Who Is Essential Cambridge? Part 3: Nurses

In our last installment, we examined the role of Cambridge teachers as essential workers during the twentieth century. As it involved nurturing young children, teaching was viewed by many as a natural outgrowth of women’s caregiving responsibilities within the family, and education, especially at the elementary level, was considered a profession to which women devoted themselves for noble and selfless purposes and not for economic prosperity. Our next installment explores the role of Cambridge women in another essential caregiving profession: nursing. Just as women were largely responsible for educating children within their households, they were likewise tasked with caring for the sick and injured in their families. During the Civil War, many women ventured outside of the domestic realm to care for soldiers at the front and in army hospitals―a trend that gave birth to the professionalization of nursing in the postbellum era. Emily Elizabeth Parsons, who founded the Mount Auburn hospital after returning home from her service as a Civil War nurse, is perhaps the best-known Cambridge example.

Photo Credit: Cambridge Public Library

Nursing was a suitable―even ideal―profession for women because of what was believed to be their “natural inclination” toward sympathy and caregiving. The ranks of nurses in Cambridge, as in many cities, included a fair number of religious women, particularly Catholic nuns. As members of a religious order whose vows included poverty and obedience, these women were able to devote themselves fully to their nursing duties without thought of remuneration. Describing a 1901 fair held to raise money for the creation of the Deaconess Hospital in Boston’s Longwood neighborhood, the Cambridge Chronicle explained the origins of the hospital’s name: “There are now about 12,000 deaconesses in Germany and about 1,000 in America….The duties of a deaconess are ‘to minister to the poor, visit the sick, care for the orphan, seek the wandering, comfort in sorrow, and save the sinning.’”[1] The author goes on to describe the hospital’s operational structure, explaining that “[t]he deaconess nurses are unsalaried, their support being guaranteed. No patient is ever turned away because he cannot pay….The free patient has exactly the same care as the one who pays.”[2] Deaconess nurses were unpaid, as they were supported by their religious order, and so were unencumbered by both the economic need to earn a salary and the family responsibilities that could compete with secular nurses for their time and attention.

Cambridge’s Holy Ghost Hospital, too, was run by a religious order, the Catholic Sisters of Charity. In a 1905 article celebrating the hospital’s tenth anniversary, the Cambridge Tribune quoted its annual report, stating:

No Cambridge charity is more deserving of support than the Holy Ghost Hospital for Incurables….At the present time there are 17 sisters of charity engages in the administration of the hospital, assisted by 28 employees. We desire to express our sincere thanks to one and all who have labored so untiringly for the institution and the comfort and happiness of its inmates, and we will ever pray that God may bless and reward them for their kindness.[3]

Those working for a religious hospital, especially the nursing nuns, did so for the greater glory of God and were thus removed from the petty squabbles over salary and working conditions that could otherwise plague those in the medical professions.

Although those nurses who were members of a religious order were seen as both selfless and desexualized, the nursing profession as a whole could not escape the stereotype of nurse-as-femme-fatale that often accompanied descriptions of young, attractive nurses. In a 1911 article entitled “Nurses Find Cupid in the Sick Room,” the Cambridge Sentinel noted:

[t]he trained nurse appears to play a more prominent part in the romantic news of the day than any other professional woman. Hardly a day passes but the newspapers chronicle some marriage, will, love affair or litigation in which a trained nurse figures….Venus in a nurse’s cap and gown is a most enticing siren….Men marry their nurses so frequently that the instances are beyond all counting.[4]

The romantic image of the pretty young nurse soothing the sick or injured male patient was especially prevalent during wartime. Although the United States had not yet entered World War I in 1916, its status as an ally providing aid to the British and French military included widespread support for the Red Cross and its operations overseas. That year, a report on a fundraising fair in New York noted that “[t]here were many pretty girls at the great allied bazaar in New York, but Miss Margaret Fair was acclaimed the prettiest of them all. Miss Fair was attired in a nurse’s costume and assisted Mrs. Caspar Whitney at the booth of the French wounded emergency fund.”[5] It was apparently worth noting that Miss Fair’s nurse attire was a contributing factor in her being crowned the prettiest at the fair.

