Smallpox, cholera, influenza around Cambridge: How the region endured pandemics of the past

By Martha Henry

April 2020

Reproduced from cambridgeday.com with permission

We’re weeks into the Covid-19 pandemic, most of us stuck at home, trying to work, educate children or, when that all seems futile, just clicking “next episode” on whatever escapist show we’re binging on Netflix. Our coronavirus, social-distancing spring seems unprecedented. But it isn’t.

New England has been coping with epidemics since the arrival of the first settlers, who brought all the Old World diseases with them to the New World and set off horrendous epidemics among Native Americans.

In colonial America, our counterparts dealt with deadly disease regularly. Epidemics were expected; they occurred every couple of years. The good people of Boston, Cambridge and surrounding towns survived outbreaks of smallpox, diphtheria, yellow fever, cholera, polio and influenza. Here is some of that story.

The 1721 smallpox pandemic

In 18th century New England, smallpox was the most dreaded disease.

For colonists of European descent, mortality from smallpox was about 30 percent. For Native Americans, with no natural immunity to a virus their bodies had never encountered, mortality was closer to 90 percent.

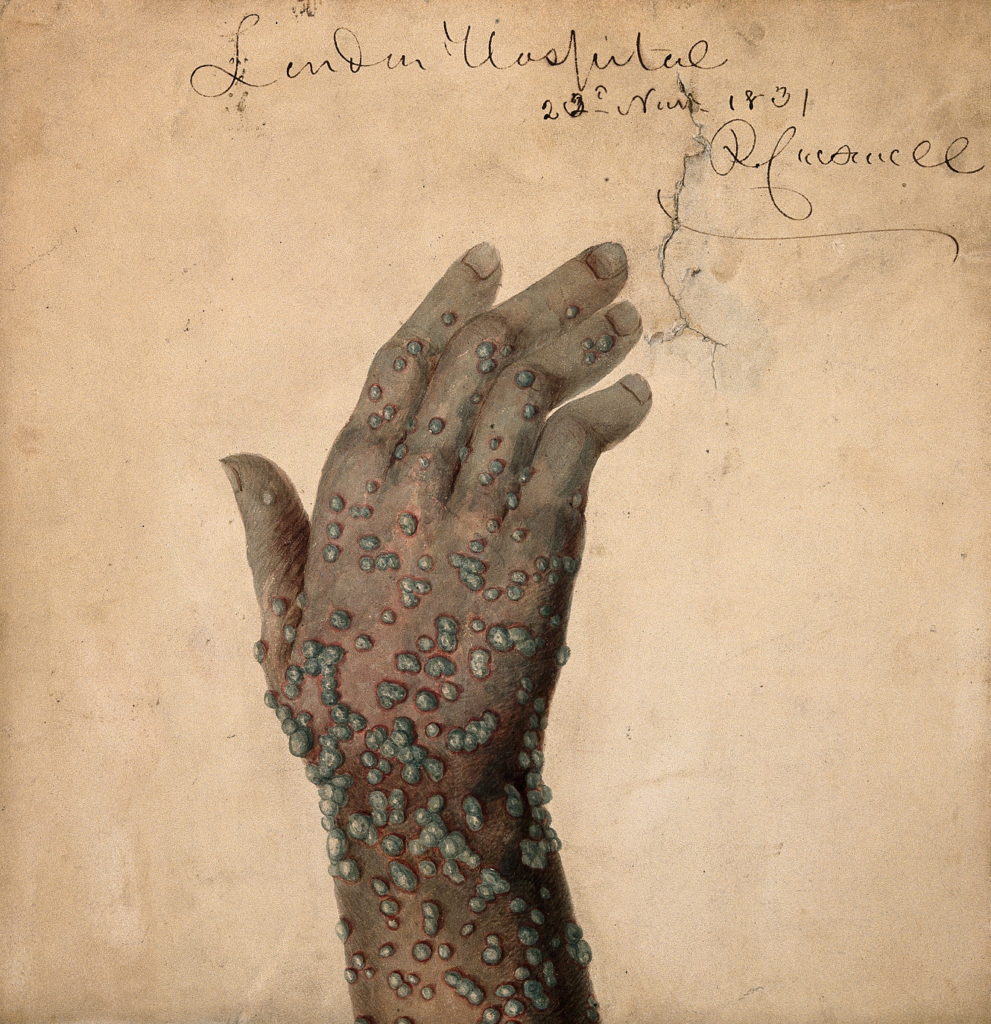

Smallpox spread by face-to-face contact, or less often by contact with contaminated clothes and bedding. The disease’s ghastly symptoms started with high fever, head and body aches, and vomiting, after which red spots appeared in the mouth and on the tongue. The spots became sores which then broke open, so that with every breath, the sufferer spread virus. Next, a rash began on the face and spread over the entire body. The skin sores filled with a thick, opaque fluid. The sores became pustules, firm to the touch. A few days later, the pustules crusted over to form scabs, which fell off in a few days to a week. A person with smallpox remained contagious until all scabs were gone. There was no effective treatment for the disease.

Survivors of severe cases were left with pockmarked faces and disfiguring body scars that lasted a lifetime. Though smallpox was a horrible disease, those who recovered enjoyed a lifelong immunity.

In spring 1721, smallpox arrived in Boston via a sick sailor on a ship from England. Cases quickly spread. To escape infection, the General Court moved from Boston to Cambridge that summer. By fall, Cambridge had its own cases.

Cotton Mather

You may know Cotton Mather as the fiery Puritan minister who helped prosecute the accused during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-1693. Less well known is his role in introducing inoculation to the colonies.

Inoculation was the practice of inducing a mild case of smallpox intentionally to protect a person from contracting a life-threatening case. Though the practice was used in China, India, Turkey and Africa, in the 1700s, it was just beginning to be adopted in England, due largely to Lady Mary Montague, who had observed the effectiveness of smallpox inoculation in Turkey when her husband had served as the British ambassador.

