Cars in Cambridge by Doug Brown

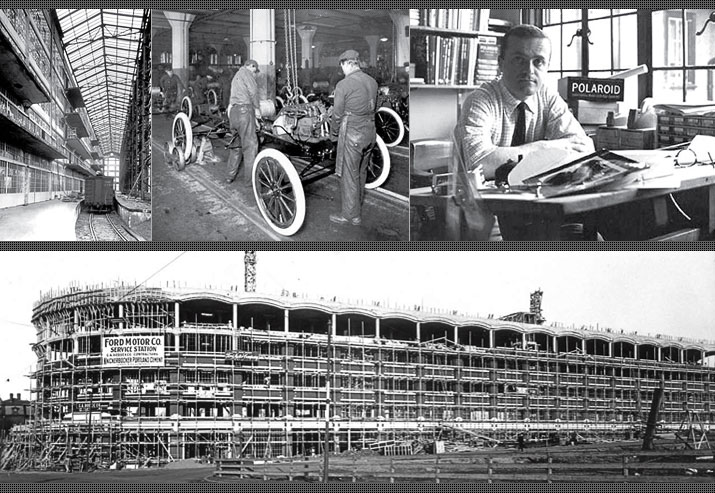

Top Left: Ford’s Cambridge Assembly’s central hall; parts arrived by rail from Ford’s plant at Highland Park, Michigan. In early years, branch assembly plants like Cambridge averaged just 10 cars per day. Top Middle: Assembly– line workers mate an engine and chassis together at Ford’s Model T plant at Highland Park in 1913, the year before the Cambridge Assembly opened. Top Right: Polaroid was a later occupant of the five– story Ford building and used it for manufacturing. Bottom: The Cambridge Assembly plant under construction in 1913. Beginning in 1910, Henry Ford built Model T plants throughout the country; assembling cars near regional markets greatly reduced shipping costs. All photos courtesy of Ford Motor Company Archives and the Cambridge Historical Commission

With air bags, anti–lock brakes, traction control, and GPS, the Uber driver of today operates a very different machine from the family chauffeur’s open–topped horseless carriage of 100 years ago. But regardless of the generation, Cantabrigians have always loved working on cars. Today that tinkering is just as likely to occur in a university lab as in a backyard garage.

First among the former is the Sloan Automotive Lab, founded at MIT in 1929 by Professor Charles Fayette “Fay” Taylor with the goal of being the premiere automotive research lab in the world. At last count, the lab had produced more than 600 scientific publications. Professor Taylor’s funding originally came from Alfred Sloan, the CEO of General Motors. Today, the lab’s work is supported by GM, Ford, Toyota, VW, Volvo, Ferrari, among many other automakers.

Taylor was a legendary figure in the field of engines, working for the Wright brothers and helping design the fuel–efficient engine for Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. He directed MIT’s lab for 31 years and died in 1996 at the age of 102. His two–volume work, The Internal Combustion Engine in Theory and Practice, remains a seminal reference for automotive engineers.

MIT also produced a couple of graduates, Tom and Ray Magliozzi, who have done their share to spread the car gospel far and wide. The university continues to pioneer research on fuel efficiency, emissions reduction, solar electric vehicles, and self–driving cars. The CityCar, a foldable, stackable urban electric vehicle, was created by the late Bill Mitchell, a dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning. A team of five MIT graduates designed the Transition, a street–legal “flying car” soon to begin production at Terrafugia in Woburn.

But these innovations are only the latest evidence of the region’s ground–breaking automotive work, which goes back almost to the beginning of the automobile’s history. Billy Durant, legendary rags–to–riches–to–rags founder of GM, was born in Boston in 1861. In 1893, Charles and Frank Duryea built and road– tested the first gasoline–powered American car in Springfield. The very first license plate in America, Massachusetts “1,” was issued on September 1, 1903, to Brookline’s Frederick Tudor, a descendant of Cambridge ice baron Frederic Tudor. (A later descendant still holds the plate.) And from 1893 through 1989, some sources claim that Massachusetts produced more cars at its assembly plants in Cambridge, Somerville, Springfield, and Framingham than did Detroit, with the state’s factories turning out Knox fi re trucks, Indian motorcycles, Pontiac GTOs, Packards, Rolls– Royces, GMs, Fords, and many lesser–known brands.

