Thanksgiving in Civil War Cambridge

By Beth Folsom, 2021

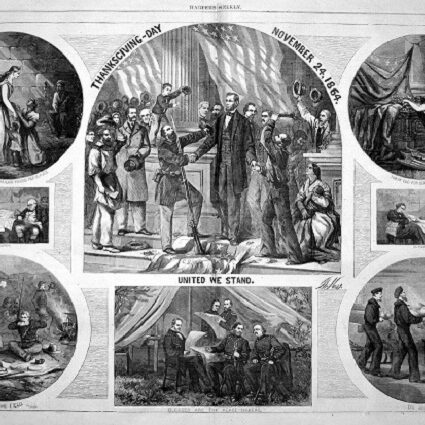

From the beginnings of English settlement in the American colonies, both religious and secular leaders called for certain days to be set aside for fasting, prayer and thanksgiving, usually aligned with the change in seasons and their accompanying times of planting and harvesting. The earliest settlers to arrive in Massachusetts brought this tradition with them from England, and what we now think of as “the first Thanksgiving” was actually part of a long legacy of thanking God for the abundance of the natural world and the gift of Divine favor on human enterprise. During the colonial and early national periods, such feast days were proclaimed at the local, colonial or state level; it was not until 1863, at the height of the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln called for a national day of thanksgiving (and it would be half-century before an act of Congress made the fourth Thursday in November a permanent national Thanksgiving holiday).

In Cambridge, as in much of New England, the story of the “Pilgrim Fathers” loomed large in the popular imagination, and the city’s celebrations of a statewide Thanksgiving Day in the 1860s often referenced the harvest feast that the new arrivals to Plymouth shared with the Wampanoags on whose land they had imposed themselves. By 1860, Thanksgiving had become a symbol of family togetherness and gratitude for the bounty of both agriculture and industry. It was also a time when those who had been blessed with plenty (or at least enough to satisfy their needs) were called upon to extend aid to those less fortunate through donations of food, clothing, and money. In both its emphasis on family unity and charitable giving, Thanksgiving in Massachusetts was a more prominent holiday even than Christmas, which the Puritan disdain for its pagan roots had kept as a relatively minor celebration compared to other areas of British America.

At Thanksgiving in 1860, Cambridge residents had an additional reason to be thankful: the recent election of Abraham Lincoln as President and Republican control of Congress, which Northerners felt sure would remedy the sectional divides that had long been rending the national fabric. In his “Proclamation for a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Praise” of November, 1860, Massachusetts Governor Nathaniel Banks declared that the public give thanks “especially for the inestimable privileges of Republican Institutions of Government,” and “[f]or the preservation of the States united.”1 These sentiments were widely echoed in Cambridge, with a notice in the Cambridge Chronicle announcing that “Thanksgiving services on account of the great national triumph of Liberty, will be held at the Harvard St. M.E. Church next Sabbath evening, commencing at 7 o’clock. Sermon by the Pastor. Subject: The Cause and the Consequences of the Election of Abraham Lincoln.”2

By November of 1861, the nation was embroiled in a civil war, and the public discourse at that year’s Thanksgiving focused on the “vacant chairs” that sat at many of Cambridge’s dinner tables, their usual occupants away at the front or lost in battle. As the sectional crisis exploded into war, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew invoked the legacy of the first Thanksgiving in his annual proclamation, noting that the day appointed was “the anniversary of that day, in the year of our Lord sixteen hundred and twenty, on which the Pilgrims of Massachusetts, on board the Mayflower, united themselves in a solemn and written compact of government.”3 In a time of such upheaval and discord, leaders like Andrew looked to the example of the Mayflower Compact to center New England history and values in the nation’s creation narrative, lauding the tale of a diverse group of immigrants pledging loyalty and cooperation to one another just before their arrival in America. The Pilgrim story would be referenced again and again in the coming decades as the country experienced and attempted to heal from the sectional divisions of the Civil War.

During the war itself, Cantabrigians took great pains to collect and send food, clothing and other necessities to Cambridge soldiers at the front. Reports from army camps included notes from soldiers and officers to “the ladies of the First Universalist Society of Cambridge,”4 “those patriotic ladies of Cambridgeport,”5 and other groups (overwhelmingly women) who supplied turkey and other food items that allowed for a Thanksgiving dinner in the barracks. While Cambridge men could fight and die for the Union, the city’s women made their contributions to the war effort through the personal sacrifice of their brothers, husbands and sons, as well as through the collection and dissemination of provisions for the troops.

Once formal hostilities had ceased, Massachusetts officials looked to the legacy of Thanksgiving as one that could help heal the wounds of war and reconnect the disparate sections of the newly-reunited nation. The Cambridge Chronicle noted in 1865 that “on Thursday, December 7, we shall observe both our State and National Thanksgivings. It is fitting that they should occur on the same day, for will not the States be glad when the nation rejoices?”6 A week later, the Chronicle expressed optimism that an annual national Thanksgiving would do much to promote national unity and gratitude. The author concedes that “[o]ur fellow citizens of the South…feel defeat at the end of their expenditures, and are not yet prepared to rejoice that they were defeated,” but expressed hope that, “as the years roll round, as the soothing influences of time are felt, that an annual National Thanksgiving will become a fixed institution. It will be powerful as a means of breaking down State pride, and sectional hatred….[T]he good old puritanical custom, forcing its way into National observance, shall through its family reunions, and thankful retrospections, do much for the promotion of peace of earth, and good will among men.”7

During the post-Civil-War period, as the work of Reconstruction seemed at first so promising, a national Thanksgiving holiday with its traditions firmly rooted in the Pilgrim legacy became a symbol of the triumph of American values over sectional divisions. Through their embracing of Massachusetts as the birthplace of this uniquely American holiday, Cantabrigians – whether at home or away at war – were able to appropriate the myth of their Pilgrim ancestors as a means of centering New England in not only the Thanksgiving story but also in the dominant narrative of the American founding.

Footnotes:

- Cambridge Chronicle, November 10, 1860.

- Ibid.

- Cambridge Chronicle, November 16, 1861.

- Cambridge Chronicle, November 30, 1861.

- Cambridge Chronicle, December 7, 1861.

- Cambridge Chronicle, December 2, 1865.

- Cambridge Chronicle, December 9, 1865.