Photo Credit: Heritage Auctions

Once the U.S. formally entered the War in 1917, nursing became a central way in which young women could serve both their country and their community, and nurses became role models for girls to emulate, as evidenced by coverage of the Cambridge Liberty Loan parade in 1918:

Cambridge’s Liberty Loan parade last Saturday afternoon was the largest and best military and civic display ever seen in this city….There were more than 15,000 men, women and children in line….Some of the girls of the [High and Latin] school paraded as Red Cross nurses and others as members of the Girls’ Athletic Association….Ten elderly women who have worked in four wars rode in an auto truck, all busily knitting….The Cambridge Red Cross women, led by Mrs. Charles A. Stover, president of the Cantabrigia club, made a splendid showing.[6]

Cambridge women could also contribute to the greater national effort during wartime by working within their own community to serve those in need. Declaring that “[t]he women of Cambridge are second to no community in combining intelligence with zeal in this great work,”[7] the Cambridge Sentinel praised local nurses’ involvement not only in war service, but also with the city’s Board of Health and the Visiting Nurses Association in their work with mothers and children:

The C.V.N.A. [Cambridge Visiting Nurses Association] is trying to increase its obstetrical nursing work in the homes of the poor to ensure cleanliness and proper care to those of limited means who, in spite of their financial condition, are in just as much need of adequate medical service. Last year the C.V.N.A. attended at confinement the mother of one-fifth of the children born in Cambridge, and gave care to an additional one-tenth.[8]

Supporting the health and wellbeing of children and families was an especially important part of the nationalist agenda coming out of World War I, and Cambridge nurses had a central role to play in this effort. They were also faced with an additional challenge as the war was ending: the 1918 influenza epidemic. With its proximity to military facilities in greater Boston and the use of both Harvard and M.I.T. as military training centers, Cambridge quickly saw its number of influenza cases on the rise. By mid-September of 1918, hundreds of civilians were infected in the city, and so many of the nurses at the Cambridge City Hospital were suffering from influenza that the hospital was effectively closed to new patients.[9] As the epidemic continued into the fall, schools were closed and their facilities were converted into makeshift hospital wards staffed by volunteer Cantabrigians, including many teachers. With their professional lives on hold due to school closures, these women received acclaim from patients and the wider community for their service, including publication of their names in a “Roll of Honor” in the Cambridge Sentinel. Although the high schools (at which many men served as teachers) were also closed, most of the schools converted to clinics were elementary schools, and the individuals listed in the Roll of Honor were exclusively women.[10] Given the shared stereotypes of teaching and nursing as naturally feminine caring professions, it should come as no surprise that out-of-work teachers transitioned to nursing influenza patients during the pandemic.

Following the dual challenges of World War I and influenza, Cambridge experienced a shortage of nurses―a problem which would recur periodically over the coming decades. In 1921, in response to this shortage, the Charlesgate Hospital (once located at 350 Memorial Drive, currently an MIT sorority house) planned an enlargement of its training school for nurses. The school’s founder and superintendent, Anne Radford, had served as an army nurse in Europe and, upon her return to Cambridge, vowed to put her wartime knowledge and experience to work in the service of the Charlesgate: “More than a month ago Miss Radford returned from Europe with much wonderful knowledge of what the English, French and American boys did in the world war, and it is due more or less to her varied experiences there that she intends to enlarge the hospital, with the idea of being of more value to humanity.”[11] As part of her planned expansion, Radford envisioned widening the professional knowledge and training of nurses as well as their numbers. Through a new partnership with the Boston Lying-In Hospital, student nurses completed an eight-month course in obstetrics; in cooperation with the Brookline Friendly Hospital they were able to serve a two-month fellowship in public health. And Radford expanded the coursework for all nurses to include “Histology, Anatomy, Physiology, Fever, Nursing, Hygiene, Bacteriology, Material Medicine, Dietetics, Gynecological and Obstetrical Nursing, in Surgery and Orthopedic Surgery.”[12]

