History Hub has stories of women to celebrate changing Cambridge since Battle of Bunker Hill

Above image: Mayor Barbara Ackermann addresses the Cambridge City Council in 1972. (Photo: Digital Commonwealth)

By Beth Folsom, 2023

History Cambridge centered the stories of local women in 2020, creating as part of that effort a History Hub to highlight the many roles they have played – and continue to play – in the city’s past, present and future. In so doing, we sought to broaden the scope of our inquiry to include women from a range of periods, racial and ethnic backgrounds, classes and religions.

But why only one year? Women’s stories are still largely overlooked in the broader historical narrative, and they continue to face obstacles to their full participation in civic life, economic equality and even physical health and safety. As this Women’s History Month draws to a close, History Cambridge invites you to learn more about some of the women who have had an impact on the community and to think about stories that haven’t yet been told. Who is missing, and how can we use their experiences to create a richer, more diverse narrative mosaic?

Profiles on our Women’s History Hub include Barbara Ackermann, the first woman to serve as mayor of Cambridge. Serving first on the School Committee, then as a city councillor before and after her term as mayor, Ackermann took on issues such as the Vietnam War, public housing and health care.

Maria Baldwin, the first Black principal in Cambridge’s public schools, was known for her pioneering work in education and her activism in the realm of civil rights and racial justice. During her tenure at the Agassiz School (since renamed for her), she oversaw a dozen teachers (all white) and more than 500 students.

Anthropologist Ann Bookman graduated from Harvard University and served as policy and research director for the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor before returning to Cambridge as executive director of the Workplace Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management. Bookman has spent her long career exploring the issues of working women’s empowerment and the intersection of business, government and gender.

Sara Chapman Bull created the Cambridge Conferences – weekly “class lectures” held at her home whose purpose was “to afford opportunity for the comparative study of ethics, philosophy, sociology and religion.” A significant number of important philosophers and religious leaders of the day lectured at the conferences. Bull was also a prominent supporter of Swami Vivekananda, founder of the Vedanta philosophy, and of cross-cultural work in education and science in India and the United States.

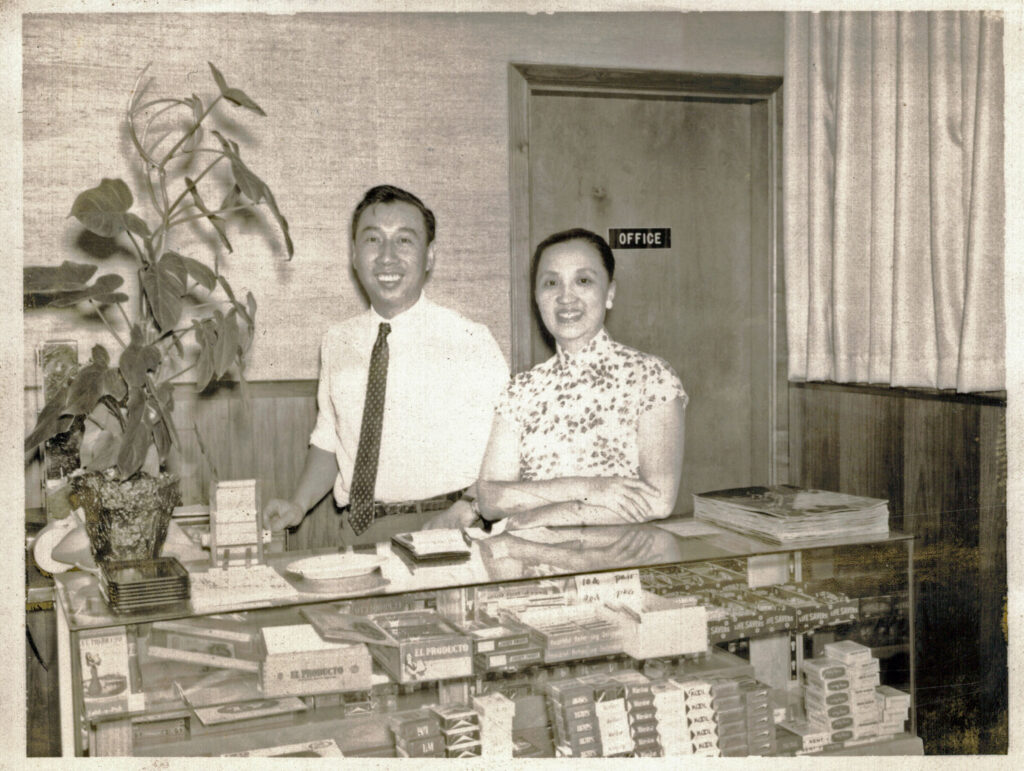

In her work as a chef, restaurateur and entrepreneur, Joyce Chen introduced generations in Cambridge and beyond to Chinese cuisine. She opened her first restaurant in Cambridge in 1958 and, over the next four decades, helped to popularize such dishes as Peking ravioli, moo shi pork and scallion pancakes. Chen parlayed her skills in the restaurant industry into a successful line of food products and cookware, ensuring that her legacy would travel well beyond the Cambridge area.

