Celebrations of Washington’s Birthday reflect tangled legacies of immigration, integration

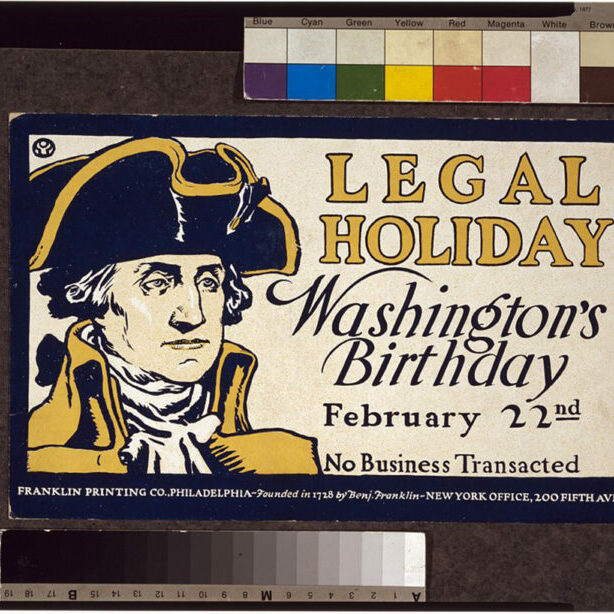

Above image: An early 20th century sign for Washington’s Birthday. (Image: Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons)

By Beth Folsom

George Washington’s birthday became a day of remembrance almost immediately after the death of the first president. Just two months after Washington passed away in December 1799, Americans marked what would have been his 68th birthday on Feb. 22, 1800, with solemn reverence. The nation was still in mourning for its former leader, and the earliest commemorations centered on collective grief for the late president and an almost religious reverence for his impeccable character in civil and military life.

Throughout most of the 19th century, Feb. 22 was celebrated around the country by parties, parades, concerts and public orations, but these commemorations were organized independently by cities and towns, or by county- or state-level governments. It was not until 1879 that President Rutherford B. Hayes signed the order to make Washington’s Birthday a federal holiday. In its first incarnation, the bill applied only to the District of Columbia, but in 1885 its scope was expanded to include the entire country. At that time, Washington’s Birthday was only the fifth nationally recognized bank holiday – the others being Christmas, Thanksgiving, New Year’s Day and the Fourth of July – and the first to celebrate an individual person (it would take another century for the creation of a second holiday honoring an individual, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was formalized in 1983).

Passed in 1968 and taking effect in 1971, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act shifted certain holidays from a specific calendar date to a series of predetermined Mondays. This change applied to Columbus Day, Memorial Day and Veterans Day (which was later returned to its fixed Nov. 11 commemoration), as well as Washington’s Birthday, which was moved from Feb. 22 to the third Monday in February. Congress used this opportunity to combine Washington’s birthday with that of Abraham Lincoln (Feb. 12) to create Presidents Day, which soon grew beyond Washington and Lincoln to celebrate all U.S. presidents.

In 19th-century Cambridge, however, the veneration of Washington on this date was well-known and frequently practiced. Local newspapers abound with notices about concerts, lectures and public orations in celebration of Washington’s legacy, given by religious, governmental and civic organizations. The holiday was also an opportunity for Cantabrigians of all ages to hold parties, dances and other entertainments, as well as for sporting events and contests. And in the city’s schools, patriotism was on full display as students dressed in colonial garb and waved flags while reciting poetry and performing songs that aimed to capture the self-sacrificing spirit of the first president.

Much of the celebration of Washington’s birthday centered around his love of country, his willingness to put the needs of his soldiers and his country before his own, and his example of the peaceful transfer of power from one elected official to another. But despite Washington’s portrayal as a leader for all Americans, an examination of the various ways in which his birthday was commemorated shows that many of those who celebrated were crafting a legacy for Washington that was not as inclusive as it may seem. This was particularly true in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the formal end of legal enslavement was giving way to the difficult realities of creating a racially integrated country and as the number and countries of origin of international immigrants was changing the population of Cambridge and the nation as a whole.

Even in a Northern city such as Cambridge, the perceived threat of these demographic changes led to apprehension and even anger on the part of some residents. The ways in which they chose to commemorate Washington’s birthday reflects these fears and prejudices in ways that are blatantly racist and more subtly xenophobic. Beginning in the late 19th century and continuing through the World War II era, many local organizations began using Washington’s birthday as an opportunity to instill in the immigrant community the desire to become patriotic Americans.

In the 1910s and 1920s, as the country was embroiled in and recovering from World War I, the American Legion and other civic groups encouraged Naturalization and Citizenship Weeks for foreign-born residents during the week leading up to Feb. 22, culminating in citizenship ceremonies on Washington’s birthday. These efforts were accompanied by lectures and public discussions that, while seeming to welcome those from abroad to settle into American life, did so at the expense of the cultures and traditions of their home countries and often denigrated other parts of the world. Foreigners could become Americans, these programs said, as long as they shed the language and customs of their homes and assimilated into mainstream U.S. society.

Another means of celebrating Washington’s birthday came in the form of minstrel shows – comical performances featuring Caucasian actors in blackface, speaking and singing in an exaggerated dialect meant to mock the language and mannerisms of enslaved Black men and women. The particular minstrel shows performed for Washington’s Birthday dealt specifically with the story of Washington’s life, and the minstrel performers provided the comic and musical interludes and also served to portray the enslaved individuals who worked for Washington at his Mount Vernon estate and traveled to serve him on his military campaigns.

Many of these minstrel shows took place in jails and prisons, where the prisoners would play the parts (Black and white) while outside audiences – often including elected officials and other local elites – enjoyed the performance. A 1903 Cambridge Chronicle article reports that inmates at the East Cambridge jail put on a show in which a correctional officer played the role of Washington and prisoners played the parts of “Tambo” and “Bones” – two stock characters in minstrel shows who embodied different (and racist) Black stereotypes. The plot of the show included episodes from Washington’s public and private life in which he was served by enslaved Black people. By recounting Washington’s heroic deeds in the context of his lifelong status as an enslaver, these minstrel shows further linked Washington’s legacy to his ownership of human property, and ensured there was room for both the ideals of liberty and the reality of racial hierarchy in Washington’s America. The fact that these performances were held in prisons, with prisoners playing the parts of the enslaved, adds yet another layer to this complex form of commemoration.

While Washington’s birthday has merged with Lincoln’s birthday to become Presidents Day, celebrating all U.S. presidents, the complicated history around its commemoration in Cambridge and beyond illustrates the ways in which Washington has been held up as an icon of patriotic loyalty and also used as a symbol of ethnic and racial superiority. Different aspects of Washington’s life and story came to the forefront of these celebrations at different times in the city’s history, with individuals and groups choosing the parts of Washington’s story – real or invented – that supported their vision of who and what America should be.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.