The Hooper-Lee-Nichols House has a haunted history

By Beth Folsom, 2022

This month, the Cambridge Historical Commission organized Cambridge Open Archives, online events that let six of the city’s history organizations share items from their collections. In the lead-up to Halloween, the theme was “Morbid, Morose and Macabre,” and each participant highlighted appropriately spooky elements of their holdings. History Cambridge shared several of the ghost stories associated with its headquarters, the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House at 159 Brattle St., West Cambridge.

Now the second-oldest in Cambridge, the Hooper-Lee-Nichols house was built for prominent physician Richard Hooper. He died in 1691, leaving his widow Elizabeth Hooper with severe financial troubles. She was forced to take in boarders and convert her home into a tavern. We don’t have details about the goings-on at the establishment, but it soon earned a reputation for being “a filthy, embarrassing business.”

Elizabeth’s body was found wrapped in a sheet inside the house, which lodgers and tavern-goers had collectively wrecked, in 1701. The mysterious circumstances surrounding her death have only added to the macabre history of the home. Was she murdered, or did she succumb to an unknown illness? Elizabeth’s troubled spirit is said to walk the halls still, hindered by her tragic end. Some say they have seen her gliding across the floor in the same white sheet her corpse was found in.

In 1850, the house was rented to George and Susan Nichols. That year, the Nichols were celebrating the Fourth of July at their new residence, showcasing the remodeling they had done, when their young granddaughter stepped on lit fireworks. The open wound became infected, and she died shortly after. From then on, the spirit of the Nichols granddaughter has been said to haunt the house, responsible for objects moving from one place to the other without explanation. Some have also reported hearing the sound of weeping, which they attribute to the young girl’s spirit.

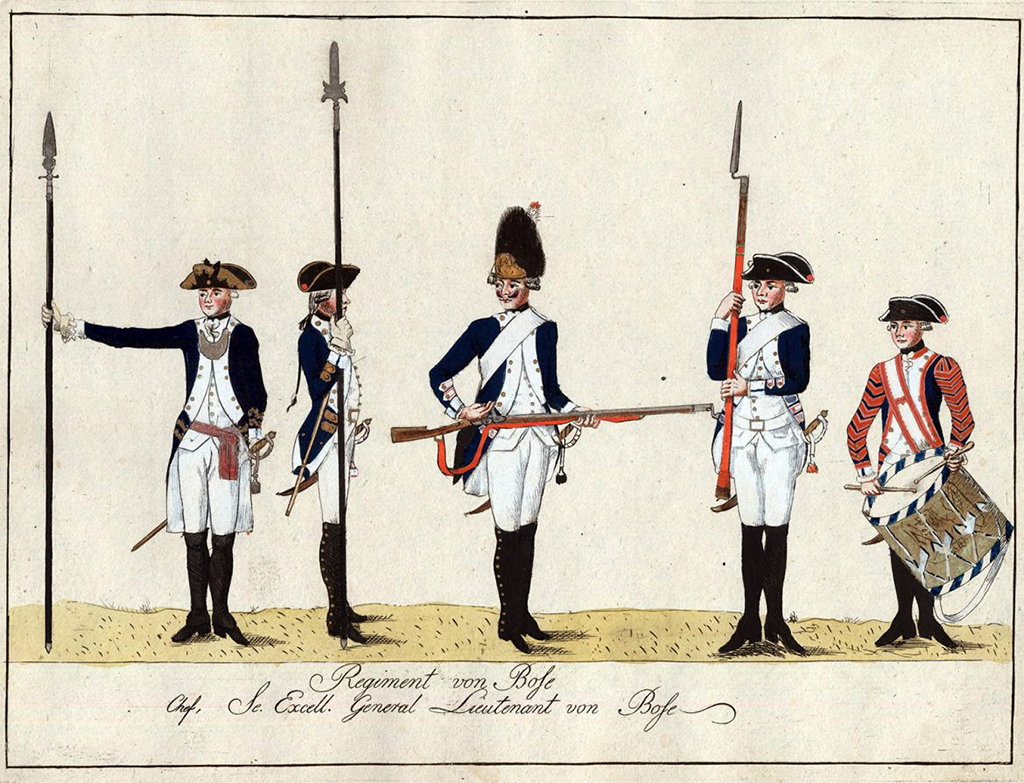

The most widely known associated ghost story is of a group of five Hessian soldiers playing cards in the Chandler Room at the back of the house. Americans used “Hessian” as a catch-all term for all the Germans who fought on the British side during the American Revolution, since 65 percent came from the German states of Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau. Approximately 30,000 Germans fought in the Revolution, making up around a quarter of the British land forces, and were known for their military skill and discipline.

Most Americans (then and now) think the Hessians were mercenaries, but they were actually auxiliaries. Whereas mercenaries were individual soldiers who offered their services to a foreign government for money, auxiliaries were hired out by their own government, to whom they remained in service, fighting under their own commanding officers and in their own regiments.

Britain’s use of Hessian troops is listed as one of the 27 grievances against King George III in the Declaration of Independence. American colonists and British soldiers largely distrusted the Hessian soldiers, stereotyping them as crude, barbaric foreigners unfamiliar with British customs or the English language. Even Tory supporters were often reluctant to house and quarter Hessian troops alongside their British counterparts because of these perceived cultural differences.

Throughout the war, reports of plundering by Hessians were said to have galvanized neutral colonists to join the Revolutionary side. George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River at Christmas in 1776 was intended as a surprise attack on the Hessian army. According to an old myth, Washington met light resistance at the Battle of Trenton because the town’s Hessian defenders had been up late the night before celebrating Christmas. Although not based in fact, this myth drew upon the stereotype of Germans as incompetent drunkards. The resulting Battle of Trenton ended with 1,000 Hessians captured and paraded through the streets of Philadelphia to raise American morale; anger at their presence helped the Continental Army recruit soldiers.

Perhaps the best-known Hessian in popular culture comes from Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In this novel, set in Westchester County, New York, in 1790, the mysterious sights and sounds of the village are attributed to the ghost of a Hessian soldier whose head was separated from his body, and who rides a spirit horse by night in a quest to find it. In its various adaptations, the story has portrayed the Hessian as a savage ghost, unleashing cruel retribution on the living in return for his dismemberment.

As for the haunting of the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House, rumors existed from the time of the Revolution that a group of Hessians was encamped on the property and that at least several of them died and/or were buried there. There is no evidence to suggest this was the case, although it’s possible – Hessian troops were quartered on Brattle Street. The rumor of Hessian bodies on the property goes back to the 1780s, but it was not until the renovations and addition of the Chandler Room in 1915 that sightings began of a group of five Hessian soldiers playing cards there.

It is worth noting that the resurgence of this story – and the addition of the ghostly figures – coincides with the start of World War I and the emergence of Germany as a military powerhouse in the early 20th century. Just as they had during the Revolutionary Era, many Cantabrigians viewed their neighbors of German heritage with suspicion, questioning their loyalty to the United States. Nearly a century and a half after the Hessians lived and died in Cambridge, the reappearance of this ghost story into the zeitgeist tells us that not much had changed in attitudes toward this foreign military power.

More than that, it reminds us that ghost stories and tales of hauntings reveal what – and whom – we fear most.