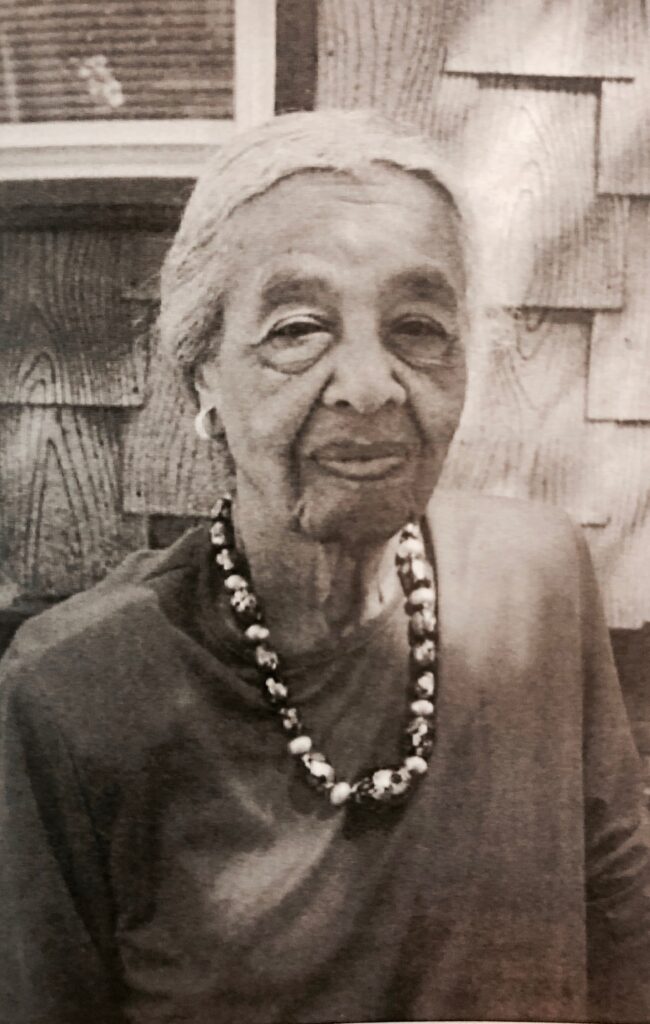

Helen Lee Franklin, a teacher-turned-social justice advocate, journeyed from the South to the Boston area in the early 1900s and had strong ties to the small but active Black community in Cambridge. After graduation, Franklin returned to the South to teach in a number of schools providing education to Black students. Returning in the late 1920s, she was active in the founding of the Cambridge Community Center, as well as supporting the Boston Urban League and other local organizations working for racial justice.

A fifth-generation Cantabrigian, Suzanne Revaleon Green was a schoolteacher for many years at the Houghton and Roberts schools. In addition to her professional work with the city’s young people, Green volunteered for the Girl Scouts, the Cambridge Community Center, the YWCA and the Cambridge Historical Commission. Green was also a co-founding member of the Cambridge African American Heritage Trail and, as a result of her decades of dedicated service to Cambridge, was given a key to the city on her 90th birthday.

Lois Lilley Howe was one of the first women to graduate from MIT’s architectural program, the organizer of the only all-woman architectural firm in Boston in the early 20th century and the first woman elected as a fellow of the American Institute of Architects. With partners Eleanor Manning and Mary Almy, the firm of Howe, Manning & Almy completed more than 500 projects over 43 years of practice. Many of these buildings are still standing, including in Cambridge.

A pioneer in early childhood education, Edith Lesley founded the Lesley Normal School in 1908; in 1944 it became Lesley College and began to offer four-year undergraduate degrees in education to women. Over more than a century, Lesley expanded its courses of study to the social sciences and related fields, educating generations of teachers, social workers and mental health counselors, many of whom work or consult in Cambridge schools.

Eva Neer trained as a biochemist in the 1950s and 1960s, thinking she would have a career as a research scientist studying biological proteins and their signals. In 1980, as a researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Neer discovered a class of one of the most abundant signaling proteins in the brain. As a result of her decades of work and discovery, in 1990 she was promoted to full professor at Harvard Medical School, only the second woman to attain this rank in the history of the school’s department of medicine.

Although she is often referred to as “Dr. Joseph Warren’s fiancee,” Mercy Scollay was a political thinker in her own right, and her connections to others in the Revolutionary generation continued long after Warren was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill. In the wake of Warren’s death and her subsequent loss of his children, to whom she had become a surrogate mother, Scollay grieved but was able to strengthen her existing familial support networks and embark on new endeavors – including her decadeslong correspondence with other Revolutionaries and her quest to secure financial support from the state for Warren’s children.

Elizabeth Ann Sullivan was one of the first – if not the first – women to attend Tufts Medical School, graduating in 1914 and becoming chief resident physician at the Women’s Reformatory in Framingham. After a successful career there and in New York, Sullivan moved to Cambridge and, among her many professional and volunteer pursuits, worked with women arriving from war-torn Europe, providing them with free medical care and helping them navigate their new lives. Sullivan also organized and helped lead our Civil Defense Agency and was the director of the local chapter of the Red Cross.

In 1975, Phyllis Wallace became the first Black woman – and first woman – to get tenure at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Early in her career, Wallace studied and taught international trade but, in the 1950s she turned her attention to the Soviet economy as the United States was at the height of the Cold War. In the 1960s, Wallace began to focus on racial disparities in the American economy, and combined her studies of race, gender, and politics and their effects on workers and economic systems.

The 13 women profiled in the History Hub span several centuries and represent a variety of racial and ethnic groups and professions. But this is by no means an exhaustive list of change makers. Our Hub is always growing, and History Cambridge would love to hear from you: Whose stories should be added to our collection? We welcome suggestions for new profiles, as well as submissions by the greater community. Together we can create an even richer picture of the many women who have worked to make Cambridge a better city.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.