There’s also a tree made of wood: Edward Everett and the Washington Elm

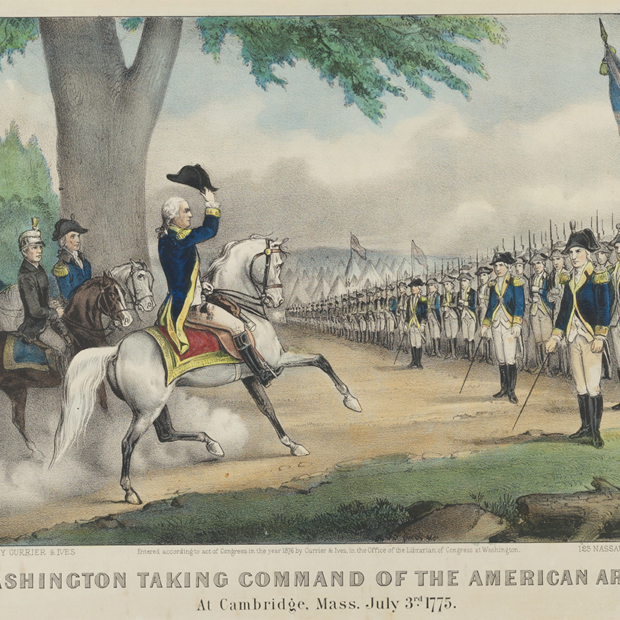

Above image” “Washington Taking Command of the American Army,” an 1876 print by Currier and Ives. (Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By Sean Alan Cleary

After publication of an article on the Washington Elm, History Cambridge received feedback that there are other, more complex and less celebratory aspects to the tree’s legacy. As part of our efforts to provide a more complete perspective on our city’s past, we are pleased to have writer and historian Sean Alan Cleary share his research on the Elm’s use as a symbol in Cambridge and beyond.

The Washington Elm you see today in Cambridge Common is not actually the Washington Elm. If you’ve walked by the hulking granite marker that reads “Under this tree Washington first took command of the American Army, July 3rd, 1775” and looked up at the stout but fairly youngish-looking Elm tree and had a feeling of disconnect, you’d be forgiven. When the Cambridge Historical Commission transferred this marker to its place under this tree in 1976, it acknowledged that the “Washington Elm” was not just a tree, but instead a representation of an event – Washington’s assumption of command. The tree itself, you might say, can change, but the idea stays the same. The question becomes what is being remembered about that event out of all the events that took place around Cambridge in 1775, and for what reason?

There are a lot of ways we can approach the Washington Elm’s memorialization as a representation of a historical set of values. But I’ll focus here on examining it through three questions: What was the existing tradition of symbols like it that the Elm spoke to when it was created as a marker? What was the purpose of the Elm as a symbol, and who created it? For what reason and how was that symbol sustained in its representation through markers and memorials?

In creating the Washington Elm as a historical representation, the creators of the Elm myth seem to have tapped into two traditions of monumental trees – that of the English tradition of trees as places of compact and the traditions of the Wampanoag and other indigenous groups who saw monumental trees as places of meeting, and in particular places of listening to communities. Somerset’s former Council Oak, felled in a 2021 storm, can be seen as the coming together of these two traditions: a place once held as the ceremonial seat of the Massasoit (the leader of leaders) to listen to the concerns of the local Wampanoag communities, and later a place of colonial importance and meeting as the traditional center of the old town.

Neighboring Dighton has a similar oak, and although in both cases part of the history of the trees claimed by the white settler community was used to legitimize the process of colonization – the Dighton oak has a marker that claims it was the place where the land-sale agreement was agreed upon by the Wampanoag peoples – the trees’ importance exists in Wampanoag tradition as well. They are remembrances of an ancient system of agreement and governance that once existed and, though ignored largely by the U.S. government, still exists.

The most immediate precedent for the symbolic importance of the Washington Elm is Boston’s own Liberty Tree, a monumental American Elm whose shade hosted the meetings of the Sons of Liberty from the 1760s onward. The tree was of such importance to the Bostonians involved in the revolution that the British loyalist Nathaniel Coffin hacked it down during the siege of Boston in the summer of 1775. It was seen as an act of war, a blow to the spirit of the Revolution. Thomas Paine memorialized the tree in a poem written in July of that year, and claimed that under it “one spirit” was formed. That oneness, the desire for an agreement among the different colonies and their peoples in the Revolution, is important to remember, especially in relation to the Washington Elm.