Mather first learned of about inoculation from his African slave Onesimus. The idea was supported by letters published from Emmanuel Timoni, the physician to Britain’s ambassador to Turkey.

During the Boston outbreak, Mather advocated publicly for inoculation. He enlisted the help of Zabdiel Boylston, a local physician. In June 1721, Boylston inoculated two slaves and his own son by applying pus from a smallpox sore to a small wound on the subjects’ arms.

Boylston later published the story of his work in “An Historical Account of the Small-pox Inoculated in New England, Upon All Sorts of Persons, Whites, Blacks, and of All Ages and Constitutions.” Out of the 287 people Boylston inoculated in 1721, only 2 percent died. The fatality rate of the naturally occurring smallpox that year was about 15 percent.

Reaction

Mather’s advocacy for inoculation was hugely unpopular. He and Boylston received threats of death and damnation. Both men had gunpowder grenades thrown through their house windows. Heated debates about inoculation played out in Boston’s papers.

In “The Awful Judgements of God upon the Land: Smallpox in Colonial Cambridge, Massachusetts,” (New England Quarterly, 2001), John Burton wrote, “Sickness was normally attributed to an act of God, and because the colonists had little understanding of either the transmission or the nature of most illnesses, the community knew of few actions that it could take to prevent outbreaks.”

In the Puritan New England of 1721, smallpox, and everything else, was attributed to god’s will. An outbreak of disease was seen by most as divine punishment. Any effort to interfere with god’s will was seen as heresy.

A lot of local physicians were also clergymen and opposed to inoculation, though in the waning months of 1721, other ministers joined Mather and got inoculated themselves. The practice eventually spread to other colonies.

After 1721

Smallpox outbreaks continued on and off for the rest of the 18th century, yet belief in the effectiveness of inoculation was growing. Between outbreaks, it became common for upper-class parents to take their children to an inoculation hospital, where a healthy person could undergo induced smallpox and remain in quarantine for several weeks while recovering from (hopefully) a mild case of the virus. By the 1790s, inoculation was widely accepted.

Edward Jenner, an English physician who practiced in a rural area with lots of cows, noticed that milkmaids seldom got smallpox. In 1796, he discovered that inoculation with cowpox virus was a much safer method that didn’t require a quarantine period. Cowpox doesn’t cause disease in humans but provides crossover immunity to the smallpox virus. Jenner’s discovery was the first example of a vaccination. Vacca is the Latin word for cow.

