A Lost Park: Longfellow’s Parklands

By Annette LaMond | S.M., MIT Sloan School of Management | Ph.D., Yale University

There are various lenses through which to view the history of a city, and the treatment of open space and development of parks may be as revealing as any other. This is particularly true in Cambridge – one of the most densely populated small cities in the country – where the value of land is high and the preservation of open space, even existing parks, can be controversial.

One Cambridge park is of particular interest not only because of the story of its creation and its forgotten history, but also on account of its potential future. That park is a 2½-acre triangle of Department of Conservation and Recreation parkland, bordered by the Charles River, Hawthorn Street, and Mt. Auburn Street, and truncated – 50 years after its creation – by an extension of the four-lane Memorial Drive.

The piece provides a history of the park – first in overview, then in more detail, followed by a section of photographs.

Overview

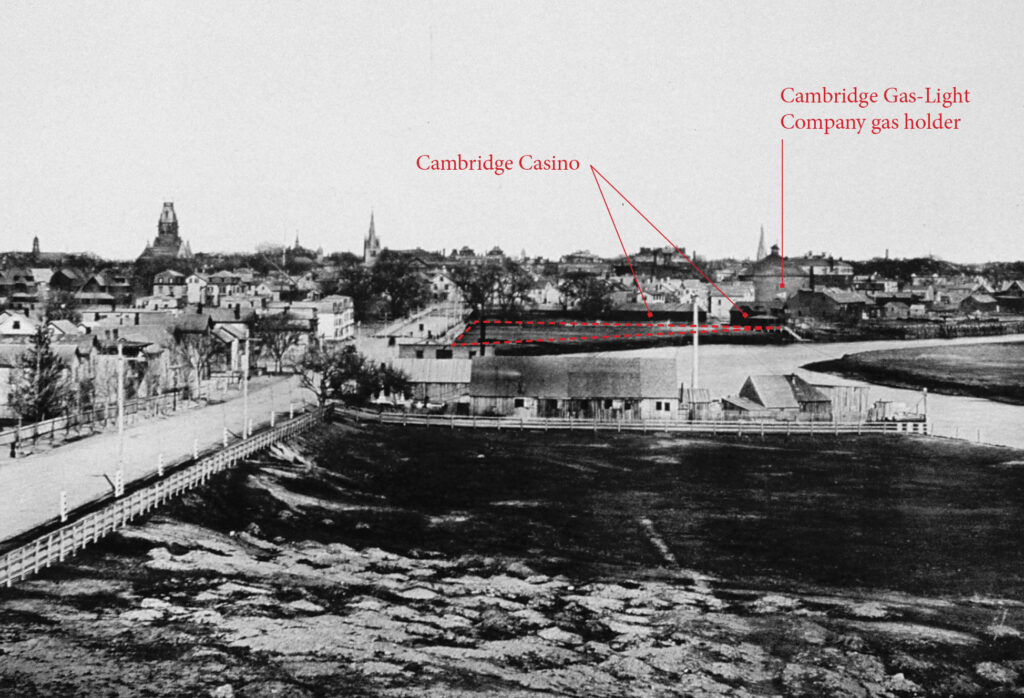

This riverfront land, now part of Riverbend Park, was not foreordained to be a park. When Cambridge was settled, it was marshland, subject to flooding and a breeding ground for mosquitoes. With immigration and industrialization, the river became the city’s commercial front, and its marshes were degraded by tidal washes of noisome effluent and mud. The stretch that is the subject of this paper was no exception. Photographs from the second half of the 19th century show wharves and warehouses on either side of the future park. Abutting on the east was the Cambridge Gas-Light Company’s gas holder – an imposing circular brick structure. On the west, a commercial wharf spanned the mudflat.

However, this small riverbend parcel remained open, thanks to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1809–1882), who acquired it in 1870 (along with the hay-meadows across the Charles River) to conserve its views and open space. Longfellow’s visionary purchase came some 20 years before the City of Cambridge committed to establishing municipal parks. Had the poet not acquired this stretch of riverfront, and had his children not later given it to the Longfellow Memorial Association, the portion along Mt. Auburn Street would likely have been filled in with apartment buildings and storefronts, leaving only a narrow strip of open land at river’s edge.