Our elm, then, the Washington Elm. It first shows up in the historical record in an 1826 speech by Edward Everett marking the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In 1826, Everett was already well known as an orator and an academic, but was just starting out as a politician – he’d been swept into Congress the year prior largely because of his popularity as a speaker and a respected critic of American letters.

Until that point, the Revolution itself lived in the memories of those who experienced it. But the generation that had created the country was aging – unbeknownst to him, as Everette spoke on July 4, 1826, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams lay dying, and that meant a fundament question of identity needed to be asked.

Everett’s speech addressed important things on people’s minds as they sat in First Church: What should be remembered about the Revolution, and who are we as Americans in 1826? This speech and its role in creating the Washington Elm is largely hidden from most memorials – there’s no information about it in the historical markers, and Everett as the booster of the Elm as a symbol is rarely credited. That might be because Everett’s answering of those questions was animated in exaggerated, racialized depictions of those he thought shouldn’t be included in this new America.

Midway through his speech, he reels in his audience with lurid detail – a style of sermonizing in the New England tradition of Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

“We cannot admit to this new American nation,” he calls to his audience in the church, “the New Hollander [i.e., the Aboriginal Australian], making a nauseous meal from the worms which he extracts from a piece of rotten wood; or the African cutting out the under jaw of his captive to be strung on a wire, as a trophy of victory, while the mangled wretch is left to bleed to death, on the field of battle.” They are two images of racialized otherness (i.e., racism) that echo across the literature of American white supremacy: The racialized other is depicted as disgusting and savagely violent. He goes on to say that Washington’s assumption of command “beneath the venerable elm, which still shades the southwestern corner of the common” should remind his audience of the agreement, the union (or Union) made in that moment.

But what then was that Union? If we see the tree as a symbol of compact, who was that compact between? Everett had already answered; in his first speech to congress he said that though he was from Massachusetts, a non-slave state at the time, he vowed that though “my habits and education are very unmilitary: there is no cause in which I would sooner buckle a knapsack to my back and put a musket to my shoulder” if his fellow (white) Americans in the South were ever faced with a revolt of enslaved Africans. The two speeches taken together paint a clearer picture of Everett’s understanding of what the tree, and what it memorialized in Washington’s assumption of command, meant to him and later the brand of Unionism he promoted in the lead-up to the American Civil War. For Everett, and for many trying to toe the line between secessionist and abolitionist politics, the Union that was worth preserving was the union of white Northerners and Southerners, a union epitomized by the Virginian plantation-holding Washington commanding an army of yeoman farmers and townspeople from across New England (tellingly, one of Washington’s first orders was to expel all the nonwhite soldiers in his ranks). And while often these Unionists were at pains to explain their distaste for the institution of slavery, they were equally clear in their willingness to abandon that moral stance if it meant preserving the Union.

Although there’s a lot to say about the life of that moment of Union, it’s important to note that Everett’s influence on early Cambridge, and especially the symbols the city still uses – Everett designed the city’s seal (featuring prominently the Washington Elm) and its motto – has been largely ignored in its history. Not a single monument to the man exists in Cambridge. No blue oval marker tells his story. It’s also important to note that Everett’s voice was not the only one in Cambridge and Boston. This was, after all, an abolitionist town in many respects. When Everett was set to speak at another Fourth of July celebration, this time in Dorchester in 1855, the local abolitionists distributed a pamphlet urging citizens to boycott the event. Because of his persistent pro-slavery stance, “Massachusetts has placed her condemnation on him,” the pamphlet said. “Remember what EDWARD EVERETT has said and done!”

And that of course is the question history asks Cantabrigians today. The Washington Elm, in its relation to Everett, might be called a dead metaphor. It’s invoked, but those who invoke it largely have no clue of its origins and meaning. It memorializes the importance of Washington’s assumption of command, but what is that importance if not Everett’s stated and explicitly racist importance?

Part of the problem is the incoherence of the public history presentation of the Washington Elm. It’s not just fallacious to have a marker that lies; the multitude of monuments provide little in the way of context or elucidation of the various historical moments they examine and memorialize. Every time I pass the elm or stand by it as I watch my son’s soccer practice, I think about that 1855 pamphlet and it’s plea. I wonder, are we remembering?