By the early 19th century, smallpox vaccination was common in Europe, though doctors weren’t at all sure how it worked. By the end of the century, germ theory – the idea that some diseases are caused by microorganisms known as pathogens or germs that can lead to disease – had gained widespread acceptance in the medical community.

In 1800, Benjamin Waterhouse, a professor at Harvard Medical School, became the first to perform smallpox vaccination in the United States. In 1827, Boston became the first city to require all children entering public schools to show proof of vaccination. In the 1850s, Massachusetts became the first state to do the same. The requirement was put in place after the school attendance law caused a sharp rise in the number of children attending public schools, thus increasing the risk of a new smallpox outbreak.

Though the disease was preventable, in the 20th century smallpox continued to take a huge toll and was estimated to have killed up to 300 million people. In 1959, to address this preventable tragedy, the World Health Organization announced a global campaign to eradicate smallpox.

After years of immunization efforts, on May 8, 1980, the WHO declared victory. Deadly smallpox outbreaks, like the one that swept through Boston in 1721, were over. Smallpox became the first and only infectious disease to have been eradicated from the human population, though small samples of the virus still exist in U.S. laboratories and in other countries, including Russia and likely North Korea.

The 1849 cholera pandemic

In 19th century New England, cholera became the most feared disease. Though it was an old plague in Asia, it didn’t arrive in Europe until the 1800s. Cholera made its debut in New England in the 1830s, having first journeyed from India to England.

“You can associate it with more ships going faster into more different places, so you can say cholera is an early symptom of globalization in terms of its spread,” said Charles Rosenberg, professor of the history of science emeritus at Harvard and author of “The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866.”

People contract cholera after drinking water or eating food contaminated with human feces that contains the cholera bacteria, though in 1849, the cause was not yet clear.

Symptoms, which start a few hours to a few days after exposure, include profuse watery diarrhea, vomiting, rapid heart rate, low blood pressure and extreme thirst. Those infected can also develop acute renal failure, severe electrolyte imbalances and coma. If left untreated, dehydration can lead to death in hours. Because a person’s skin may turn bluish-gray from extreme loss of fluids, cholera has been called the Blue Death.

Because the disease thrives in the absence of sewer systems, cholera overwhelmingly affects the poor, especially in big port cities. In 1848, a ship carrying Italian immigrants with cholera arrived in New York City. Within months, the disease spread to Boston.

In 1849, Boston was growing quickly, with a population of more than 100,000, including thousands of recent immigrants who had fled the Irish potato famine. Irish immigrants were especially hard hit by Boston’s cholera outbreak, accounting for more than 500 of the 611 recorded deaths in the city. Prosperous sections of Boston, with access to clean water and proper sanitation, remained relatively untouched.

Boston’s cases were clustered in tenements occupied predominantly by Irish immigrants in the Fort Hill neighborhood, site of today’s Financial District.

The Asiatic Cholera Report, Boston 1849, describes the conditions found by a Visiting Committee:

We allude to the very wretched, dirty and unhealthy condition of a great number of the dwelling houses occupied by the Irish population …

The great mass of them … have but one sink, opening into a contracted and ill constructed drain, or, as is frequently the case, into a passage way or street, and but one privy, usually a mass of pollution, for all the inhabitants, sometimes amounting to a hundred …

Few of the cellars have drains or privies. Some of them are divided off into one or more rooms, into which hardly a ray of light, or breath of air passes, and where notwithstanding, families consisting of several persons reside. How the lamp of life, under such circumstances, holds out to burn, even for a day, is, perhaps, as great a wonder as that such a state of things should, in this community, be suffered to exist.

The Asiatic Cholera Report called for reforms: that every house should contain sufficient sinks, drains and privies and that owners should be compelled to make changes under threat of fine.

Boston’s 1849 epidemic ran its course from June through November.

After 1849

In 1854, John Snow, an English physician, tried to determine the source of a cholera outbreak in the Soho section of London. By carefully mapping out who had been infected and where they lived, he was able to identify the source of the outbreak as the public water pump on Broad Street. His research convinced the local council to disable the pump, an action credited with ending the outbreak. Snow’s work inspired the adoption of significant changes to London’s water and waste systems, which led to similar changes in cities around the world.