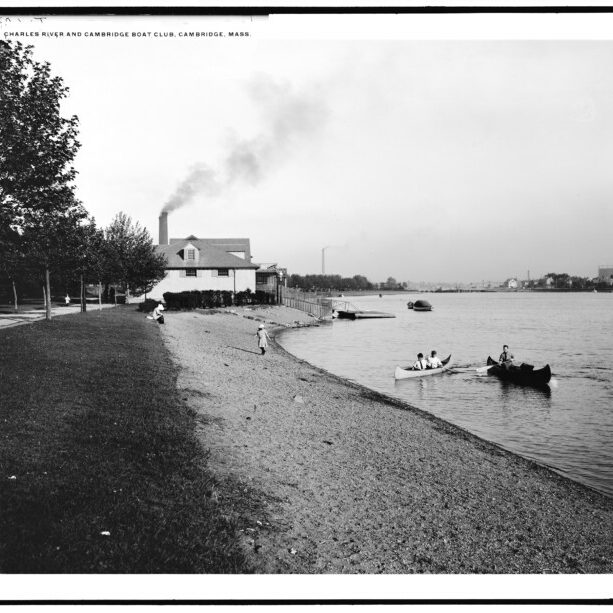

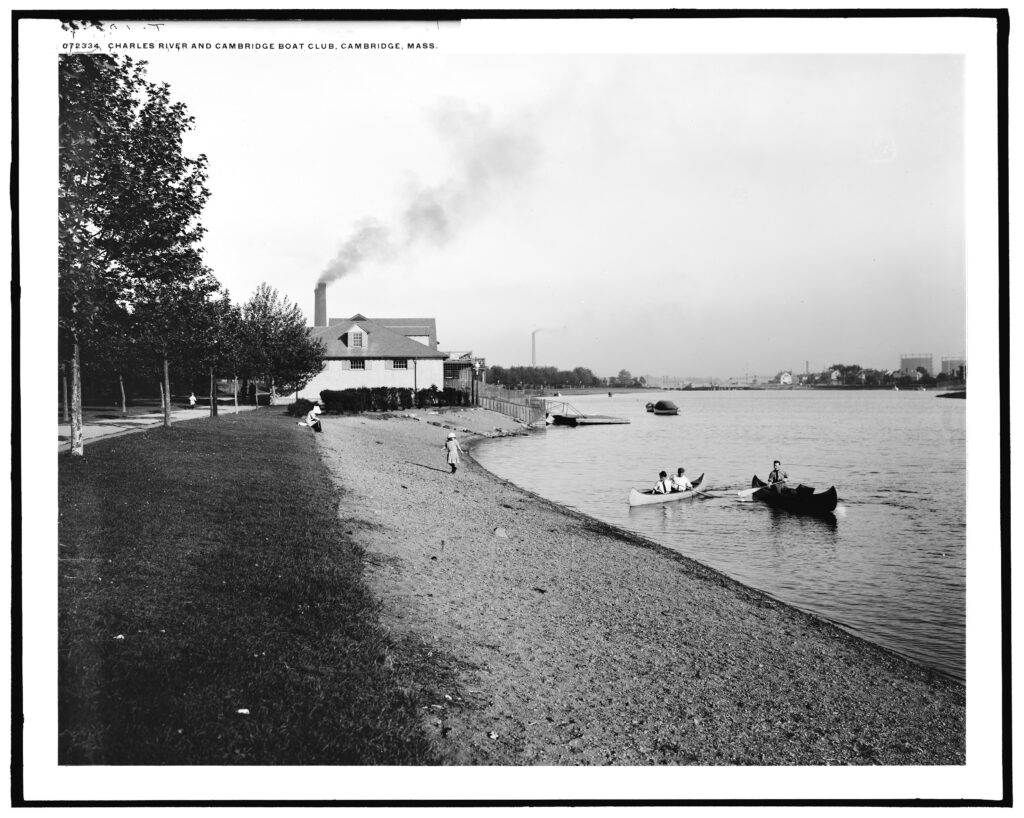

Thus, by good fortune, Longfellow’s marshes were open when Cambridge embarked on its 1890s riverbank improvement project – a project that transformed the city’s riverfront. A decade later, the appeal of the new parkland along the river was further enhanced by the construction of the Charles River Dam. As for Longfellow’s park, its prime location offered access to swimmers and rowers, and in cold winters, to ice skaters. For others, the park provided a peaceful refuge in all seasons.

Longfellow’s one-time marshes became the nucleus of a prototypical people’s park – one whose history has gone largely unrecorded. The park’s story was shaped by a remarkable outpouring of civic activism that began in 1912, when a private neighborhood association was formed to raise funds for park improvements to benefit the children who lived in the small workers’ cottages of the nearby Marsh District. The association’s first project was to add playgrounds. Then, at the group’s urging, the city provided a bathhouse with an attendant.

Enhancing the interest of the park, the association sponsored children’s gardens at the corner of Willard and Mt. Auburn streets, on a one-plus acre field lent for the purpose by Longfellow’s youngest daughter, who had inherited it from her father. On an adjoining parcel, between Ash and Hawthorn streets, the Cambridge Boat Club, founded in 1909, further enlivened the area. On the west side of the park, a narrower strip along the river led to more open parkland at Gerry’s Landing, where a beach was added around 1916. Taken together, this riverfront must have felt, at least to children, like a paradise playland.

From the beginning, the Longfellow parkland faced the threat that a road would be run through it. When the Cambridge River Road was built in 1897, it terminated at Hawthorn Street, leaving the question of a connection to points west unresolved. One option was a parkway at water’s edge to Gerry’s Landing. Of course, in the 1890s, those parkway advocates foresaw only “Roads for Light Traffic.”

In 1930, the state proposed that Memorial Drive be extended. (The parkway had been renamed Memorial Drive after World War I.) The park’s neighbors – from the Marsh District to Brattle Street – united in protest. The protests were successful and the road proposal did not advance, though work done in anticipation of authorization did some damage to the park’s banks and the beach at Gerry’s Landing. However, that damage was repaired, the Depression set in, and life went on.

After World War II, the state’s road planners re-mobilized, this time with determination that they would prevail. The proponents of the road ignored the pleas to save the park, focusing instead on the private Cambridge Boat Club, which was said to be standing in the way of progress. Despite the neighborhood’s protests, the planners succeeded, citing the urgency of a new road for commuters. By 1950, Memorial Drive had been extended along the river – through the Longfellow and Gerry’s Landing parkland, and the Cambridge Boat Club moved to Gerry’s Landing, further reducing that parcel and its bathing beach. A stretch of riverfront that had offered open space and recreation for five decades was given over to motorists.

Memories of the once vibrant park were forgotten until the 1970s, when Isabella Halsted who had known the park as a child led a campaign to close the parkway on Sundays from spring to fall. She succeeded, and since 1975, the closing of Memorial Drive has brought renewed life to the park, if only one day a week. People have flocked to the riverfront on Sundays, and this year, on Saturdays as well.

Inspired by the popularity of the Sunday road-closing, the DCR offered the possibility of a partial lane reduction in a master plan for the Charles River Basin that was completed in 2002. But that recommendation has not been implemented.

Now the DCR is engaged in a Memorial Drive Greenway Improvement project – from the BU Bridge to the Eliot Bridge at Gerry’s Landing. At the project’s initial public meetings in the spring of 2019, the concept of a “road diet” was favorably received. Indeed, some people called for removing the road altogether. Although Covid-19 led to a suspension of planning, the pandemic served to underscore the importance of outdoor space in a densely populated, “under-parked” city like Cambridge. Appreciation for open space and time spent outdoors has grown, and Riverbend Park looks more valuable than ever. With the resumption of DCR project planning, the history of Longfellow’s parkland should be considered anew.

Is there a chance of restoring the parkland and its recreational potential? To understand Riverbend Park’s history may be to reimagine its future – to a restoration of the beauty that Charles Eliot praised and the recreational enjoyment that the early civic activists envisioned.

The History of a Landscape

Longfellow’s Acquisitions Preserve a Landscape

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow first came to the Craigie House in 1837, more than 60 years after the Brattle Street mansion had served as Washington’s headquarters during the Siege of Boston. Longfellow was then a 30-year-old widower, restarting his life as a professor of modern languages at Harvard. Looking for a lodging in Cambridge, he happened to visit a friend, who rented rooms in the historic house. The poet later recalled that it was a beautiful summer afternoon, and though “the window blinds were closed…through them came a pleasant breeze and I could see the waters of the Charles River gleaming in the meadows.” When his friend moved, Longfellow was able to persuade Mrs. Craigie to rent him two rooms. Longfellow’s journals over the next years record his continuing delight in the house and its surroundings.