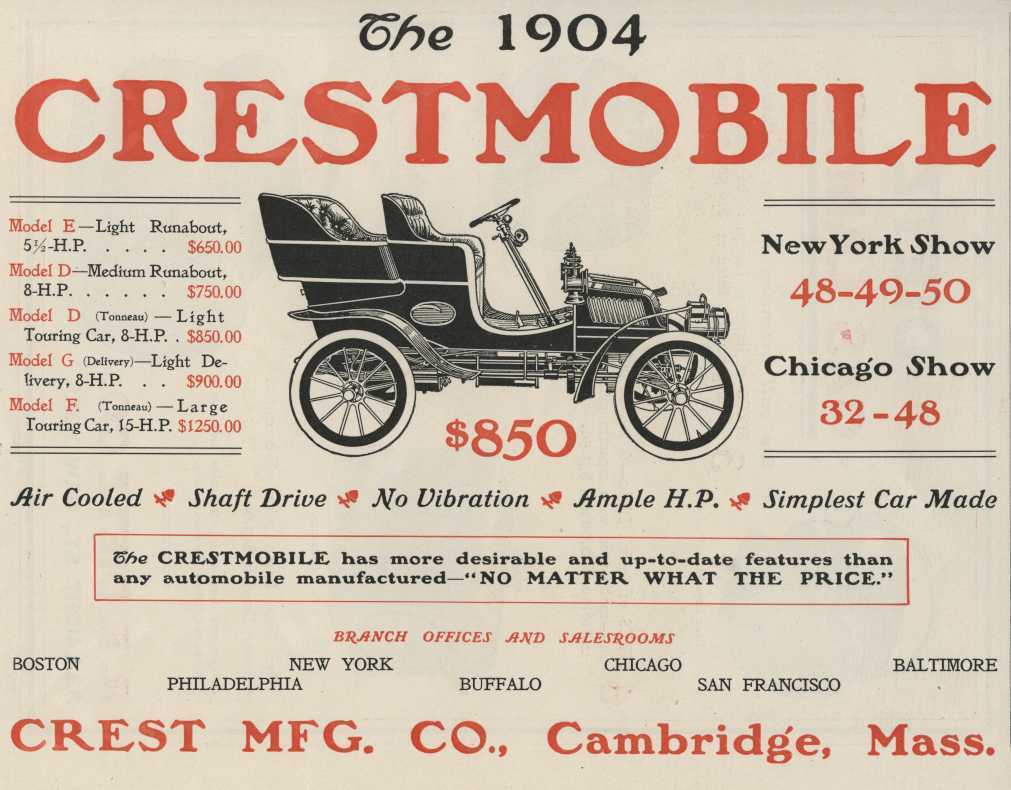

An advertisement for the 1904 Crestmobile. That year, the East Cambridge company employed 300 workers producing five cars per day. Photo courtesy of eBay

Locally, the Ford Motor Company opened its cutting–edge Cambridge Assembly factory at the corner of Brookline Street and Memorial Drive in 1913. It was the first vertically integrated assembly line in the world, with cars, including the famous Model T, moving through an assembly process spanning five stories. It was replaced in 1926 by the Somerville Assembly, an even more massive 145–acre affair that closed in 1958, following the failure of the Ford Edsel. The site is now the recently completed Assembly Row mixed–use development. In later years, the Cambridge plant has been used by Polaroid and Pfizer and is now owned by MIT, which leases gleaming lab space to life science tenants.

Nationally, there were over 1,800 automobile manufacturers in the United States from 1896 to 1930. Very few survived. Besides Ford, two other brands of the early 1900s are associated with Cambridge: the Berkshire Motors Company and the Crest Manufacturing Company. Berkshire Motors was founded in Pittsfield in 1905. It moved to Cambridge in 1912 and was renamed Belcher Engineering before closing in 1913. Only 150 cars are known to have been produced.

Crest was more successful, though it didn’t last long either. Between 1901 and 1904, it built several versions of its Crestmobile, a one–cylinder car producing between 3.5 and 15 horsepower, at a factory near the current site of the Garment District in Kendall Square. Each year, the company introduced new models with ever–improving capabilities, including touring cars, delivery vehicles, and a “doctor’s runabout.” An ad in Automobile magazine claimed that “a comparison of the 1903 Crestmobile with any other low–priced car will prove it superior in every detail.” The company even provided a removable gas tank that “will appeal to the tourist when occasion comes to store vehicles where objection to gasoline is made on account of insurance rules.” Cars sold for between $600 and $1,250 were capable of speeds up to 30 mph, and, unlike the vehicles pioneered by Henry Ford, were available in two colors: red or green. The company was eventually sold to automaker Alden Sampson in 1905 and moved to Pittsfield. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions, Alden Sampson ultimately became part of the Chrysler Corporation.

Local automakers were not the only ones hoping to capitalize on the exploding American market—the city had a healthy auto parts industry as well. A survey of period business directories finds companies making springs, running boards, auto accessories, electrical equipment, and rubber goods. The Blake Spark Plug Company manufactured its revolutionary Quick Detachable Spark Plug at a factory at 101 Concord Avenue, now the site of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics on Observatory Hill. The Prest–O–Lite Company, producer of the first truly effective automobile headlight, built an acetylene plant in West Cambridge in 1920 to provide fuel for its products. Prest–O–Lite was eventually folded into the Union Carbide Corporation, and the site at Fresh Pond was redeveloped in 1962 into the Fresh Pond Mall, the ultimate expression of mid–20th– century, car–centric urban design.