In addition to the increasingly diverse and rigorous coursework for student nurses in hospitals, the inter-war period also saw a growing emphasis on nursing beyond the hospital setting. Visiting nurses provided vital services to individuals and families as part of a team of health professionals. In 1932, Dr. Donald Currier told the annual meeting of the Cambridge Visiting Nursing Association that “[t]he best visiting nurses in Metropolitan Boston I know of are our own right here in Cambridge.”[13] Currier went on to extol the virtues of the C.V.N.A. and its role in the city’s public health system:

[Public health] is a field wherein all may work, and the state has valuable material for distribution, including diet lists and household budgets which will be mailed upon application. With our board of health and its staff of nurses, our hospitals with their dieticians and social service workers, the teachers in our schools, the dental clinics with their dentists and hygienists, mothers’ classes in the settlement houses, and parent-teachers associations, as well as doctors and nurses already in the field, we ought to reach every family in Cambridge and interest all parents in the growth and development of their children, our future citizens.[14]

Currier’s description of the public health system as a network through which to reach and bolster the health of every Cantibrigian underscores the link between healthy children and a healthy citizenry, a link that intensified as the nation headed toward another World War. As they had in World War I, Cambridge nurses took their place as members of the military medical corps. Although concerns resurfaced about a possible nurse shortage, those serving as army nurses were a point of pride for the city, and local papers took every opportunity to publicize Cambridge nurses who were decorated or promoted.[15] A 1945 Boston Globe article highlighted the case of Lt. Marian Donahue, “a pretty Cambridge army nurse”[16] who had been bedridden for nine months with a mystery ailment contracted during her service in England. Interviewed at the army hospital in Charleston, S.C. where she was receiving treatment, Donahue “had nothing but praise for the combat men, for whom she served on special missions overseas, about which she would say nothing….‘You can always tell the combat men here at Lovell,’ she said, ‘even when they say nothing. For they’re the ones who never complain.’”[17] Despite her own health struggles, she maintained that “we haven’t gone through much compared with what the combat boys did,” and cautioned the reporter: “‘Don’t expect me to feel sorry for myself,’ she said. ‘I’m treated swell here. They’ve got me spoiled.’”[18] In focusing on her former patients rather than herself, Donahue exemplified the selfless image of the nurse putting her own needs and desires last, even in times of great personal trial.

Photo Credit: Digital Commonwealth.

Although Cambridge nurses, like their counterparts around the country, were lauded for their service in wartime, once the war was over they again faced the challenge of low pay and long hours. In 1946, Cambridge City Councillor McNamara “told the City Mgr. that he was ashamed of conditions there, relating to nurses’ hours, working problems, pay, etc.”[19] The city manager answered this complaint by saying that changes would be made by August 1; Counsellor Sullivan replied that the proposed pay raise of $3 per week was “an insult” and said “that he had advised some of them to go on strike, rather than accept such a sum.”[20] The nurses did not go on strike in 1946, but continued to file complaints about low pay and poor working conditions in Cambridge hospitals. A 1957 Boston Globe article cites Cambridge City Council support for a petition by nurses at Cambridge City Hospital for higher salaries and better conditions, stating that the nurses’ complaint “charged conditions at the hospital are ‘disgraceful’ and that the nurses are ‘overworked and underpaid.’”[21] The nurses in this case were seeking a raise of $440 per year, the same amount that had recently been allotted to the city’s policemen and firefighters. As both selfless caregivers and defenders of public safety, nurses viewed themselves in the same category of essential workers as police and firemen, and the rhetoric they used to argue for better wages and conditions centered not on their own economic wellbeing but the broader protection of those in their care. Nurses who were overworked with too many patients could not properly care for each person entering the hospital, and the push to improve conditions was presented as an extension of their self-sacrificing professionalism rather than a desire for personal gain.