In 1843, Longfellow remarried, and brought his new wife Frances (Fanny) Appleton, the daughter of a wealthy Bostonian, to the house, then owned by Mrs. Craigie’s heirs. The couple began their tenure in the house as renters, occupying half of its rooms. Like her husband, Fanny was drawn to the house’s historical associations, and persuaded her father to purchase the house and some five acres of surrounding land. A generous wedding gift!

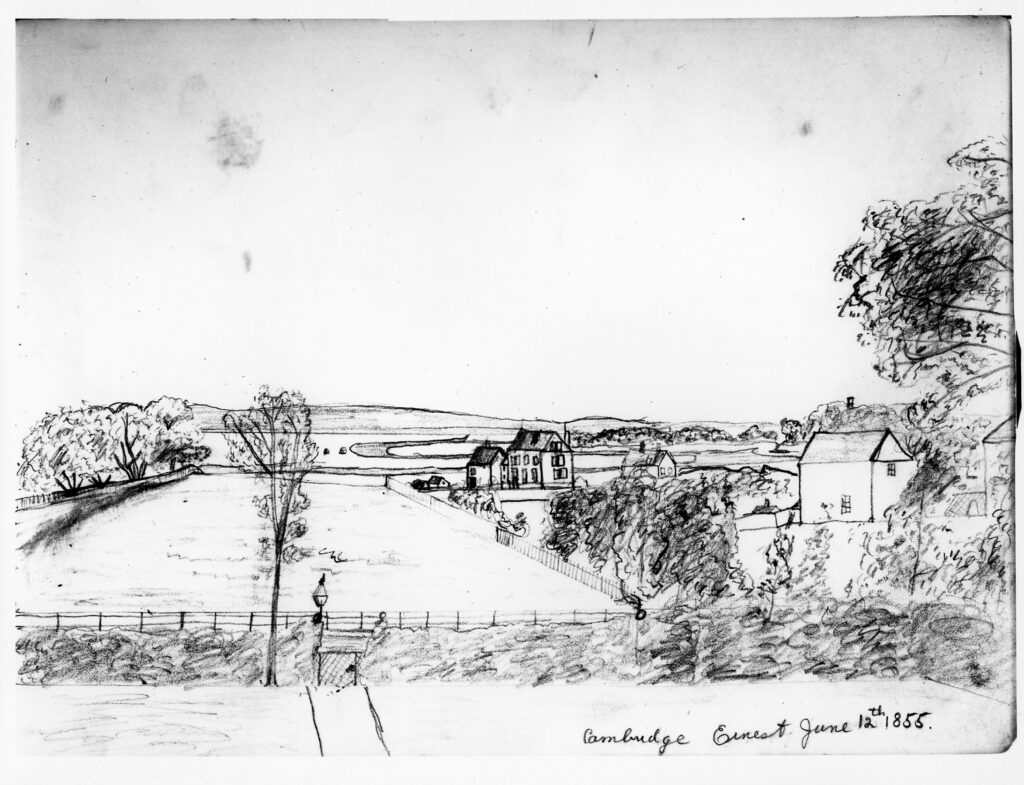

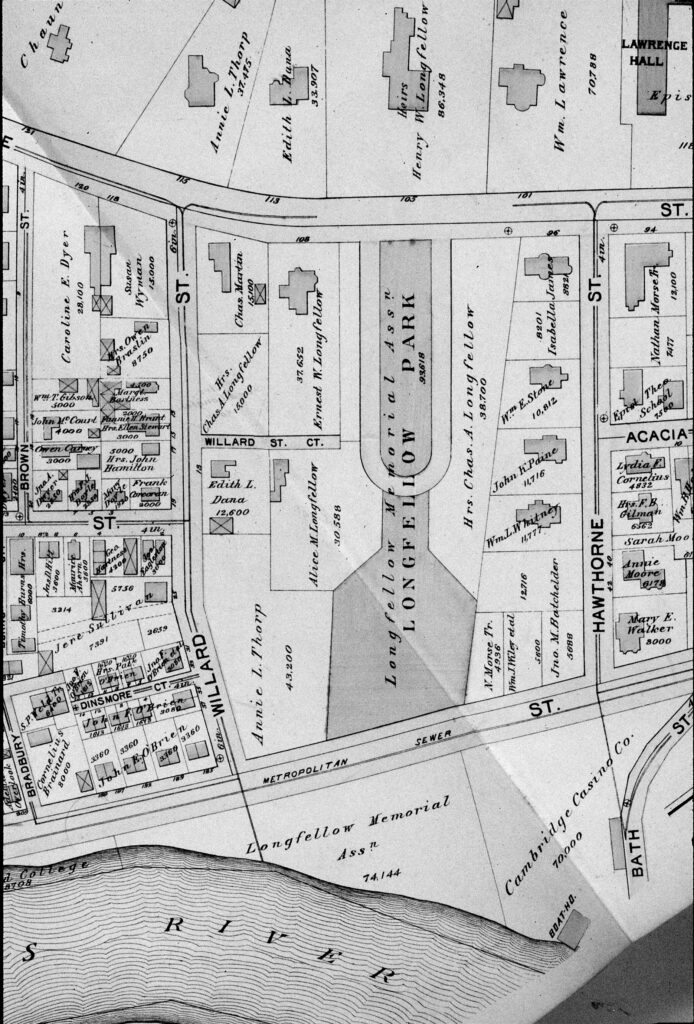

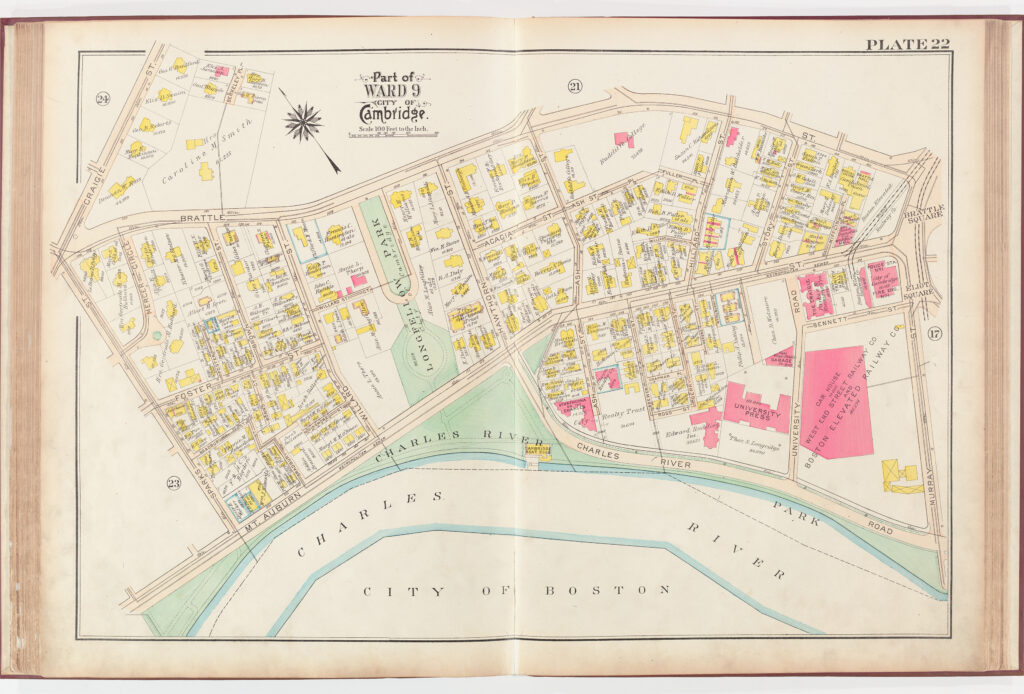

Concerned with preserving the house’s view to the Charles River, Fanny also prevailed upon her father to purchase an additional four-acre parcel directly across the street. Mr. Appleton did so, later selling the land to his son-in-law. With a continuing interest in the preservation of the view from the house, Longfellow continued to buy adjacent land. By the early 1870s, he had added 2¼ acres to the meadow between Brattle and Mt. Auburn streets, as well as a triangular lot (nearly two acres) between Mt. Auburn and the Charles and the Brighton meadows (some 70 acres) across the river.2 [Images 1–3]

Longfellow’s Landscape Becomes Parkland

Longfellow died in March 1882. Within weeks of his death, a memorial association was formed with the goal of raising money to create a park with a lasting memorial. The next year, Longfellow’s children donated two acres between Brattle and Mt. Auburn streets for a formal park; five years later, the heirs gave the association the parcel that extended from Mt. Auburn Street to the river. The riverfront land was transferred twice more, from the association to the city in 1894, when the city had committed to a riverbank improvement project, and then to the metropolitan park system in 1921. Although land was a key to preserving the visual connection from the Longfellow’s historic mansion to the river and the meadows and hills beyond, it was not given a place name to reflect the Longfellow connection.

What was the condition of this riverfront parcel? A circa 1887 photo – a view of Mount Auburn Street, looking east – provides an overview of the Longfellow parcel and its surroundings. [Image 4] Not a promising sight, but change was only a few years away. Soon after the photo was taken, the city formed a park commission to develop recommendations for a park system. The commission worked with dispatch, completing a report by late 1893. A priority recommendation: reclamation of the city’s riverbanks – an enormous project, but one offering benefits to the entire city.

Regarding the Longfellow parcel (which extended back from the river), the report recommended that the low marshlands along Mt. Auburn Street be acquired by the city and made a portion of the Longfellow park between Mt. Auburn and Brattle. Following the report, the city moved quickly to acquire the riverfront in order to begin the work of transforming foul-smelling marshes and mudflats into parkland. The Longfellow Memorial Association conveyed its riverfront parcel to the city in 1894.

