination is essential work, activists leading the charge on these issues should be seen as essential workers. In June, Cannon-Grant told the Boston Globe that “[t]o be an essential worker is to show up for your community and for those who cannot show up for themselves. This is everything that activists are doing right now.”[17]

In Cambridge, the intersection of low-wage work and the Black Lives Matter movement was highlighted in June when a group of workers at one of the city’s Whole Foods Markets staged a walkout to protest the company’s policy of not allowing workers to wear masks bearing the Black Lives Matter slogan. Workers told the Boston Globe that they were told that their attire (including masks) must not include any messaging with advertisements, political statements or logos that are not company-related, and were asked to either remove their Black Lives Matter masks or leave work without pay. Protest organizer Savannah Kinzer said that she had recently completed a shift wearing a mask that said, “Soup is Good” and had not been asked to remove it, but that her attempts to distribute Black Lives Matter masks to her colleagues had been met with opposition from management.[18] Kinzer and other employees also reported that workers regularly wore shirts, hats, pins, and masks bearing sports logos as well as other issues such as gay rights, none of which had elicited pushback from Whole Foods. Over the next month, more Cantabrigians joined the ongoing protests outside the Whole Foods, including Mayor Sumbul Siddiqui, Vice Mayor Alanna Mallon, and members of the City Council.[19] In July, workers at the Cambridge Whole Foods joined their colleagues from across the country in a federal class action lawsuit against the grocery chain and its parent company, Amazon. The suit, which by August had grown to include 28 named plaintiffs, charged Amazon with discrimination against workers for their support of Black Lives Matter, a charge that the plaintiffs said was not only unlawful but was also in direct contradiction of the company’s own public statement disavowing racism.[20] To these workers, the issues facing low-wage but essential members of the labor force and those facing people of color were inextricably linked, and their calls for economic and racial justice could not be separated.

As the pandemic rages on, we are expectantly awaiting the widespread distribution of the two vaccines recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Although it will be at least several months until the vaccines are available to the general public, and several more months before the immunity they provide will allow for a return to some semblance of pre-pandemic normalcy, we can begin to predict how the lessons learned from the past year will shape our decisions as a society moving forward. The economic disparities highlighted by the pandemic are the result of longstanding policies which have privileged men over women, white over Black and brown, and two-parent over single-parent families. The economic structure in which we operate has served to keep low-wage workers in poverty, isolated from the protections and benefits offered to middle- and upper-class Americans. Long before the pandemic took hold, the lack of affordable and accessible childcare and the continued responsibility for the bulk of family caregiving put women in an untenable position; the additional blows to workforce participation and wage earning of the past year will have long-reaching effects for women. According to the Centers for American Progress,

Hard-won progress on closing the gender wage gap may also be set back decades. Increases in women’s labor force participation rates fueled the significant narrowing of the gender wage gap in the 1970s and 1980s. Women’s labor force participation reached its peak in the late 1990s, and progress on closing the gender wage gap has remained virtually stagnant ever since. Research has shown that strengthening labor force attachment is critical to increasing women’s earnings. One study found that women who took just one year out of the workforce had annual earnings that were 39 percent lower than those of women who did not.[21]

Of course, these statistics address women who, by choice or necessity, take time away from the paid workforce. This does not include the vast number of women in Cambridge and across the country whose jobs in the essential workforce have not allowed them to stay at home during the pandemic, whether or not they had children or other family members to care for. The accolades given to essential workers, and the accompanying concessions of hazard pay and free childcare (often allocated after much public pressure) must be the starting point of a nationwide overhaul of the economic and social policies undergirding the country’s workforce and its support for working families.

Throughout the twentieth century, Cambridge women have comprised a key segment of the city’s essential workforce; from their work in factories during wartime to their dominance in the sectors of teaching and nursing, to their critical service as grocery workers, transportation workers and health care aides during the current pandemic, they have kept the city and the country running, and they have done so while continuing to bear the burden of caring for their own families as well. Often seen as selfless and self-sacrificing caregivers, these women have faced tremendous obstacles when advocating for higher pay, shorter hours and better working conditions, and have seen the value of organizing in the attainment of these goals. As we move into the post-pandemic era, it is imperative that Cambridge women continue to work together across racial, ethnic and socioeconomic lines to support one another and to enact structural changes that better support all women, thereby strengthening not only the essential workforce but the city as a whole.

[1] https://www.mass.gov/news/man-returning-from-wuhan-china-is-first-case-of-2019-novel-coronavirus-confirmed-in

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Mass. Issues Stay-at-Home Advisory, Closes Nonessential Businesses, as Coronavirus Death Toll Rises to Nine,” Boston Globe, March 23, 2020.

[4] “Grocery Stores Grow Ever More Critical Amid Coronavirus,” Boston Globe, March 20, 2020.

[5] “As More Grocery Store Workers Die, Employees Call For Better Protection,” Boston Globe, April 7, 2020.

[6] “Hundreds of Mass. Workers Say Companies Failed to Protect Them From COVID-19,” Boston Globe, May 17, 2020.

[7] “Will Anything Change for the Low-Wage Essential Workers Once Hailed as Heroes?” Boston Globe, August 3, 2020.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “More Than 200 Coronavirus Cases Reported at Cambridge Nursing, Assisted Living Facilities,” Boston Globe, April 13, 2020.

[10] “Amid Coronavirus Pandemic, State’s Nursing Home Workers Will Get Extra Pay,” Boston Globe, April 14, 2020.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Union’s Billboards Depict the Plight of Home Care Workers During the Pandemic,” Boston Globe, September 1, 2020.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Why Has COVID-19 Been Especially Harmful for Working Women?” Brookings Institution, October 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/why-has-covid-19-been-especially-harmful-for-working-women/

[16] “How COVID-19 Sent Women’s Workforce Progress Backward,” Center For American Progress, October 30, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/10/30/492582/covid-19-sent-womens-workforce-progress-backward/#:~:text=OVERVIEW,gender%20equity%20back%20a%20generation.

[17] “Activists Are Essential Workers Fighting for a More Just America,” Boston Globe, June 18, 2020.

[18] “Whole Foods workers sent home for wearing Black Lives Matter masks,” Boston Globe, June 25, 2020.

[19] “Whole Foods Black Lives Matter Protests Grow as Workers Calling Out Hypocrisy Near Dismissal,” Cambridge Day, July 12, 2020.

[20] “Whole Foods Workers’ Black Lives Matter Lawsuit Grows, Expanding to Nine States and Adding Amazon,” Boston Globe, August 19, 2020.

[21] “How COVID-19 Sent Women’s Workforce Progress Backward,” Center For American Progress, October 30, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/10/30/492582/covid-19-sent-womens-workforce-progress-backward/#:~:text=OVERVIEW,gender%20equity%20back%20a%20generation.