When the director of nurses at Cambridge City Hospital was fired in 1967, she employed similar language to dissuade her fellow nurses from striking on her behalf. Patricia Powers was terminated by the hospital “because she refused to rehire a subordinate nurse whom she had discharged for a disciplinary infraction.”[22] Noting that she was the mother of a 3-year-old daughter and the wife of a Cambridge police officer, the Boston Globe reported that Powers “said she will go to the meeting and ask them to think of the patients and not strike.”[23] By emphasizing her roles as a mother and as the wife of a public servant, the article underscores her portrayal as a selfless caregiver placing the needs of her patients above her own. The next year, when the same group of nurses voted to ask the Massachusetts Nurses Association to impose sanctions against the Cambridge City Hospital, they did so using the same rhetoric of concern for patient care and conditions. Speaking on behalf of her fellow nurses, Virginia Petralia stated that “[p]oor working conditions and apparent lack of interest by the city in improving conditions have continually frustrated the nurses in their attempts to upgrade nursing care for the patients, and the hospital’s attempts to recruit more nurses.”[24] By focusing on their capacity to adequately care for their patients rather than directly on their own economic wellbeing, nurses were able to push for reforms while remaining in the public eye as selfless caregivers whose only concern was for those they served.

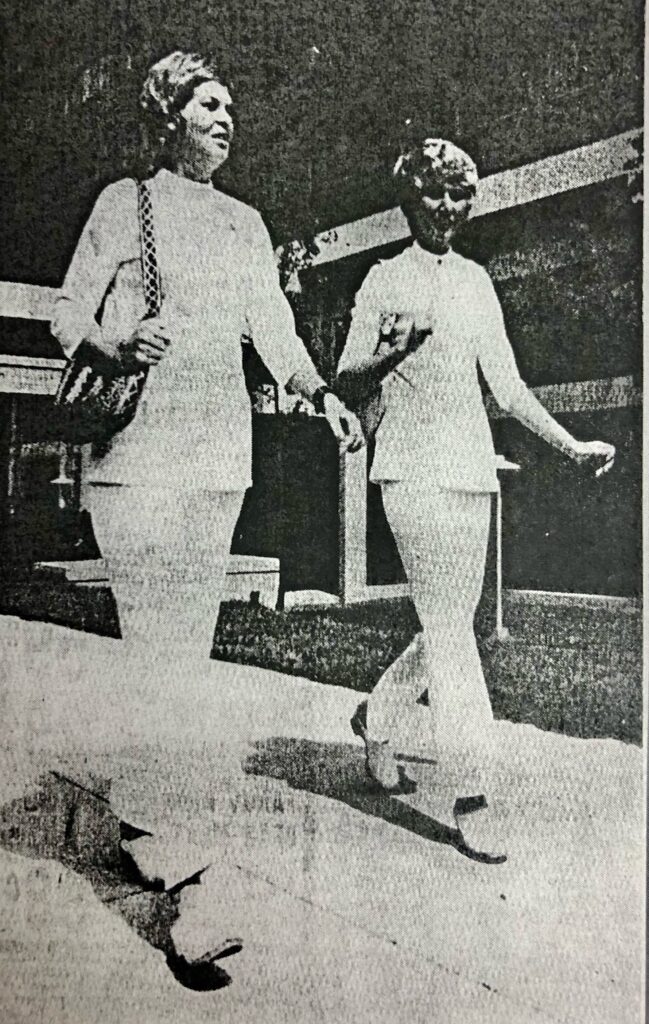

Amid the continuing push for nursing reform in the second half of the twentieth century, a trend emerged which highlighted both the rigors of the nursing profession and the extent to which nurses were still evaluated on their physical appearance and presentation. In 1970, the Boston Globe devoted nearly a full page to an article describing the new fashion at the Cambridge City Hospital: pantsuits. Noting that “[t]he nursing profession is a strenuous one, what with all the bending, lugging, kneeling, pushing and pulling. It is also, increasingly, a youthful one, and this has presented a problem for the fashion-conscious nurse in the mini uniform. The problem: how to be fashionable and still operate with comfort, efficiency and decorum in a busy hospital?”[25] The solution, it seems, was the introduction of pants into the wardrobes of nurses in the Intensive Care Unit (at press time, this was the only department whose head had approved the new uniform). The article includes reactions from a wide variety of doctors, nurses, and even patients, including Rosemary McDonald, head of the hospital’s ambulatory service:

I think pants are terrific. Mini skirts are terrible. Most of the younger girls like the idea of wearing pantsuits. Older nurses, of course, who have been nursing 20 or 30 years won’t make the switch. But our main concern is what the patients think – and the men say the most important thing is shape, anyway! They like seeing something new, and they like pants.[26]