After another cholera outbreak in 1866, Boston began to plan and build a modern sewerage system to protect residents from disease. The sanitation system, up and running by 1884, helped curtail the spread of waterborne pathogens in the city.

In the 19th century, physicians had no effective treatment for cholera, and the fatality rate was about 50 percent. In 1909, Leonard Rogers, a British physician working in India, found he could reduce mortality to 15 percent by using oral rehydration therapy – replacing lost fluids with slightly sweet and salty solutions.

According to the WHO, there are still an estimated 1 million to 4 million cholera cases worldwide every year, with 21,000 to 143,000 deaths, mainly in countries that still lack clean water and proper sanitation. Regions with an ongoing risk include Africa, Southeast Asia and Hispaniola.

The 1918 influenza pandemic

Your grandmother may have remembered the great 1918 Influenza Pandemic, which occurred as World War I was coming to a close. In Boston, cases exploded in the fall, as they did in Freetown in Sierra Leone, and Brest in northwest France, all port cities where troops and supplies were on the move, spreading the virus.

In Boston, the Receiving Ship tied up in the harbor served as a point of induction for new recruits. On Aug. 28, 1918, sailors aboard the ship were getting sick with unusually severe cases of influenza. By mid-September, the virus had spread to nearly 21,000 sailors in the Boston area. At Camp Devens, an Army installation of 50,000 men 45 miles northwest of Boston, medical officers were overwhelmed by the onslaught of cases.

On Sept. 11, Babe Ruth led the Red Sox to a World Series victory as the first civilian cases were reported. By Sept. 16, there were hundreds of cases in the city, causing overcrowding in City Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Six cases appeared at the Charles Street jail. Many Bostonians were dealing with symptoms at home.

On this side of the river, Cambridge quickly had influenza cases of its own. By mid-September, 221 trainees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s naval aviation school were struck with the grippe, as influenza was called (because, like the French verb gripper, it gripped or seized quickly those who became infected).

Harvard tried to keep cases under control by suspending classes with 50 or more students and quarantining the 1,450 men who were part of the Student Army Training Corps, many of whom were due to be inducted in October. The men were monitored daily by medical students. Anyone presenting signs of infection was sent to the campus isolation ward.

According to the University of Michigan’s Influenza Encyclopedia, Boston’s health commissioner called on the public to avoid crowds and remain at home. As the month progressed, cases mounted, with dozens of deaths each day due to influenza and pneumonia.

To make matters worse, there was a shortage of medical personnel to treat the sick. Many of the state’s doctors and nurses were overseas, attending to the troops. In the Boston area, hospitals were unprepared and understaffed.

On Sept. 24, Gov. Samuel McCall asked every able-bodied person with medical training to join efforts to fight the epidemic. Officials in state and local government discussed whether to close schools and businesses. In Cambridge, 3,400 public school students were reported ill, almost a quarter of the total enrollment.

“The tensions between the economic aspects and the public health aspects were already clearly evident back then,” said Dr. Scott Podolsky, professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the Countway Medical Library.

On Sept. 25, Boston closed schools. Cambridge quickly did the same.

On Sept. 26, Boston closed theaters, movie houses and dance halls, and prohibited public gatherings. Churches were allowed to stay open with reduced services.

On Sept. 29, Cambridge, facing a shortage of hospital beds, set up a temporary emergency hospital at a local school. Patients were moved there that evening. There were no physicians or nurses available, so patients were tended by volunteers, which included teachers, housewives and off-duty firemen. Physicians soon arrived from other states. Almost immediately, the overflow hospital was itself overflowing. Tents were set up in the schoolyard to treat the growing number of patients.

Though seasonal influenza takes its toll every year, the 1918 virus – spread by coughs, sneezes and contact with infected surfaces – was especially deadly. There was no flu vaccine to stop the spread; there were no antibiotics to treated influenza-related pneumonia. “There were certainly no ventilators, and oxygen therapy was far more primitive,” Podolsky said.