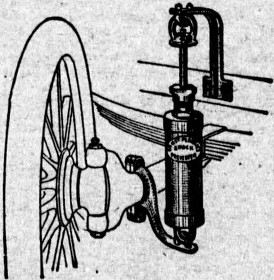

Ernst Flentje’s “automatic hydraulic jounce and recoil preventer,” perhaps the first modern shock absorber. Company advertisements modestly described these shocks as the “Best in the World.” Photo courtesy of the Cambridge Chronicle, May 6, 1911

But of all the Cambridge auto manufacturers, perhaps the greatest self– promoter was Ernst Flentje, a German immigrant and sausage importer who lived at 1643 Cambridge Street, directly across the street from what is now the Cambridge Rindge & Latin School (and next door to the home of the great 19th–century baseball pitcher Tim Keefe at 1653 Cambridge Street). Flentje, who was also a real–estate investor, first came to the public’s attention in a story on the front page of the February 6, 1907, edition of the New York Times. While vacationing in Florida, the paper reported, “Mr. and Mrs. Ernst Flentje of Cambridge, Mass., were dumped into the New River in their automobile late yesterday afternoon, at Fort Lauderdale, but escaped with their lives.” On his return to Cambridge, Flentje designed and began producing “The Flentje,” an “automatic hydraulic jounce and recoil preventer”—a shock absorber. Though it is uncertain whether his brush with a watery death inspired his subsequent endeavors, the rest of his life was devoted to improving the safety and performance of the automobile.

Flentje went on to receive seven patents for shock absorber improvements between 1908 and 1925. In his first two years in business, he sold 5,000 units. By 1916, things were so good that his stable was converted into a full–fledged factory facing Trowbridge Street. In a 1912 ad, the company claimed that its product was the “Best in the World” and offered $5,000 to any other shock absorber manufacturer to disprove the claim. “Try a set on thirty days’ free trial and three years’ guarantee,” Flentje said, “and be convinced of the correctness of my claims.”

Today, though his home on Cambridge Street is long gone, evidence of this pioneer’s place in Cambridge history lives on in the Ernst Flentje House, at 129 Magazine Street. Originally built in 1866 as a Second Empire single–family residence with a mansard roof, it was restyled in 1900 by Flentje and converted into a three–unit apartment building (Flentje also owned the building next door, 131 Magazine Street). The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983 and, according to the Massachusetts Historical Commission, remains “one of the most exuberantly decorated triple deckers in the city.” Meanwhile, the factory he built in the stable behind his home on Cambridge Street is now the home of the Cambridge–Ellis School.

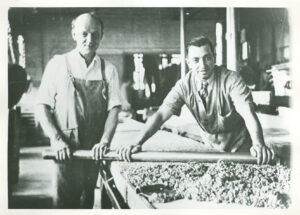

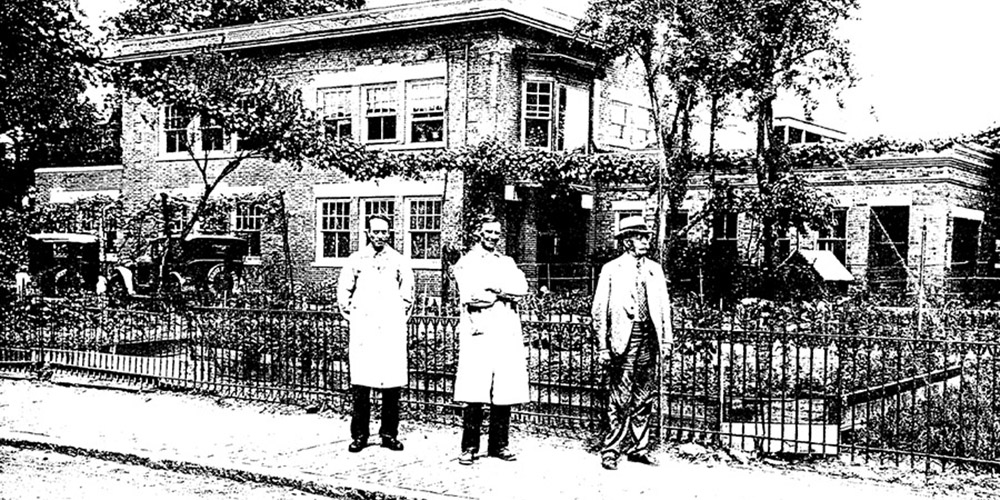

Ernst Flentje (center) and colleagues in front of his factory on Trowbridge Street, now the site of the Cambridge-Ellis School. Photo courtesy of the Cambridge-Ellis School archives