‘Changing Tides in Cambridge Industry’ talk will examine wave of labor and immigration

By Beth Folsom, 2022

Since its beginnings as a colonial settlement, Cambridge has seen numerous shifts in its population, as waves of migrants arrived from various parts of the United States and around the world. As these new Cantabrigians arrived in the city needing work, many found jobs in the city’s industrial sector, most notably in the glass, brick, furniture, meatpacking and confectionary factories in Cambridge. Employment in many of these industries was dominated by different immigrant groups at different periods, with newer arrivals taking jobs in lower-paying, more physically demanding sectors. Eventually these ethnic groups would move up the socioeconomic ladder, finding employment in more lucrative and less strenuous industries while the next wave of newcomers replaced them. For many, similar work experience at home and the recommendation of friends, family or others of their same ethnicity led them to choose a particular industry. For others, their status as immigrants drastically limited the employment options open to them. Whether by choice or circumscription, the clustering of migrant groups in particular industries helped shape the labor landscape of Cambridge.

History Cambridge explores the ties between immigration and industry in a History Café, “Changing Tides in Cambridge Industry,” taking place at 7 tonight. (Update on May 23, 2022: This talk is delayed by illness.) We will be joined by Andrew Robichaud, professor of history at Boston University, to discuss the various migrant groups who played crucial roles in the development of the city’s industrial sector.

Between 1810 and 1900, the population of Cambridge went from just 2,000 to more than 90,000, many of them migrants from abroad or from other parts of the United States. Among the earliest arrivals of this period were Germans and Scots, many of whom took jobs in the city’s glass factories and in the confectionary industry. By the mid-19th century, the Potato Famine had devastated much of rural Ireland and driven many Irish to seek refuge in America. Many of the new Irish arrivals during this period were employed in the brick making and meatpacking plants of North and East Cambridge, doing the arduous work that native-born Cantabrigians refused, often working long hours for low wages.