As for a river road, the city’s plans describe a “drive” along the embankment from Harvard Bridge to connect with Fresh Pond Parkway. However, those plans did not include a road through the Longfellow park. (The bank to the west of the Longfellow land was too narrow to accommodate a road.) Accordingly, two road options were suggested: one from Boylston Street (now John F. Kennedy Street) along the shore up to Hawthorn and Mt. Auburn, widened to a “handsome boulevard,” and the other a drive via Eliot Street to Brattle Street. The assumption was for light traffic.

The first section of the river drive in Cambridge – the Charles River Road – was the stretch from Boylston Street (JFK Street) to Bath Street (now Hawthorn Street). The preparatory land-taking was less complicated here. Despite some difficulty (quick sand and deep peat deposits), the marsh was filled with carloads of ashes and gravel, and the riverfront graded and sloped. The shoreline was given a naturalistic treatment, and the road lined with London plane trees, the first of which was planted on Arbor Day – April 22, 1897. The work was viewed as an “object lesson” to demonstrate how the noxious mudflats and marshes could be transformed into parkland. [Image 5]

As for the park at the end of the Hawthorn Street terminus of the river road, Charles Eliot, the landscape architect responsible for the city’s riverfront plans, saw opportunity in the open space that was the Longfellow parcel. Not only did it connect the poet’s memorial park between Mt. Auburn and Brattle streets with the river, it provided a contrast from the narrower band of riverfront parkland to the east. In Eliot’s opinion, the prospects from the park made it the most “peacefully beautiful landscape that Cambridge is ever likely to possess.”

The filling of the area across from Willard Street was quite a production – the fill depressed thousands of cubic yards of mud into the river, which in turn required dredging. To retain the fill, it was necessary to build a 300-foot bulkhead.

Before and after photos of the riverbank to the west of Hawthorn Street taken in 1899 and 1900 reveal the shoreline transformation of the Longfellow parkland. [Image 6 A & B] What was the view to the east? A “before” photograph, east-looking, would have shown the Cambridge Gas-Light Company’s gas holder at the foot of Ash Street. A feature of the landscape since 1852, the circular brick structure enclosed an inverted iron tank that rose and fell in a water seal. The gas holder (visible in Image 4) was razed in 1900, so an “after” photo would have shown an open tract of land. That tract was filled between 1914 and 1924, by five apartment buildings, the Strathcona, Barrington Court, Hampstead Hall, Radnor Hall, and the Allwyn. Along the riverfront the Cambridge Boat Club clubhouse was added to the view in 1909.

