History of poorhouses reflects changing attitudes toward those on the margins of society

By Heli Meltsner, 2024

This year, as part of its exploration of North Cambridge, History Cambridge highlights the ways in which the neighborhood has historically been home to industries and institutions Cantabrigians needed but wanted to push to the edges of the city’s boundaries. Slaughterhouses, tanneries and brickyards were all necessary industries, but those in the more densely populated (and, often, more wealthy) neighborhoods of the city deliberately located many of these facilities in the more sparsely populated and less-developed North Cambridge neighborhood so their noise and smells would bother fewer (and poorer) people. Institutions such as the city’s almshouse and poor farm were also here, nominally because there was available land, but also in an attempt to place the poor, aged and infirm in a location that was, for many Cantabrigians, “out of sight, out of mind.”

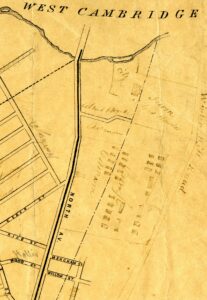

Cambridge bought its first two almshouses in 1779 in Harvard Square and in 1786 off North Massachusetts Avenue. It built the third in 1818 in Cambridgeport. Described as “large and well constructed in a retired and tranquil part of the village,” it burned in 1836. The city erected its fourth near the Charles River, but the property was sold in 1849 due to overcrowding and increasing land values. The city immediately bought a large site for the fifth poor farm at “Poverty Plain,” an extensive acreage in the extreme northwest corner of the city. When constructed, the massive building rose alone on its hilltop in a mixed agricultural and industrial area; now it is hidden in an early 20th century neighborhood developed on its fields.

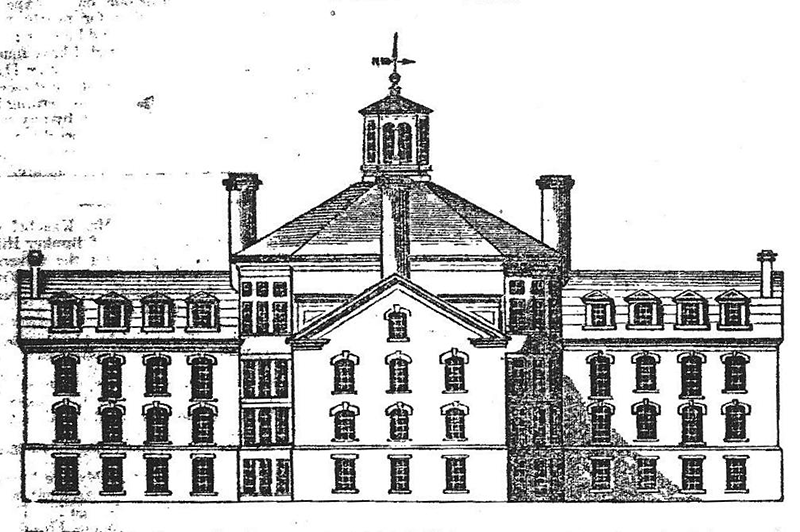

Although design competitions for municipal buildings were rare in the mid-19th century, the city held one for the almshouse. The winners were the team of the prolific local architect Gridley J.F. Bryant and the Rev. Louis Dwight. Dwight made prison reform his area of expertise and served as the secretary of the Boston Prison Discipline Society. Their design followed closely their plan for the Suffolk County Jail of 1848, inspired by the 1829 Eastern Pennsylvania Penitentiary, rather than the civic institutional forms proposed by the losing architects.

The large but severe building is transitional Greek Revival-Italianate in style and cuneiform in plan, with wings radiating from an unusual, five-story central octagon. Administration and observation were placed in a central core; the wings housed the superintendent and the inmates. Much of the building’s magnificence comes from the beautifully crafted materials: the variegated gray-green and ocher ledgestone quarried by the inmates on the site and the dark gray granite trim. The unornamented exterior and ultra-plain interior (the walls in the inmates’ quarters were not plastered) objectified the building’s penal nature. In 1866, though, the State Board of Charity thought: “There is not in the commonwealth a house better adapted for the comfort of the poor.” For example, baths with hot water were provided in the basement, an amenity not realized by many wealthier folks of the period.

Although built for the city’s numerous paupers, just two years later state paupers were moved to three new state almshouses, making this one overlarge. But by 1893 it was once again crowded, necessitating the reorganization of the central core’s open spaces into new rooms. By 1913 the inmates were mainly the elderly and sick poor, and the farm operated at a loss. After the city erected a more modern almshouse with hospital facilities in 1927, the property was sold. Inmates were transferred to a new City Home for the Aged and Infirm in Fresh Pond Park in 1929, now the senior homes known as Neville Center.

In the 1920s, the Cambridge Board of Public Welfare determined that its 1850 almshouse could not be renovated sufficiently to care for its changed clientele, and the inmates could no longer work on the farm. The new population included old and sick paupers “needing a comfortable home” and general care; the “incurable chronic cases practically beyond helpful medical aid” needing expert nursing; and early stage chronic patients requiring “active hospital care for diagnosis and treatment” but rejected by hospitals due to long-term nursing needs. City officials hoped to persuade the poor elderly then getting city relief to enter the new building once it was shorn of the poorhouse stigma. A modern, 200-bed infirmary for the three groups was erected in 1928, open to all regardless of their ability to pay. Against initial public opposition, a building was erected in an 8-acre wooded section of the municipal Fresh Pond Park.

The architect, Charles Greco, tried to reduce the building’s length by bending it into a modified W shape, with a central block containing the formal entry. The red brick veneer and cast stone trim were characteristic of the neo-Georgian style then in vogue. Projecting one-story solariums at the end of each wing give the exterior extra interest and, inside, sunny spaces for the residents. Greco was popular in Cambridge. He also designed the city’s High and Latin School, two fire stations and the Main Post Office.

The up-to-date building contained 300 rooms and 450 windows, with transoms for ventilation. Although women and men were housed in 14-bed wards and smaller rooms in separate wings, under the first superintendent’s sensitive policy, several rooms were allocated for married couples. The design included a hall for church services or entertainments and a central dining room for 140 people overlooking the Fresh Pond Reservoir. The third floor held a dormitory for employees and a recreation room for nurses. Space was provided for an isolation chamber, a hospice room and a doctors’ suite and a laboratory, reflecting the medical nature of the institution.

The introduction of the federal Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965 served once again to alter the client population. The facility evolved from delivering primarily custodial care to a city nursing home in 1976. Sold to a consortium of municipal housing and health organizations based in Cambridge, it reopened as an affordable and market rate assisted-living facility in 2001 and, in 2003, a separate nursing home was added to the complex, marking a decided shift in public attitudes toward seniors in need of care.

This article originally appeared in Cambridge Day