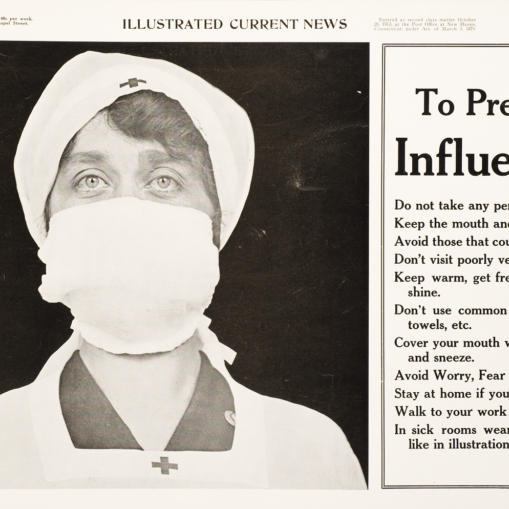

In areas of the United States, citizens were urged to wear cloth masks. Surfaces in hospitals and trains were wiped with disinfectants. And still the virus spread.

Hospitals couldn’t keep up with the rising number of very sick patients. There was a shortage of beds. Doctors and nurses were overwhelmed. At the Peter Brent Brigham Hospital, 32 nurses got sick with influenza and were unable to work.

In early October, the Massachusetts Department of Health made influenza a reportable disease – required by law to be reported to government authorities – so case numbers could be easily tracked.

On Oct. 5, the Cambridge Board of Health voted to ban church services and to close all pool halls, bowling alleys and ice cream shops. Attendance at funerals was limited to immediate family.

By the middle of October, Boston had more than 3,500 deaths from influenza or pneumonia since the start of the epidemic, though the daily death count was beginning to slow.

On Oct. 19, Boston allowed bars, poolrooms, bowling alleys, theaters and movie houses to reopen. Children returned to school the following Monday.

On Oct. 23, Cambridge physicians reported only 31 new cases. Cambridge schools reopened Oct. 28. The school hospital closed Nov. 6.

While supporting the lessening of restrictions, state officials warned that influenza would continue to circulate to some extent through the following winter. In November, a slight rise in influenza cases was reported, likely due to the crowds that gathered to celebrate the armistice with Germany on Nov. 11.

Influenza continued to circulate through the early months of 1919. After a rise in new cases in December 1918, Cambridge school officials extended the Christmas break into mid-January.

The worst scourge

Looking back at the deaths of 1918, health officials wrote in the Cambridge Annual Report, “This year cannot be compared in totals to any previous year on account of the pandemic of Influenza, one of the worst scourges the medical world has known.” By the end of February 1919, Cambridge had lost 688 people to influenza and pneumonia, from an approximate population of 109,000.

In the fall of 1918, Boston lost 4,794 people to influenza and pneumonia, making it one of the worst hit cities in the United States.

Though estimates vary, according to the Centers for Disease Control, about 500 million people, a third of the world’s population, was infected with influenza during the 1918-1919 pandemic. There were about 675,000 deaths in the United States and at least 50 million worldwide. Though influenza outbreaks are usually most fatal for infants and the elderly, the 1918-1919 influenza was most fatal to 20- to 40-year-olds.

In the 1940s, the U.S. military developed the first approved vaccines for influenza.

Epidemic as reflection

Covid-19 is playing out like past pandemics, though with globalization and the Internet, the virus and news of it are spreading at unprecedented speed. We can see a map of the world on our screens, and as of mid-April, an upward curve of deaths and new infections. For all our advances in medicine and technology, the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV is, for the moment, winning.

“It’s very humbling, frankly,” Podolsky said. As a medical doctor and medical historian, he sees how our current epidemic reveals the obvious pressures points in society, as well as the need for good preparation and leadership, and the concerns when they’re not there.

Harvard historian Rosenberg sees the big picture. “When you think about the disease, you can’t just think about it as a biological thing and divorce it from the cultural, institutional and political context in which it’s worked out, performed, acted out,” Rosenberg said. How we, as a society, deal with epidemics tells us a lot about ourselves.

Martha Henry writes about recycling, consumption and other topics for Cambridge Day. She blogs at Persistent Self.