Photographs of the park in its early years remain to be discovered, but the 1916 Bromley map shows the design of the park – granite-edged paths, one lining up with the central axis of the Longfellow Park, and a circle at the corner of Hawthorn and Mt. Auburn. [Image 7]

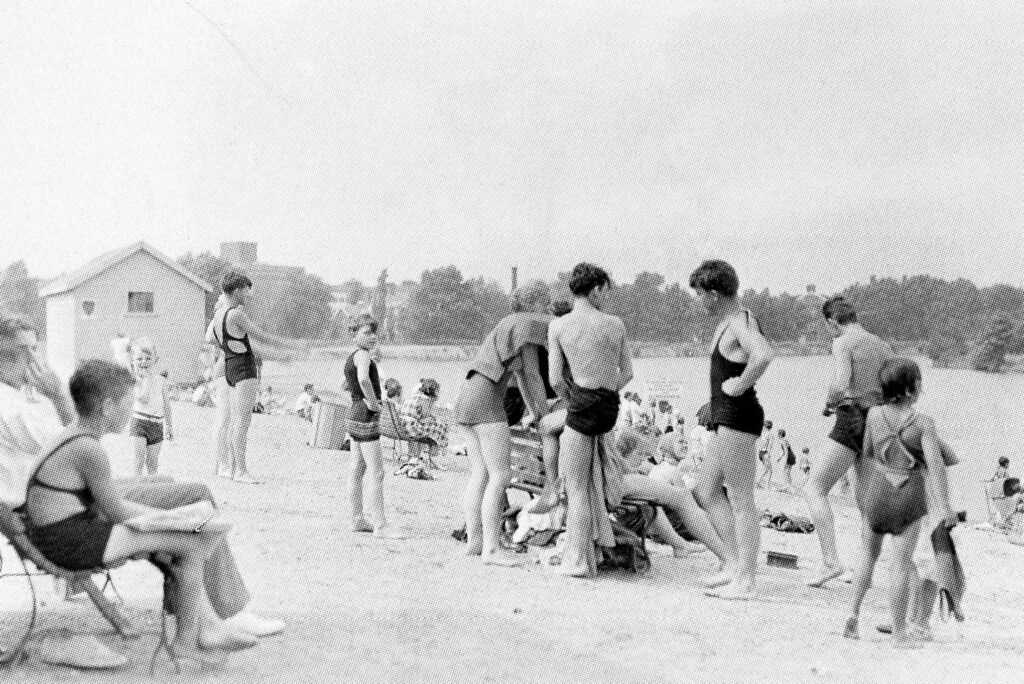

Though photographs are wanting, a series of articles in the Cambridge historical newspapers provide considerable coverage of activities in the park. Of course, it is not surprising that the park was well used, given the its proximity to a densely populated neighborhood – the Marsh District, built up in the 1850s primarily by Irish immigrants. The district worker’s cottages – small and closely spaced – were home to hundreds of children. The Longfellow riverside park was their backyard. [Image 8]

Enclosing the Marsh District on its other sides were Brattle, Mercer Circle, Hubbard Park, and Lowell streets with their commodious homes and more spacious lots. Remarkably, around 1912, those neighbors formed an organization to develop a children’s community in the park. Sponsored by Longfellow’s three daughters and Harvard’s president emeritus, among others, the organization adopted the name Longfellow Improvement Association, and raised funds from a roster of prominent citizens. One supporter – William Fenwick Harris, a classics scholar and knowledgeable gardener – gave particularly generously of his time. It is thanks to Harris’s talent for publicity that the Cambridge newspapers covered the association’s work in considerable detail.