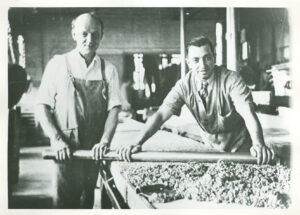

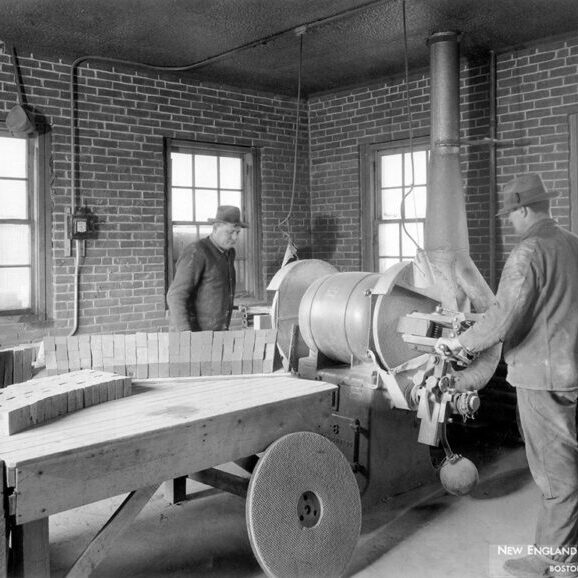

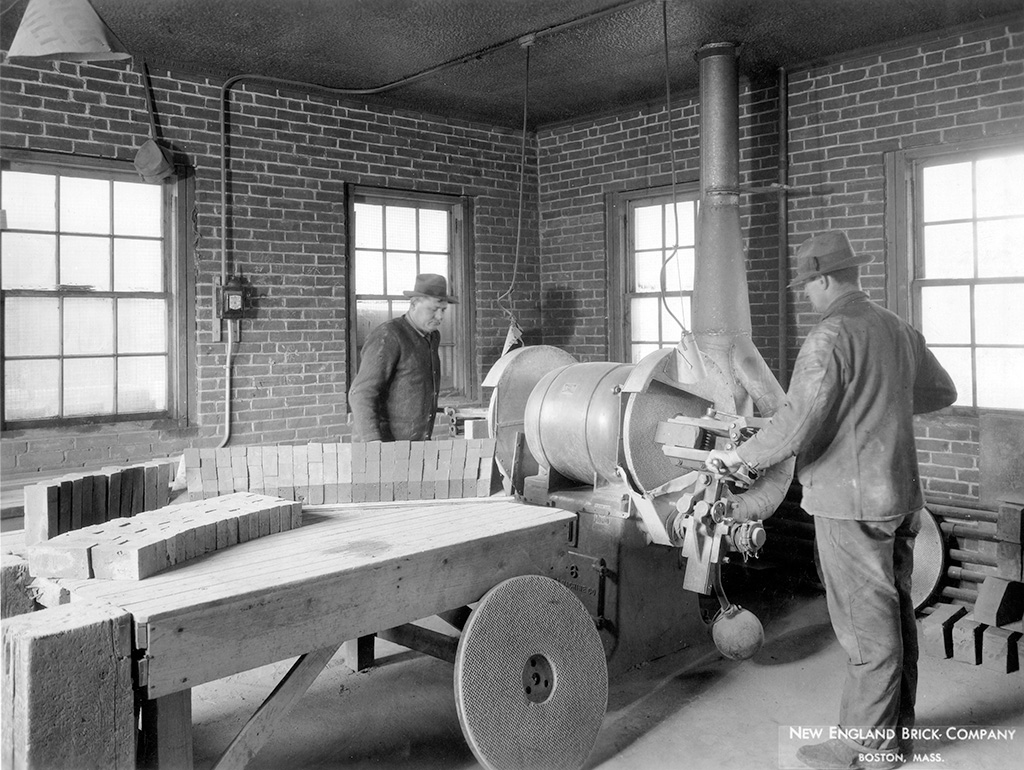

Brick making in particular was a quickly growing industry in North Cambridge; the area’s clay pits helped to meet increasing demand for a building material that was sturdy and impervious to the coal fires that posed a significant risk to wooden structures. Irish immigrants so dominated the clay pit and brickyard workforces and the residential area that surrounded them in the mid-1800s that this section of North Cambridge became known as “Little Dublin.” By the 1870s, however, many of the Irish workers had gone on to other kinds of work, and their place in the brick making industry was taken by new French Canadian arrivals. Although both groups shared a Roman Catholic religious affiliation, the Irish – many of whom had been in Cambridge for several decades – did not welcome the French Canadians, but instead sought to distance themselves from the new arrivals.

It was not just immigrants from abroad who changed the composition of Cambridge’s workforce during the 19th and 20th centuries; Black Americans from the South began arriving in Cambridge after the Civil War, with many more coming during the Great Migration (1915-1970). These Black migrants took jobs in the meatpacking, metalworking and furniture factories upon their arrival, as well as laboring as garment workers and candy makers. The presence of so many Black workers in confectionery factories is especially symbolic because the origins of this industry are so deeply enmeshed with the city’s ties to sugar plantations in the Caribbean during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Many of Cambridge’s most wealthy residents made their fortunes through enslaving Black workers on these plantations, and the elegant houses of areas such as Tory Row were built with the profits of slavery (and, in some cases, by the hands of those who were enslaved by these same families on their Cambridge properties).

Whether arriving from abroad or other areas of the country, the waves of migrants who flooded into Cambridge over the past two centuries have helped shape the character of the city and its industrial sector. The presence of a multitude of ethnicities has had a profound effect on what Cambridge has produced and how, as well as on the residential areas where these workers lived, played, worshiped and engaged in everyday life. We look forward to exploring the connections between ethnicity and industry, and we hope you will join us at our History Café. This virtual program is free, but registration is required. If you miss the event, be sure to check our YouTube channel in the coming weeks for video of the event.

This program is made possible by Mass Humanities, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and you. Thank you!

Beth Folsom is program manager for History Cambridge.

This article was originally published in our “Did You Know?” column in Cambridge Day.