Who Is Essential Cambridge? Part 2: Teachers

In the first part of our series, “Who Is Essential Cambridge?,” we examined the role of Cambridge women in the industrial sector during and between the World Wars. Women played an important role in industrial production in the years before the outbreak of World War I—a role that continued and intensified over the coming decades. As such, these industrial workers were considered essential to the country’s war efforts, as well as to the development and maintenance of American economic independence and prosperity between and after the wars. In the second part of our series, we explore the role of another group of essential workers: teachers. Although teachers provided a different kind of service to their communities in Cambridge and beyond, these women were considered no less essential to the functioning of American society in the twentieth century. Their role as the shapers of young minds and the “surrogate mothers” to schoolchildren both garnered them the respect and admiration of many, and created a gendered narrative of self-sacrifice that denied women teachers the opportunity to advocate for themselves in the face of low wages and long hours.

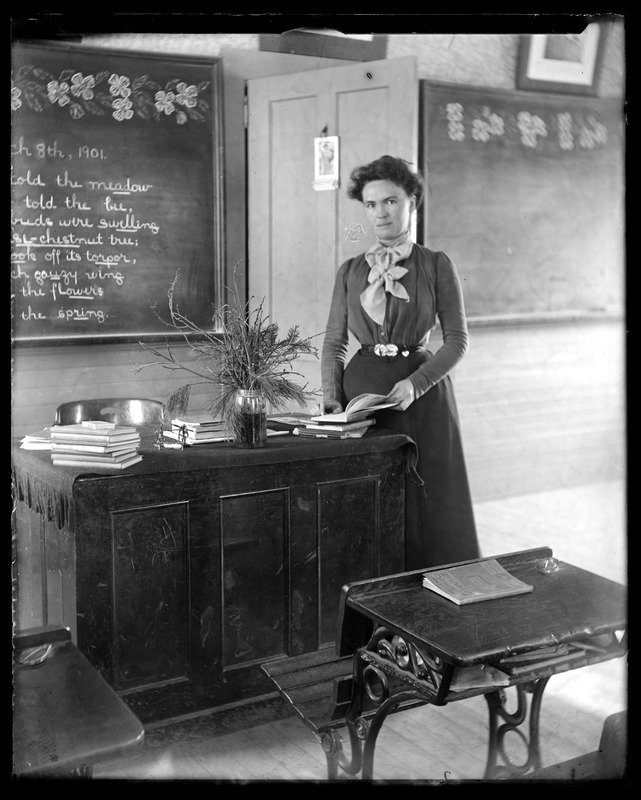

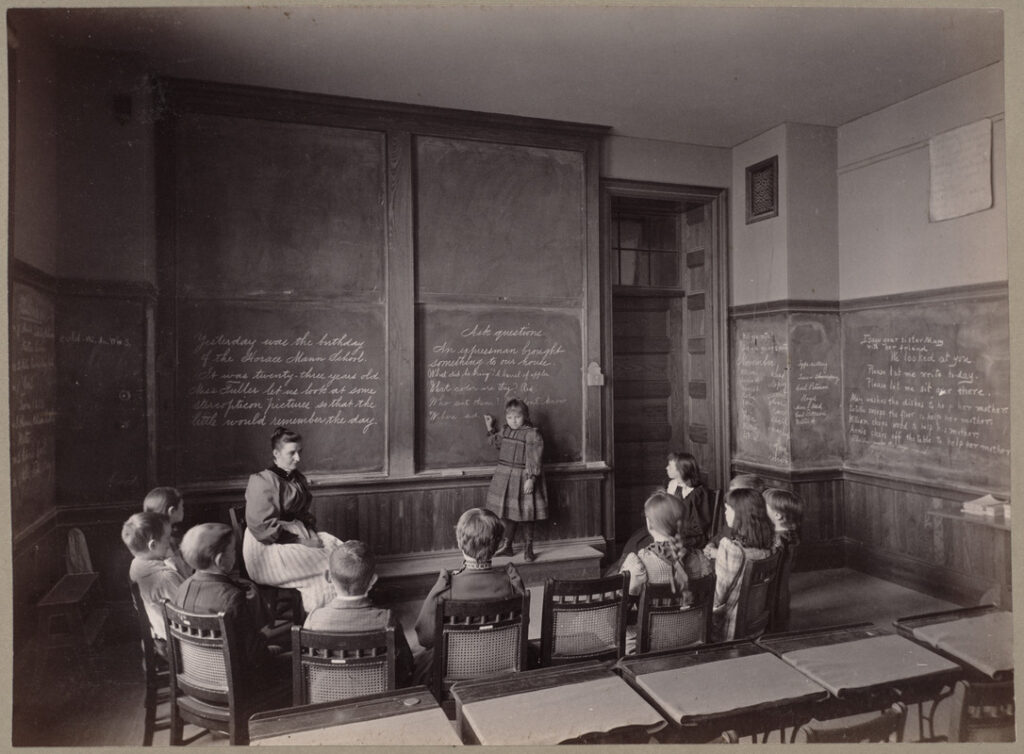

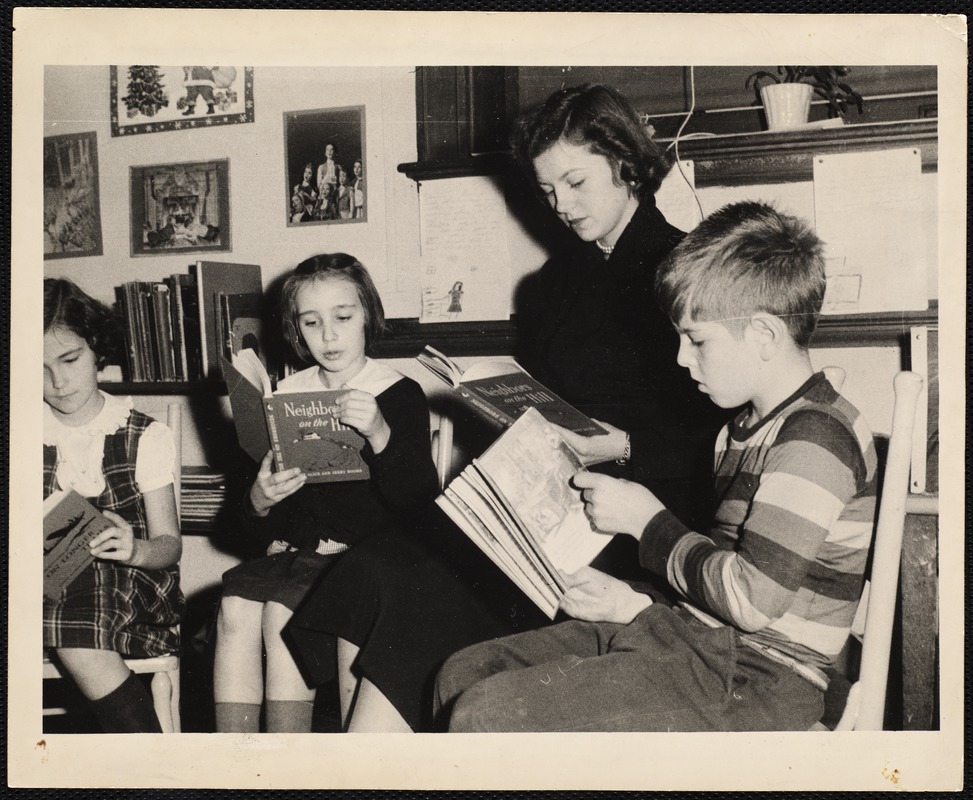

American women have long been responsible for the education of children, both within the household and beyond. In the wake of independence, the concept of Republican motherhood melded the ideas of women’s moral superiority with the need to educate the nation’s youth to become virtuous and informed citizens. Providing instruction in reading, writing, mathematics, history and religion was most often accomplished by women within their households, and was considered an essential element of the duties of a wife and mother. By the early twentieth century—when most formal education had moved outside of the home and into schools—teaching had long been within the purview of women because it was seen as a natural outgrowth of their role as caregivers and nurturers, particularly of young children. Although male teachers were more prevalent at the secondary and college levels, women comprised a majority of elementary school teachers in Cambridge, in keeping with statewide and national trends. As the adult who spent the most waking hours with a child, the teacher was seen as a second mother, caring for children’s emotional needs as well as for their intellectual development. Because working outside the home with other people’s children interfered with the ability to mother one’s own, most teachers were either young women who were not yet married, or older women who had remained single. The perceived lack of personal maternal responsibilities among female teachers fueled the image of the teacher as selfless and self-sacrificing, and led to widespread resistance when teachers petitioned for better wages and working conditions.

