You can pick up delicious fresh produce Thursday at what was the North Cambridge ‘Poverty Plain’

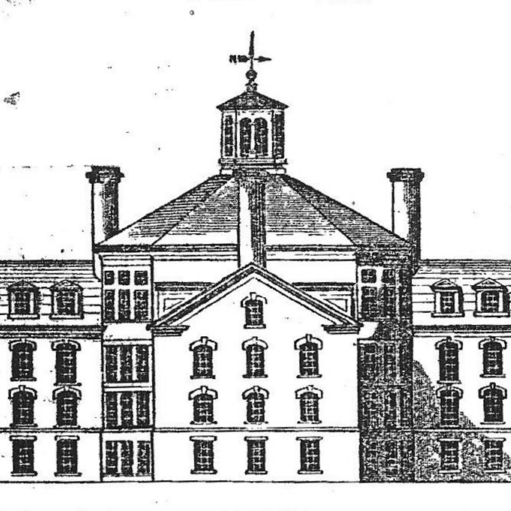

Above image: Sketch of the Almshouse at the North Cambridge Poor Farm, 1852. (Image: Cambridge Chronicle)

Did you know that much of Cambridge was once farmland? In a joint event by History Cambridge and Farmers to You on Thursday, you can enjoy local produce while learning about local history, particularly the Cambridge Poor Farm and its role in the history of North Cambridge.

Long before the arrival of European colonists, the Indigenous people who called this land home cultivated the landscape to grow crops. When the colonists arrived, they melded their traditional farming methods with Indigenous practices to establish farms, orchards and other means of sustaining their settlements. As Cambridge became increasingly populous and industrialized over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, these larger plots of farmland shrunk to individual gardens and small groves of fruit trees, but the city maintained a larger-scale farm in North Cambridge as part of its efforts to care for and control the part of its population who were considered unable to support themselves. This would come to be known as the Poor Farm – the agricultural land next to the city’s almshouse that served the dual purpose of providing food for the almshouse residents and teaching them the redeeming benefits of agricultural labor.

British colonists brought their ideas about caring for those needing material support with them from their homeland, and their approach to providing for orphans, paupers, the elderly and those deemed “insane” reflect the model used in England. Until the mid-19th century, each town was responsible for its own dependents, and no community willingly gave aid to outsiders. Cambridge’s needy were boarded out to families at the expense of the town until 1779, when the selectmen bought a building near Harvard Square to serve as a “poorhouse.” Its residents were referred to as “inmates,” and all who were physically able were required to work to support their upkeep, either by raising produce or by working in a craft or trade, often alongside the families with whom they were boarding.

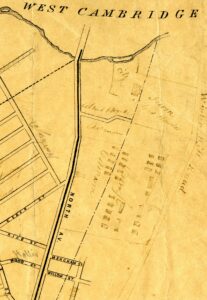

In 1849, Cambridge (which had recently become a city) acquired a 32-acre farm in the North Cambridge neighborhood and, in 1851, residents of the city’s poorhouse were relocated to what was then known as “Poverty Plain.” At this time, North Cambridge was still very much a developing area of the city, sparsely populated and relatively remote, which the city government saw as an ideal place to put a population they wanted to hide from public view. To make the new almshouse self-supporting, its residents quarried stone for the building from a nearby ledge. When the settlement was completed, they used the farmland to cultivate a variety of crops, as well as raising livestock and catching fish in Alewife Brook using the Indigenous fishing methods – including the creation of fishing weirs – that colonists had learned from the Native peoples who had been using them for thousands of years.

The almshouse on the Poor Farm property was built by the Rev. Louis Dwight and architect Gridley J.F. Bryant. Influenced by the American prison reform movement of the 19th century, Dwight and Bryant sought to make the building and its surrounding grounds a place where those who were able could be “redeemed” and lifted out of poverty through vigorous physical labor, especially farming. Although there were recognized differences between the “deserving poor” – orphans, widows, the elderly and infirm – and those whom society portrayed as creating their own misfortune (through laziness, drunkenness and petty crime), all of those who depended on state support were housed together in the almshouse through the early 20th century. By the 1920s, state orphanages, mental hospitals and cash grants to the poor had replaced the almshouse system and, in 1927, Cambridge sold its Poor Farm property, with a portion going to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston and the rest to private developers.

The social reformers who championed the Poor Farm and its perceived ability to instill the values of hard work and self-sufficiency to indigent Cambridge residents were employing the latest in rehabilitation practice for their time. But the insistence that the poor needed to “earn their keep” by laboring in difficult conditions (the area’s soil was clay-laden, making crop cultivation especially hard) illustrates the 19th-century conception of poverty as a moral failing of the weak that needed to be remedied through instruction by those in the upper classes and the discipline imposed by manual labor. Changing attitudes toward the poor in the 20th century have resulted in a better understanding of the factors that lead individuals to need public support, as well as what that support network entails.

On Thursday from 2 to 3:30 p.m., Farmers to You and History Cambridge will share food (including locally grown apples, a fall favorite) and history at their North Cambridge pickup site at 147 Sherman St. Started as a means by which to connect people to the farmers who grow their food, Farmers to You now helps more than 1,900 families in Vermont and Greater Boston get food from small-scale farmers and producers each week, year-round. Farmers to You’s mission is to sell local and consciously sourced food, pay farmers a fair price for their produce and build a system that minimizes waste while promoting sustainable growth and regenerative farming.

Most Farmers to You customers get their farm shares each week at pickup sites, including the Sherman Street site in North Cambridge. These sites are not only places where customers pick up food from local farms, but also where the community can share recipes and stories. History Cambridge is excited to join this community, to learn more about North Cambridge and to share our History Kit, which includes opportunities for hands-on exploration of the natural and human history of the neighborhood and the city.

To learn more about the organization, including its mission and opportunities to get involved, visit farmerstoyou.com. Sign up for our newsletter to find out more about our events and local partnerships, and we look forward to seeing you Nov. 2 in North Cambridge.

Beth Folsom is programs manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.