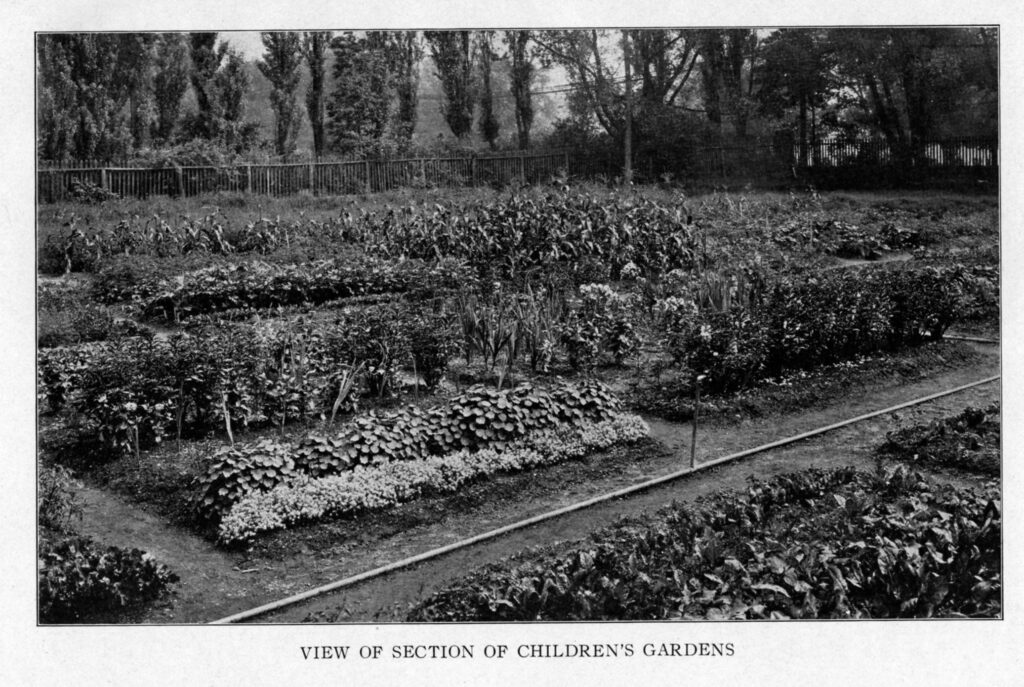

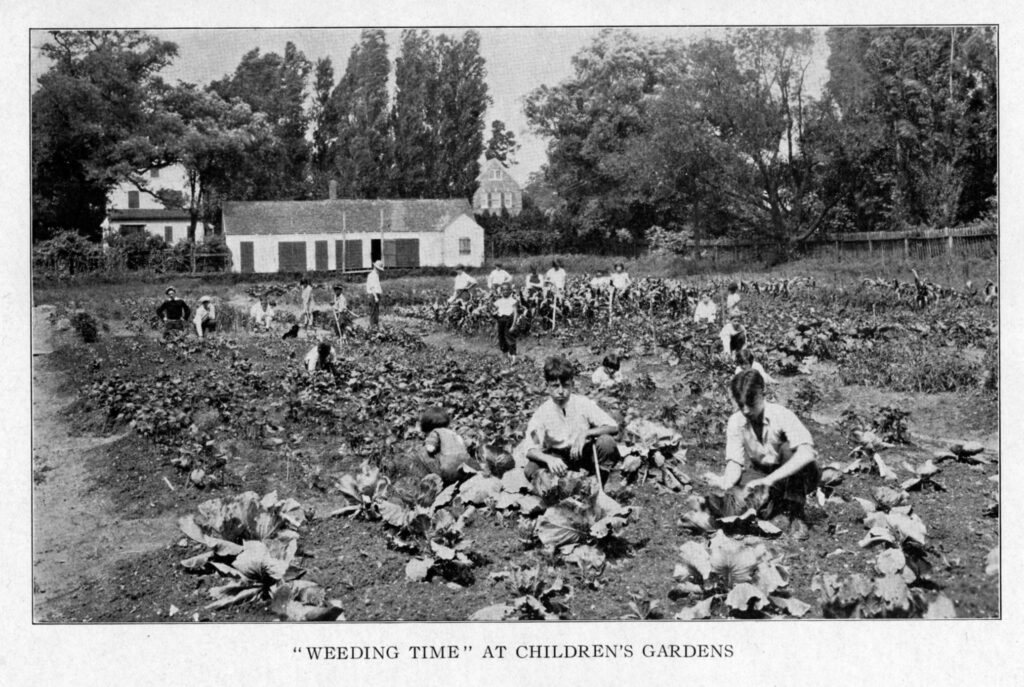

A news article published in July 1915 describes the association’s work in creating “the best developed children’s community in Cambridge.” The effort included children’s gardens, a new playground, and a children’s bathing beach, reaching “practically every boy and girl of the community.” More than 100 children had garden plots on the field, lent by Annie Longfellow Thorp, at the corner of Willard and Mt. Auburn streets. (A one-time bowling alley that had been moved to the site 20 years before provided shelter and bathrooms.) [Images 9 and 10 A & B]

Supervised by a trained teacher, a woman farmer, and several assistants, the children also participated in a community government. The association established playgrounds in the park – used by several hundred children each day – with trained instructors. Within a few years, the city took over the playground work, and also built a bathing beach and bathhouse with a caretaker near the playground and gardens. The city even installed a water fountain. (After 1915, the bathing facility was moved to the parkland at Gerry’s Landing, a short walk from the Longfellow triangle.) [Images 11 and 12] There were parents’ days, excursions, field days with picnics, games, swimming races, boat trips and prizes plus fireworks and speeches by the mayor. The children’s garden activities continued until World War II, when the field became a general community garden.

What of the road-builders’ plans? In summer of 1930, the Metropolitan District Commission announced plans to extend Memorial Drive along the bank of the Charles River, severing the park’s waterfront. People protested that the proposed road would ruin the park – a park that was heavily used by area residents who were “actually” in the city during the summer. The Cambridge League of Women Voters led the campaign against the road, circulating a petition with a counter road proposal that was signed by 585 citizens, the first signature being that of Congressman Frederick W. Dallinger, who lived on Linnaean Street – not far from the park.

Opponents of the road appealed to history, arguing that the commission’s plans for the new boulevard were contrary to the wishes of the donors of the parkland. They, including Longfellow’s only surviving child, Mrs. Thorp, noted that Longfellow’s heirs had given the land to the Longfellow Memorial Association with the intention that it would be a “breathing space on the river” – that it “will one day be a great boon to Cambridge when it becomes crowded and would be a better monument to [their] father and more in harmony with his character than any graven image that could be erected.”

The initial coverage of the case against the road extension in the Cambridge papers was sympathetic. Then the proponents of the road struck back. They did not speak to the park, instead attacking the Cambridge Boat Club, located in the path of the proposed road, as standing in the way of “progress” and “metropolitan improvement.” The animosity toward the private club was striking. The proposal did not advance, but supporters of the road would use similar tactics when it was reintroduced – namely, ignore supporters of the park, attacking instead a club that benefited “the few.”

In 1946, the proposal was once again before the Metropolitan District Commission, now with a bridge at Gerry’s Landing. The bridge was viewed favorably, but opponents of the parkway extension were numerous. Some suggested proceeding with the bridge and then evaluating traffic. Although many people testified to the need for the park and its history, the politicians were aligned, including a young state representative named Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, who claimed that “35 or more persons” had spoken to him in favor of the road. The politicians and planners saw the extension of Memorial Drive as a solution to traffic bottlenecks, and they prevailed. After the road was completed in 1950, the park felt into disuse, as its opponents of the extension predicted. [Images 13, 14, and 15]

The Longfellow Parkland Today

In the 1970s, a step toward reestablishing the lost park was led by Isabella Halsted, a Cantabrigian who grew up when the delta park was full of life. She advocated closing a 1.5-mile stretch Memorial Drive to traffic on Sundays for the enjoyment of pedestrians and cyclists and gave the area a name – Riverbend Park. The proposal became a reality in 1975, and since then, the banks of the Charles are full of people on Sundays, spring through fall, and as of 2021, on Saturdays.

Along with her advocacy for the roadway closing, Mrs. Halsted also created the People for the Riverbend Park Trust for the care and planting of shrubs and flowers from Hawthorn Street to the small triangle near Sparks Street. Over the past 45 years, cleanups and planting by the Trust’s volunteers have contributed greatly to the park’s maintenance. One feature – a playlot surrounded by flowers and overseen by Pat Sekler, a volunteer extraordinaire – is a jewel.

In 2002, the DCR completed a master plan for the Charles River Basin that offered the possibility of some restoration for the park. The plan’s goals for the area between the Anderson and Eliot bridges were to preserve the open character of the banks and the landscape character of the parkway; create a comfortable and safe pathway along the river; and provide safe pedestrian access to the reservation. The plan’s authors recognized the difficulties encountered by pedestrians who seek to cross Memorial Drive. Of note, the plan recommended that the removal of one westbound lane of traffic on Memorial Drive west of Sparks Street in order to widen the parkland and allow better pathways. The report stated that removal of the lane would have minimal impact on traffic due to low peak-traffic volume.

These recommendations were not implemented, but in 2019, the DCR launched a Memorial Drive Greenway improvement project (from the BU Bridge to Eliot Bridge). At the two public meetings that spring, the concept of a road diet received favorable reviews. Some people even called for removing the parkway altogether. Although Covid-19 led to a suspension of project planning, the pandemic underscored the importance of outdoor space in our densely populated city. (When the City Council adopted an open space policy statement in the spring of 2021, observers noted that a comparatively small percentage of public land in Cambridge is used for parks.) When the DCR project holds its next public meeting, the planners will find that Cantabrigians have a greater appreciation for open space than ever. The Longfellow parklands and its companion open space at Gerry’s Landing will be appraised with fresh eyes. Perhaps the DCR project will take us back to the future – to a restoration of Longfellow’s parkland. Its history shows the opportunity.

Sources

Catherine Evans. “Longfellow Memorial Park, 1882–1992,” Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, Volume 1. National Park Service, (1993).

Susan Maycock and Charles Sullivan. Building Old Cambridge. (MIT Press, 2016).

Karl Haglund. Inventing the Charles River. (MIT Press, 2003).

Cambridge Boat Club: A Centennial History. 1909–2009. (2009). [The history describes the club’s move from Hawthorn to Gerry’s Landing and the political wrangling over the extension of Memorial Drive.]

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. Charles River Basin Master Plan (2002). [For background on “Kennedy Park/Longfellow Park” and Memorial Drive between Anderson Bridge and Eliot Bridge, see pp. 132–133.]

Winthrop S. Scudder. “The Longfellow Memorial Association, 1882–1922: An Historical Sketch.” (1922).

Articles from the Cambridge Public Library Collection of Historic Newspapers. (compiled by Annette LaMond, “Longfellow’s Landscape Legacy,” 2021).

Endnotes

1 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Frances Appleton Longfellow, Manuscript, Craigie House, Houghton Library, Harvard University, as quoted in Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for the Longfellow National Historic Site, Volume 1: Site and Existing Conditions, 1993, p. 27.

2 In 1882, a strip of Longfellow land along the future Hawthorn Street from Mt. Auburn to the River became the site of a club for “out-door exercise.” Organized by Ernest Longfellow and several associates, it offered the only landing in the neighborhood for boating and a boathouse, plus five tennis courts and a bowling alley on stilts. The club existed from some 12 years until interest fell off – perhaps due to the condition of the riverfront. With the City’s land-taking in 1894, the club’s boat house and bowling alleys were removed to other sites. In 1897, the bowling alley that was moved to the field owned by Annie Longfellow Thorp became the clubhouse of the Cambridge Skating Club.

3 Susan Maycock and Charles Sullivan describe the politics of parks in Cambridge and the influence of park-making in the larger metropolitan area in Building Old Cambridge (MIT Press, 2016). Although the advocacy for parks had begun elsewhere decades before, some Cambridge leaders were reluctant to use municipal funds for open space. Indeed, a number of Cambridge parks, including the Longfellow Memorial Park, had been created as a result of private generosity.

4 “The Park Report,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XVI, Number 39, 23 December 1893, p. 4.

5 Before the park report, a proposal to extend an electric rail line down Brattle Street had been debated at a series of hearings. See for example, Cambridge Tribune, Volume XIV, Number 40, 19 December 1891, p. 5; Cambridge Chronicle, Volume XLVIII, Number 44, 4 November 1893, p. 1; Cambridge Tribune, Volume XVI, Number 28, 23 September 1893, p. 1.

6 See “The Emerald Metropolis” (Chapter 4) in Karl Haglund, Inventing the Charles River (MIT Press, 2003).

7 The name Charles River Road was changed to Memorial Drive by an act of the state legislature in 1923.

8 Although the park commission considered sea walls for the Longfellow parkland (like those in East Cambridge), Charles Eliot argued in favor of a “natural” landscape. Maycock and Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge, p. 419.

9 Cambridge Park Commission Annual Report, 1896, as quoted in Maycock and Sullivan, p. 420.

10 Maycock and Sullivan, p. 421.

11 Maycock and Sullivan, p. 56.

12 The granite circle was “found,” then excavated and planted by People for Riverbend Park volunteers in the 1990s.

13 According to a 2006 Cambridge Historical Commission study, the Marsh Neighborhood Conservation District contains approximately 147 wood frame residential buildings primarily on Willard, Brown, Sparks, Foster, Lowell, and Mount Auburn Streets. The nearby Half Crown Neighborhood – on the other side of Longfellow Park – was also closely built, though not so closely as the Marsh District.

14 Harris and his family lived on Mercer Circle. A graduate of Harvard, who had taught classics at the College, Harris had a keen sense of community as the foundation of Greek democracy. As a gardener, he appreciated its agrarian roots. For a decade, he devoted himself to the fostering the spirit of community in the Marsh District. Sadly, Professor Harris died unexpectedly in 1923, aged 54. “Prof. W.F. Harris Dies of Pneumonia,” Boston Globe, 15 May 1923, p. 7.

15 In 1897, Mrs. Thorp had rented her Willard Street field to the Cambridge Skating Club for winter use. After the club purchased the property in 1930, it maintained the tradition of children’s gardens. The Willard Street garden continued through World War II, contributing greatly to morale and wellbeing in a time of food rationing. After the war, the gardening ceased, bought to an end by the advent of convenience foods and large grocery stores.

16 The Cambridge newspapers of the time gave considerable information on the organization of the children’s gardening effort on Mrs. Thorp’s field. Here is an excerpt from article that appeared in the spring of 1915:

“Beginning the first of May the land of the Skating Club property will be divided into 125 plots averaging 16×32 feet in size. It is expected that last year’s teacher, Miss Marshall, will have charge of the work daily, while Miss Bartholomew will come to help with experienced suggestions three or four times a week. Each child pays 25 cents for a season’s rental of the land. Seeds are then supplied free and also the use of all the necessary tools. It is expected that the plots will be divided about equally between the boys for vegetables and the girls for flowers. Over 200 children should derive much experience from taking care of these plots which are to be all their own. Many of the children should be able to make five dollars profit from their healthful pleasant work.”

(Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 8, 24 April 1915, p. 9)

A compilation of articles in the Cambridge newspapers underscores the effort of the association’s organizers:

“Summer Gardens for School Children,” Cambridge Chronicle, 4 July 1914, p. 10; “Juvenile Garden Prizes,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVII, Number 32, 10 October 1914, p. 11.“Home Gardens: A New Feature,” Cambridge Chronicle, 24 April 1915, p. 15; “Improvement Association: Longfellow Improvement Association Holds Enthusiastic Meeting—Founded for the Purpose of Improving Mount Auburn Street District—Children’s Gardens on Willard Street and Bathing House on Charles River,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 8, 24 April 1915, p. 9; “A New Association,” Cambridge Chronicle, 1 May 1915, p. 5; “Longfellow Association Meets,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 11, 15 May 1915, p. 5“Garden City Opens,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 13, 29 May 1915, p. 1; “‘Garden City’ for Boys and Girls,” Cambridge Chronicle, 31 July 1915, p. 8; “Children’s Gardens,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 22, 31 July 1915, pp. 1,8; “School Gardens,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 22, 31 July 1915, p. 5.“Neighborhood Celebration,” Cambridge Chronicle, 11 September 1915; “Garden City of 1915,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXXVIII, Number 35, 30 October 1915, p. 4; “Neighborhood Celebration,” Cambridge Chronicle, 9 September 1916, p. 5; School Centre Notes,” Cambridge Chronicle, 30 December 1916, p. 5; “Raise Vegetables,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XL, Number 4, 24 March 1917, p. 1; “The War and Food,” Cambridge Sentinel, Volume XV, Number 35, 31 August 1918, p. 1; “More Land Is Needed for Gardens Here in Cambridge,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XLI, Number 28, 7 September 1918, p. 5; “The Joys of Farming in the City of Cambridge,” Cambridge Chronicle, 20 November 1920, p. 11; “Children’s Garden on Mt. Auburn Street,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XLVI, Number 28, 8 September 1923, p. 6; “City Sponsors 19 Playgrounds,” Cambridge Chronicle, 16 July 1926, p. 14; “Children’s Gardens Win a First Prize,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume LII, Number 28, 14 September 1929, p. 1.

17 “Effort Being Made to Save Small Park on Mt. Auburn St.,” Cambridge Chronicle, 3 October 1930, p.1 (Section B), and “proposed Parkway Threatens Gift of Longfellow Family: Citizens Protest Against Depriving Park of Waterfront—Petition Signed by 585 Residents of the District—Chiefly Frequenters of Recreation Ground,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume LIII, Number 31, 4 October 1930, p. 1.

18 “Meeting of the Longfellow Memorial Association,” Cambridge Tribune, Volume XLIV, Number 47, 28 January 1922, p. 8.

19 “Progress and a Boat House,” Cambridge Sentinel, Volume XXVII, Number 6, 7 February 1931, pp. 1,8; and “A Boat House!” [Editorial], Cambridge Sentinel, Volume XXVII, Number 6, 7 February 1931, p. 8.

20 “Plan to Extend Roadway Through Boat Club Site Is Favored and Opposed: About 100 People Appear at Hearing on Controversial Issue,” Cambridge Chronicle, 14 February 1946, pp. 1,11,13.

20 According to the Trust for Public Land, Cambridge is below the national median in terms of public land used for parks and recreation – 7 percent versus 15 percent. Note the DCR parkland within Cambridge is not included in this calculation.

Photographs

Image 1. View from the second floor of 105 Brattle Street to the Charles River and the Brighton Hills. Drawing by Ernest Longfellow, age 10, dated June 12, 1855. The gardener’s cottage (1846), now 7 Longfellow Park, at the center of the drawing, was moved and remodeled in 1914.

Image 2. Map (ca. 1894) showing the parcels acquired by Longfellow and their division among his two married daughters, Annie Longfellow Thorp and Edith Longfellow Dana, and his sons, Charles A. Longfellow and Ernest W. Longfellow, as well as the land donated to the Longfellow Memorial Association.

Image 3. View from the Longfellow House, ca. 1899. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Image 4. View of Mount Auburn Street, looking east, circa 1887. The dashed area shows Longfellow’s triangular parcel. At its eastern edge is the bowling alley and boathouse of the Cambridge Casino with the gas holder of the Cambridge Gas-Light Company behind. (From “American Architecture” issued in connection with The American Architect and Building News, Boston, Ticknor & Co., 1887)

Image 5. The Charles River Road, lined with London plane trees, just upstream of Boylston (now John F. Kennedy) Street, ca. 1904. The first segment of the river road to be completed, the Cambridge Park Commission considered it an “object lesson” to demonstrate the future appearance of the parkway. Cambridge Park Report, 1905.

Image 6 A & B. Banks of Charles River near Longfellow Park before (1899) and after (1900) improvement. In the mid-1890s, the Cambridge Park Commission began to acquire the riverfront in order to transform its marshes and mudflats into usable land. The building in the photographs is the isolation ward (also know as the “pest house”) of the Cambridge Hospital (later renamed Mount Auburn Hospital), built in 1891. Cambridge Park Report, 1900.

Image 7. Plate 22, “Part of Ward 9, City of Cambridge,” Atlas of the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts. (G.W. Bromley & Co., 1916)

Image 8. Longfellow parkland, looking toward the Cambridge Boat Club, ca. 1910–1920 (likely June or July 1917, according to a notation on the negative). Note the original location of the club was near Hawthorn Street. Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Co. Collection

Image 9. Children’s garden on Mrs. Thorp’s Field, 1915. “‘Garden City’ for Boys and Girls,” Cambridge Chronicle, 31 July 1915, p. 8

Beginning in the mid-1890s – a time of economic hardship, social reformers promoted gardening as a way to improve the economic situation of families. Mrs. Thorp’s land was home to the first children’s community garden in Cambridge. Mrs. Thorp had inherited the property from her father, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who had purchased the field in 1859.

Image 10 A & B. Children’s garden on Mrs. Thorp’s field, ca. 1920s. Annette LaMond, A History of the Cambridge Skating Club (2002)

Image 11. Gerry’s Landing Beach, 1924. The beach was owned by the state, but operated by the City of Cambridge. Cambridge Park Commission Annual Report, 1924–25.

Image 12. Gerry’s Landing Beach, 1935. Archives of the Metropolitan District Commission.

Image 13. View of a lost landscape, now traversed by Gerry’s Landing Road, ca. 1910. This area was seeded with grass in 1899, and remained open until the road was built in 1950. Library of Congress. Detroit Publishing Co.

Image 14. Riverfront Park west of Hawthorn Street before construction of Memorial Drive extension in 1949. The Cambridge Boat Club, visible in the distance was moved to its current location at Gerry’s Landing. Cambridge Historical Commission, Planning Board photo collection.

Image 15. Memorial Drive extension with reduced riverfront park, west of Hawthorn Street, Wednesday, July 15, 2021. Photograph by Annette LaMond

Annette is the historian of two clubs that have connections to the Longfellow parklands – Cambridge Skating Club and the Cambridge Plant & Garden Club. The CP&GC has worked on behalf of the parks and open spaces of Cambridge since the 1920s. Its contributions have ranged from hands-on work, donations for planting and pruning, and advocacy.