Although the addition of pantsuits into the nurses’ wardrobe undoubtedly gave them more flexibility, comfort and coverage in their work, the shift in appearance called into question their femininity and presence as attractive and affable caregivers; by soliciting the opinions of male patients, nurses were able to show that their new work uniforms were both practical and appealing, and ultimately led to the adoption of pants for nurses hospital-wide.

As the Cambridge population expanded and aged over the twentieth century, the city’s nurses became even more vital; whether serving at hospitals, in homes with the Visiting Nurses Association, or abroad during wartime, Cambridge nurses were lauded as selfless and self-sacrificing caregivers who put the needs of their patients above their own economic concerns and even above their own health. This has never been more true than in the current era of COVID-19. In our final segment, we will explore the role of healthcare professionals and other essential workers over the past year to better understand their experiences on the frontlines of the coronavirus pandemic and their efforts to juggle paid and unpaid labor.

[1] “Fair in Aid of the Deaconess Hospital,” Cambridge Chronicle, October 26, 1901.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Doing Noble Work,” Cambridge Tribune, March 11, 1905.

[4] “Nurses Find Cupid in the Sick Room,” Cambridge Sentinel, December 2, 1911.

[5] “Voted Prettiest Girl,” Cambridge Sentinel, July 15, 1916.

[6] “Inspiring Parade for Liberty Loan,” Cambridge Chronicle, May 4, 1918.

[7] “Cambridge Women Alive to War Necessities,” Cambridge Sentinel, May 11, 1918.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, University of Michigan. https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-cambridge.html

[10] “Roll of Honor Growing Greater,” Cambridge Sentinel, October 5, 1918.

[11] “The Charlesgate Hospital,” Cambridge Sentinel, December 31, 1921.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “High Praise Given to the Good Work of Visiting Nurses,” Cambridge Tribune, March 12, 1932.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Watertown Girl Gets 2d Lieutenancy in Army Nursing Corps,” Boston Globe, July 26, 1941, p. 11; “Cambridge Nurse Awarded Air Medal,” Boston Globe, August 30, 1944, p. 14.

[16] “Gravely Ill Cambridge Nurse’s Only Concern is Brave Combat Boys,” Boston Globe, October 30, 1945, p. 1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “City Mgr. Proposes, City Council Ponders,” Cambridge Sentinel, August 3, 1946.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Nurses’ Pay Charges Aired in Cambridge,” Boston Globe, February 7, 1957, p. 11.

[22] “‘Politics’ Denied in Nurse Ouster,” Boston Globe, March 9, 1967, p. 6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “Cambridge Nurses Ask Sanctions,” Boston Globe, June 8, 1968, p. 9.

[25] “These Nurses Fashionable and Comfortable as Well,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1970.

[26] Ibid.