Despite the popular perception of women teachers as nurturing caregivers with few or no outside interests or affiliations, Cambridge teachers engaged with issues and causes beyond the scope of their professional lives. A 1916 Boston Globe article reported that the Cambridge School Board “dismissed from the service Miss Madge J. Doherty and Miss Mary J. Smith for ‘pernicious political activity’ in the recent political campaign.”[1] Doherty and Smith had become active supporters of the women’s suffrage movement, and their presence at rallies in support of the Nineteenth Amendment had proved controversial enough to have them removed from their teaching positions. Although we do not have the firsthand perspectives of these two teachers, many women who openly advocated for women’s enfranchisement did so for professional as well as personal reasons; not only did pro-suffrage women see themselves as intellectually equal to their male counterparts, many viewed themselves as morally superior and saw their ability to cast a ballot as a way to safeguard the nation’s ethical wellbeing. Many women teachers saw themselves as the upholders of virtue in society through their work with the upcoming generation, and they considered their participation in the political system a natural outgrowth of their efforts to ensure a morally-sound America.

As was the case with female industrial workers, Cambridge teachers in the 1910s and 1920s were well aware of the strike as a means to achieving improvements in wages and working conditions. In fact, teachers took much of their inspiration from the actions of industrial workers in the late-19th and early 20th centuries and, by the end of World War I, the desire to unionize was strong among the city’s teachers, both male and female. Speaking to a group of Cambridge teachers in 1919, American Federation of Teachers president Charles Stillman declared, “Teachers need a union badly. They want cooperation, freedom of speech and many other objectives besides salary. Labor has always helped the teachers. They did it here in Cambridge a few years ago when the teachers came to them with a referendum on their bill to the legislature on salary. Cambridge teachers know this and appreciate their help.”[2] Over the next decade, the issue of teachers’ working conditions and their desire to unionize would continue to be a contentious and well-publicized issue, both in Cambridge and across the Commonwealth. In a 1919 article supporting unionization, a reporter for the Cambridge Tribune argued that,

[t]here is at present on foot a movement to obtain ‘justice for the foster-parents of our children’….There is no class of workers of which we demand so much. We commit into their keeping the minds, the bodies, and the very souls of our children in the tender and formative years of their lives, and they, receiving these children, can indeed be said to hold in the hollow of their hands the future of America….They have received little honor and somewhat less of pay….The teachers have no spokesman, however, to demand even the simple justice of a living wage, so to them we give their petty prewar pittance, so meager, so pitifully inadequate, that it places a burning brand of shame and disgrace upon this nation.[3]

The reporter concluded that “[a]s long as we refrain from giving the school teachers a living wage, we are absolutely prohibited from calling ourselves either just or honest.”[4]

Although many sectors of society expressed their support for teachers’ efforts to improve their situation, some expressed doubt that such efforts would ultimately result in a strike. Speaking at the First Universalist Church in Cambridge, Charles Parmenter, master of Boston’s Mechanic Arts High School, declared that “[t]eachers expect to make sacrifices; they do not expect to be martyrs.”[5] He went on to say, however, that a strike is not to be expected, but that a more gradual exodus will leave Cambridge schools in peril:

Teachers in no community will strike. They are absolutely helpless. But what they will do is this: they will quietly leave the work one by one, and those who go first will be the best. It always happens so, and by and by when the community wakes up to the fact that it must pay a very much higher salary in order to command higher ability communities will find themselves with their schools manned with inferiority, and we know that inferiority seldom dies and never resigns.[6]

Other Cantabrigians agreed that the quality of teaching could be directly tied to teacher compensation, but not all believed that an increase in salary was feasible or even necessary. In 1920, Cambridge Mayor Edward Quinn claimed that “We are doing our best as regards teachers’ salaries,”[7] while, at the same meeting, School Committee member Mary Winslow expressed support for a new rule enacted by the Committee “by which the teachers must reach to a higher standard. This rule ought to make our Cambridge girls, who in a way feel that the [city’s teaching] positions belong to them, more ambitious.”[8] James Cassidy, another member of the School Committee, voiced his concern about a potential teachers’ union and its similarities to organized labor, asking “Would they follow the labor program, demand what you want and get it? Labor men are very materialistic. Will the teachers with the same amount of power be likely to act likewise?” Responding to Cassidy’s inquiry, Harvard professor of education Paul Hanus encapsulated the teacher-as-martyr stereotype, declaring:

[W]hile organized teachers are a real danger, yet the situation is not to be compared to that of organized labor for the teachers are not working solely for a living as the laboring men are. Teachers have selected teaching as a profession. They have a different attitude toward the work they render than do members of labor organizations. A teacher has a clearer view of his responsibility than has the ordinary wage earner. It is a moderate danger compared to what faces us with organized labor. A teacher will consider the higher welfare of those with whom he has to deal rather than his own material welfare.[9]

Because teachers were considered both essential to the growth and instruction of children and selflessly dedicated to their profession, their efforts to organize and advocate for better conditions were downplayed by many who believed that they could not or would not take direct labor actions.

