The ‘Hiker’ statue is monumental miseducation about Filipinos in Cambridge and 51 other cities

By Jeromel Dela Rosa Lara, 2022

There may not be many Filipinos in Cambridge – as a Harvard student, I am one of the few – but it seems that the Philippines mattered enough to the community to place a monument about my country of birth on Arsenal Square, at Garden Street and Concord Avenue in Neighborhood 9.

I pass by it as I walk from my dorm in the Radcliffe Quadrangle to my classes in Harvard Yard: “The Hiker,” an 18-foot-5 monument of a soldier clutching his rifle atop a pedestal bearing a bronze marker in the shape of a cross. The top of the cross says “Cuba,” then “Porto-Rico” on the right, “U.S.A.” on the bottom and “Philippine Islands” on the left. At the center is a circle with the inscription “Spanish War Veterans 1898-1902.”

Within the circle is a sculpted relief depicting a barefooted woman wearing a flowing, sleeveless dress. A stereotyped portrayal of an indigenous woman, she is kneeling with her arms outstretched, pointing downward in either direction. Her back faces the viewer. Her hands are open. Flanking the woman are armed white men in military uniforms, standing straight and facing each other. The man on the left wears an infantry uniform and holds a rifle. The man on the right wears a Navy uniform and holds a saber. Behind the men is a battleship at sea.

I was not expecting to find this Filipino American history connection in Cambridge, of all places. The history that this monument depicts is a deliberate “Miseducation of the Filipino,” to quote the title of an essay by Filipino postcolonial thinker Renato Constantino. Given the lack of education on the extent of America’s 48-year colonial rule over the Philippines, this is to be expected.

Because of this, I did a research project for one of my classes about the “Hiker,” including a comprehensive, multimedia StoryMap. There are no Confederate monuments in Cambridge, but there is this monument that Harvard students and Cantabrigians pass by that explicitly glorifies American (white) supremacy over the Philippines. Similar to the well-visited John Harvard Statue, “The Hiker” is a “statue of three lies.”

From the plaque, it would appear that the Spanish War was fought from 1898 to 1902, though the Spanish-American War was fought only from April to December 1898. What this monument – and much U.S. education curriculum – does not mention is the Philippine-American War from 1898 to 1902.

The depiction of the indigenous woman kneeling to the white armed men disregards that there was an active resistance against U.S. white supremacy. America had a hard time subjugating the Philippines, which it bought for $20 million from Spain at the end of the Spanish War in 1898. American had to send in its best generals, the “Indian fighters” who, Foreign Policy in Focus said, “brought to the archipelago the genocidal mentality that accompanied their warfare against Native Americans in the American West.” And they fought for four grueling years.

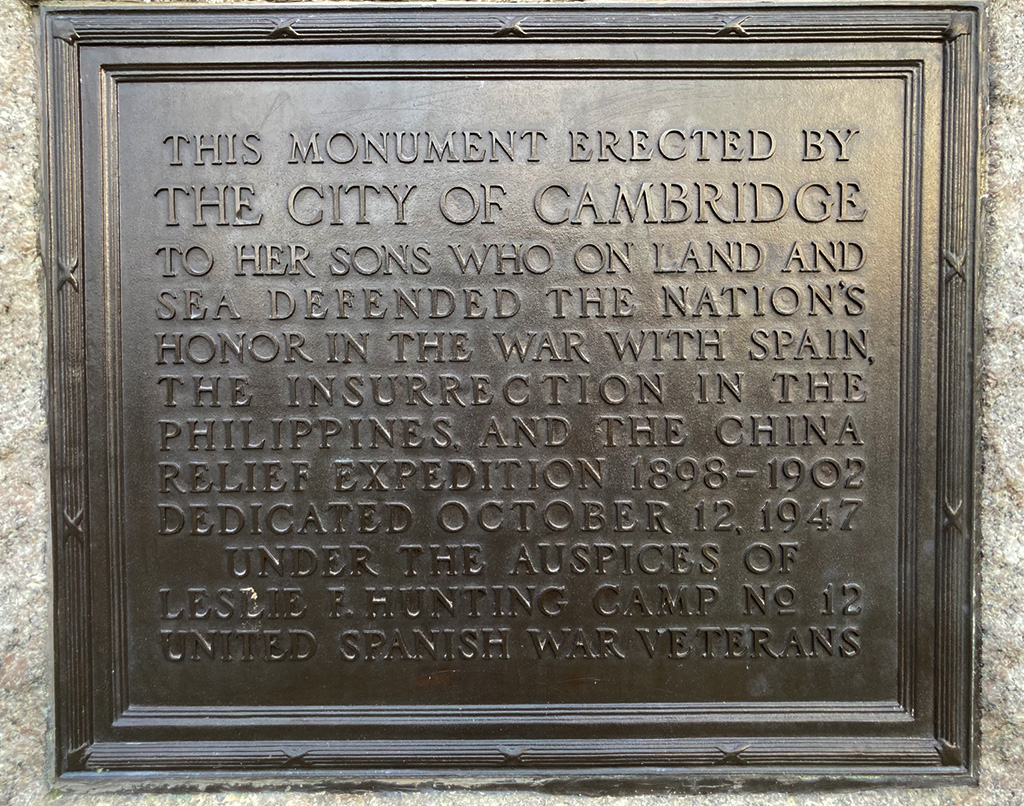

The back of “The Hiker” has another plaque explaining its erection to celebrate the Cantabrigian soldiers who fought in this war that “defended the nation’s honor.” In my StoryMap, I include well-documented accounts of U.S. soldiers burning down villages, multiple instances of Filipinos referred to as “n—rs” and “g—ks,” the first use by the U.S. military of what would become known as waterboarding and military top brass justifying all of this because the Filipinos “are not civilized.” About 200,000 Filipino civilians died in the targeted violence. Black soldiers deployed in the Philippines condemned these state-sanctioned acts of racial violence perpetrated by their white comrades and generals. Some defected to fight with the Filipinos.

This Filipino American history remains unspoken in the mainstream, even with the national consciousness we are seeing today on systemic racism and Asian American experience.

Yet it is not as though American colonial rule over the Philippines was insignificant. “The Hiker” is “one of the most replicated statues in the country,” according to Savannah (Georgia) College of Art and Design professor Christine Neal, who found 52 versions of it across America. The one in Cambridge was unveiled Oct. 12, 1947, with as many as 3,000 people in attendance, the Cambridge Chronicle reported.

I hope this monument can become a space to engage with this history. In cities such as San Francisco, Filipino American community members have convinced officials to add a marker to tell this underemphasized story. To not is a monumental miseducation. This is not new in America, but Cambridge has an opportunity to do better.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.