Recap – The Basket Club and Mask-Making: The Fabric of Mending in Cambridge

Thu January 1, 1970

Each year, the Cambridge Historical Society chooses a theme for our programs, which we phrase in the form of a question to invite Cantabrigians to come along with us as we explore our collective past. This year we are asking, “How Does Cambridge Mend?” We chose the word “mend” rather than “heal” because, whereas healing often leaves little trace of injury, mending is both a deliberate process and one that allows us to see where the damage was done and how it was repaired. For our first public program of the year on April 1, we looked at the records of Cambridge’s own Basket Club, a women’s community service organization in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries whose members sewed linens for donation to hospitals, orphanages, and other charities in their community. We were also joined by Deputy Superintendent Pauline Wells of the Cambridge Police Department. In the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, when personal protective equipment was in short supply, Cantabrigians from all walks of life sewed tens of thousands of fabric masks and donated them for distribution through the police department. Deputy Superintendent Wells spoke about the impact of the mask drive on police-community relations, and reflected on the connections forged as the city came together to care for one another.

We began our program with a discussion of the Basket Club, whose records are housed at the Cambridge Historical Society. Its founder, Emily Elizabeth Parsons, was born and raised in Cambridge, and served as a nurse during the Civil War. When she returned to Cambridge after the war, she began a campaign to open a hospital, known at first as the Cambridge Hospital. In 1869 she obtained a charter for the hospital to run out of a private residence, but by 1872 it was forced to close due to a lack of funding. It was reopened in 1886, and its name later changed to Mount Auburn, but Parsons did not live to see its reopening, dying of a stroke in 1880. She always believed it would reopen, however, and in 1873 she created the Basket Club to aid in this effort.

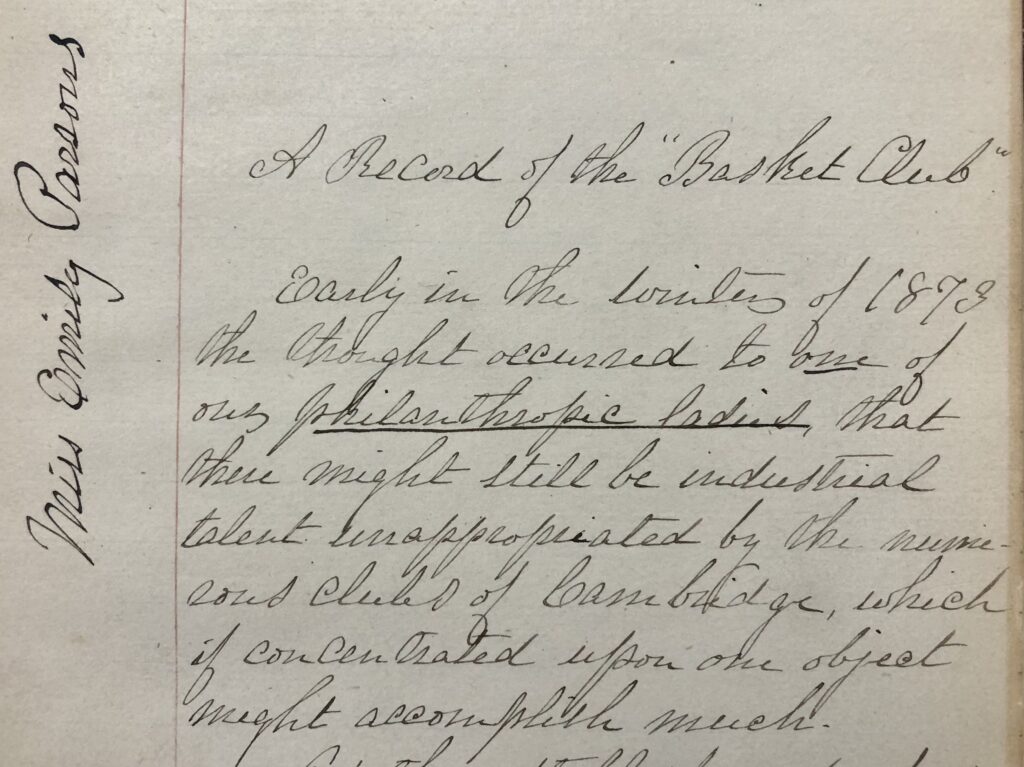

The Basket Club got its name from the large basket of material and sewing supplies that Parsons placed in the middle of her parlor when the club would meet. Its purpose was to sew linens, towels, nightgowns, and other items that would be needed when the hospital reopened. In the first entry in the Club’s records, the club secretary notes that “Early in the winter of 1873 the thought occurred to one of our philanthropic ladies (Miss Emily Parsons) that there might still be industrial talent unappropriated by the numerous clubs of Cambridge, which if concentrated upon one object might accomplish much.”

The ladies met twice a month in the fall, winter, and spring, breaking for the summer, as many were travelling or in residence at their summer homes. Their records indicate that a typical meeting consisted of anywhere from six to sixteen attendees, and that the members took turns hosting the gathering at their houses. They would use their meeting time to sew items for the hospital that was to open and, as time went on, they would also make nightgowns, shirts, dresses, and other items for orphanages such as the Avon Home, as well as for settlement houses and nursing homes, and sometimes directly for donation to the elderly or infirm in their homes. The club records describe the items they made for donation as well-made but simple and unadorned. They also raised funds for these organizations by creating and embroidering items for sale at the numerous charity fairs that took place throughout Cambridge in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – these items were usually household textiles such as placemats, table runners, or quilts, and were often much fancier and more time-consuming than the items for donation.