But despite these assumptions about the self-sacrificing nature of the teaching profession, Cambridge’s women teachers both noticed and resented the discrepancy between their salaries and those of their male counterparts. In a 1922 article, the Cambridge Sentinel reported that the School Committee had received four petitions “for adjustment of salary scales of the women teachers of the High Schools and grammar school masters, the prevocational schoolteachers and the continuation schoolteachers….The High School teachers ask an increase of $5200 to equalize the greater increase recently received by the men teachers than by the women.”[10] Although these petitions were tabled, a Cambridge Chronicle report from 1923 states that the Committee “voted to increase the salaries of the women teachers at the High and Latin school $180 a year and the salaries of the elementary school teachers $102 a year in accordance with the schedule submitted by City Auditor Thurston and recommended by Superintendent Fitzgerald.”[11] Despite these pay raises, however, women teachers were still earning less than their male coworkers performing the same duties in the same schools. Because of this ongoing disparity in wages, female teachers in Cambridge decided to create their own organization to advocate for themselves in matters of compensation. By 1926, they had founded the Cambridge Women Teachers’ Organization (CWTO) and were debating about whether or not to unionize. The Boston Globe characterized the organization’s origins as the “considerable agitation over the alleged ‘unfair treatment’ by the School Committee and the high school men teachers whom [the CWTO] accuse of ‘double-crossing them.’”[12] Speaking at a meeting at Malta Hall, a spokeswoman for the women teachers stated that “[w]e wish to organize because, with the backing of the national federation behind us, we may protest against last Spring’s pay raise. At that time the Cambridge School Committee granted such unequal pay raises that the ratio between the pay of the men and the women teachers was more unfavorable to the women than before the raises were made.”[13]

Indeed, the differential between male and female teachers continued to be a contentious issue in Cambridge in the years to come. In 1927, School Committee member James Cassidy claimed that “the only question with the women was the differential and that they would be perfectly satisfied if the men’s salaries were reduced.”[14] According to a report by the Cambridge Federation of Teachers,

[T]he original differential between the men and women was $552; in June, 1926, it was increased to $749, an advance of $194, in the high school. The original differential between masters and women teachers in the elementary schools was $1796; in June, 1926, it was increased to $1,946, an increase of $150. The original difference between elementary teachers and kindergarteners was $24; in June it increased to $124, an advance of $100.[15]

The same year, Mayor Quinn endeavored to solve the problem of gender-based wage discrepancy by proposing an amendment to have only women teachers appointed to the city’s elementary schools – a proposal that Quinn eventually withdrew due to lack of support from both teachers and the School Committee. Clearly these gendered differences in pay, along with the low wages for teachers overall, proved significant enough that women teachers would continue to bring it to the attention of the Superintendent and the School Committee for years to come, albeit with little resolution.

World War II introduced new challenges to women teachers in Cambridge and beyond as shifts in the labor force led Americans to rethink the nature of essential work. A 1943 report in the Cambridge Sentinel cited a Massachusetts state survey showing a shortage of teachers and predicting that “[t]here will be about 500 graduates of our teachers colleges to fill approximately 2000 vacancies in our schools.”[16] The report attributed the shortage to the large number of teachers who have left the profession in order to join the armed services or engage in other types of war work. It also emphasized the essential nature of teaching, especially in wartime, calling schools “the bulwarks of American freedom [that] have provided a background for the heroic endeavors of our armed forces which are such a pride to us all.”[17] Framing the education of children as a specifically female responsibility, the report encouraged the young women of Massachusetts to consider teaching not only as a noble profession but also as their patriotic duty:

A young woman who graduated from high school this year can give most important national service by training for teaching. It is war work of the highest type. Carrying on and preserving our traditions of American freedom. In peace and in war this is an essential patriotic service….Our young men are called upon to defend our country and the front. Is there any finer service that a young woman can render to her State and to her Nation than to train for a teaching career, so that she may take her place in the army of teachers who have maintained and will maintain the high traditions of opportunity in a free democratic America. The young women of our high school graduating classes are urged to consider this as a real war effort and a national service of the highest value.[18]

Thus the moral responsibility of serving as “surrogate mothers” to their students becomes conflated in wartime with patriotism and national service as well as individual self-sacrifice. In the teaching profession, as with industrial work, America’s involvement in war superseded calls for unionization, strikes, and other organized labor actions as nationalism rather than individualism rose to the forefront of American consciousness.

Once the war was over, however, Cambridge teachers renewed their advocacy efforts for equal pay and better treatment. One issue that female teachers were keen to address was the 1945 School Committee rule stating “that women teachers married since April 21, 1942, would have their services terminate 60 days after the discharge of their husbands from the armed forces, if they had been placed on the inactive list and provided they were able to resume full-time employment.”[19] In debating this proposal prior to its enactment, School Committee members were divided over its merits, with many concerned about the potential effects of dual-income families on the ability of single women to earn a living. School Committee member James Cassidy predicted that “[t]his will open up a wide road, we’ll get 100 applications in two weeks, both husband and wife getting salaries. What about the Normal School girls waiting for positions?”[20] By framing the debate in this way, Cassidy and other opponents of married women teachers pitted women against each other in a perceived battle for limited positions and salaries; if a married woman filled a teaching position, she was “robbing” a single woman of much-needed income. Although it may not have been their intent, the rhetoric employed by supporters of a one-income household resulted in a further schism within the ranks of Cambridge’s female teachers, who had already been divided from their male counterparts for decades over the issue of gender-based wage disparity.

Two years after the end of World War II, Cambridge voters finally made the decision to grant equal pay to the city’s male and female teachers. In an article highlighting the upcoming referendum, the Cambridge Sentinel declared that “no greater problem in public education exists today than that of retaining qualified teachers and encouraging young people to choose teaching as a career. For this reason [The Cambridge Citizens’ Committee] are cooperating with the Women Teachers Club of High and Latin School in supporting the referendum which will appear on the ballot.”[21] By 1947, over 200 of the 351 cities and towns in Massachusetts had already enacted legislation ensuring equal pay for men and women teachers, making Cambridge among the later cities to do so. Although gendered salary differences were no longer codified in city law, broader societal forces continued to circumscribe the lives and livelihoods of female teachers for decades to come. As married women with children began to make up a larger proportion of teachers, their continuing need to balance paid and unpaid labor meant that many chose to teach at the elementary school level in order to align their schedules with those of their own children. Working within a system that assigned (and continues to assign) both greater prestige and higher wages to secondary education, as elementary school teachers women still made less money and filled far fewer administrative positions than their male peers, who were not nearly as encumbered by domestic responsibilities. As the stereotype of teachers as nurturing caregivers and “second mothers” persisted, their ability to organize and demand better working conditions was either downplayed or vilified as a betrayal of the selfless dedication expected of them. Although the past seventy years have seen several near-impasses, the teachers of Cambridge have not declared a formal strike despite resurgent unrest over pay, benefits, and hours. Still considered essential—more so than ever during the era of COVID-19 and remote learning—Cambridge’s women teachers continue to shoulder the mantle of respect for their professional dedication while juggling the demands of paid and unpaid labor within their own families.

In the next installment of our series, we will explore the role of Cambridge women in another profession lauded for its members’ self-sacrifice: nursing. As with teaching, women were considered a natural fit for nursing because it was seen as an extension of their unpaid caregiving role within the household. Whether as a paid professional or as a member of a religious order, the nurse was expected to sacrifice her own economic, social, and even physical wellbeing in order to care for her patients. Cambridge’s wealth of medical institutions made the city a center for nursing, and our next post will examine the ways in which the city’s nurses balanced caregiving responsibilities within and outside of the home and family.

[1] “No More Removals of Teachers Likely,” Boston Globe, January 12, 1916, p. 11.

[2] “Federation Head Speaks to Cambridge School Teachers,” Cambridge Chronicle, May 17, 1919.

[3] “Justice for the Teachers,” Cambridge Tribune, June 7, 1919.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Chas. W. Parmenter Speaks About Teachers’ Salaries,” Cambridge Chronicle, November 18, 1919.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Cambridge Schools Under Discussion,” Cambridge Chronicle, March 20, 1918.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “The Salary Question,” Cambridge Sentinel, March 18, 1922.

[11] “School Board Recommends Increase in Salaries of Women Teachers,” Cambridge Chronicle, June 16, 1923.

[12] “Cambridge Teachers Delay Union Action,” Boston Globe, November 23, 1926, p. 11.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Women Teachers Renew Requests About Salaries,” Cambridge Tribune, April 16, 1927.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Teacher Shortage – An Emergency,” Cambridge Sentinel, March 20, 1943.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Married Women Teachers Return to Their Jobs,” Cambridge Sentinel, March 9, 1946.

[20] “School Board Delays Action on Married Teacher Proposal,” Cambridge Sentinel, January 24, 1942.

[21] “Referendum,” Cambridge Sentinel, November 1, 1947.