Of course, the leisure time to attend these meetings, which were held in the afternoons, was only available to women of a certain socioeconomic class who did not need to work outside of the home. The club’s membership was carefully cultivated, and its records reflect instances in which the ladies were eagerly exchanging ideas about whom to invite into the club and how to entice them. The club’s membership was exclusively white and middle- to upper-class, and much of the talk during meetings centered on the latest parties, weddings and trips abroad, as well as analysis of whose house or garden they had visited and how their home design and choice of food and drink measured up to the standards of the day.

But soon after the Club’s founding, the ladies decided that they needed more substantial topics for discussion as they sewed, so they took turns bringing a piece of writing to read aloud while they were working. Their meeting records always include whose turn it was to read at that particular meeting, as well as who was to contribute next. The pieces ranged from poetry by Longfellow to the plays of Shakespeare to philosophical essays by members of the Harvard faculty, as well as religious sermons, travelogues, and newspaper articles. They often discussed current events, including local, national, and international issues. In one meeting the ladies had a heated debate about the candidates for the Cambridge City Council, and at another they lamented the strife brewing in Russia and wondered whether it would lead to civil war. The club therefore not only functioned as a service organization through which members could use their sewing skills to the benefit of those in their community, but also as a place where the women of Cambridge – albeit a limited group of privileged women – could gather to discuss literature, politics, and the important issues of the day. On one issue the members seemed to be of one mind: at one meeting during the leadup to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, all of the attendees agreed heartily that women must be given the right to vote!

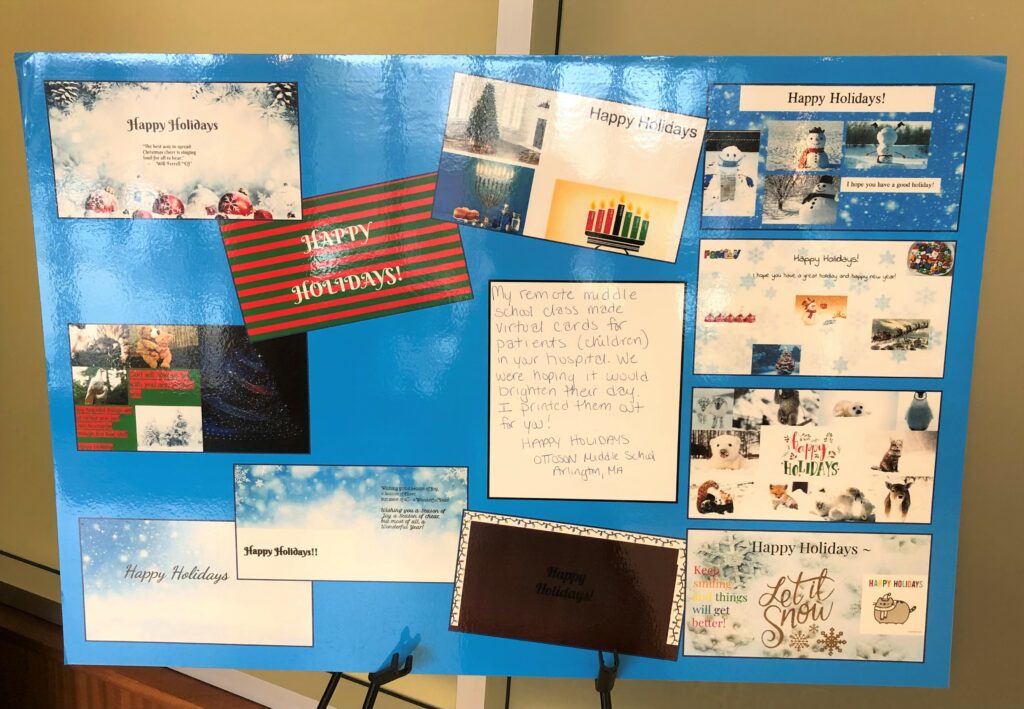

During both the First and the Second World Wars (even before the United States formally entered the conflicts), club discussions often revolved around the war effort, and the Club joined forces with the Cambridge branch of the Red Cross during both wars to knit and sew items for use by soldiers and civilians both at home and abroad. The club saw its membership wane in the years after World War II, and it disbanded for good in 1963, but its legacy remained strong, and obituaries for Cambridge women well into the 1980s and 1990s often mentioned that their subject had been a member of the Basket Club. The appreciation that both donors and recipients felt as a result of the club’s activities is also evident in its record books, which contain copies of cards and letters from grateful community members.

Just as the Basket Club used their sewing skills to aid those in need, so too did many Cantabrigians during the spring and summer of 2020. Deputy Superintendent Pauline Wells described how the Cambridge Police Department, like its counterparts around the country, was struggling to obtain even a fraction of the personal protective equipment needed to keep the community safe. Many Cambridge residents began to create their own fabric masks, and community organizations helped to collect them for distribution through a police-civilian partnership. Residents could pick up donated masks at several walk-in and drive-up locations, and every police officer on patrol was given a supply of masks to give out to those in need. Deputy Superintendent Wells described the overwhelming number of donations, estimating that the police department has given out between 25,000 and 30,000 masks over the past year. She expressed deep appreciation for these and the many other contributions made by community members across the city, and explained how the ability of police officers to connect with the public through the mask distribution effort further strengthened the relationship between police and residents. During a year that was especially fraught with tensions surrounding police-community relations, Deputy Superintendent Wells reflected on the importance of the mask drive as a way to reinforce the fundamental role of the police to protect and serve the people of Cambridge, and she expressed a deep desire to see these bonds persist well beyond the COVID era. “Whatever you need us to do, we’re there for you,” Wells concluded, “because that’s what we’re supposed to do. The police are the community, and the community are the police, and we can coexist in a wonderful, wonderful way.”

You can view the entire program on our YouTube channel: